Atlas Shrugged, part I, chapter V

Although the most vivid (and creepiest) scenes depicting Ayn Rand’s views on love and sex are still to come, this chapter offers a preview, as we find out in flashback that Dagny and Francisco became lovers during their college days. The first hint of this comes on a summer day when they’re walking along the Palisades. Here’s how Francisco initiates their relationship:

He said brusquely, “Let’s see if we can see New York,” and jerked her by the arm to the edge of the cliff. She thought that he did not notice that he twisted her arm in a peculiar way, holding it down along the length of his side; it made her stand pressed against him, and she felt the warmth of the sun in the skin of his legs against hers. [p.95]

Time out! This is extremely (and unfortunately) apropos, since just this week, the issue of sexual harassment in the skeptical community boiled over with the public naming of some alleged offenders. Francisco’s treatment of Dagny here is textbook sexual assault. Rather than asking, he seizes her to force her to go where he wants and twists her arm to press her body against his. The text treats this as a sweetly innocent moment, although in reality I think most people – especially in a dangerous environment like a high cliff! – would be creeped out and terrified.

Let’s pause for a digression that will momentarily prove relevant: One of the keystones of Ayn Rand’s philosophy is her supposed belief about “initiation of force” and why it’s always wrong. You see, her argument is that real capitalists are peaceful people who trade with each other by mutual consent, whereas it’s only evil looters and socialists who use guns to compel others to do their bidding (for example, by forcing them to pay taxes). It’s supposed to be a core principle of Rand’s philosophy that violence of any kind is only permissible in self-defense, and that initiation of force is immoral, always.

OK, got that? Now let’s see what comes next.

After Francisco’s speech about the “code of competence“, Dagny says that she agrees with him but asks, “Francisco, why are you and I the only ones who seem to know it?” Francisco asks her why she cares about anyone else’s opinion, and she responds:

“Well, I’ve always been unpopular in school and it didn’t bother me, but now I’ve discovered the reason… They dislike me, not because I do things badly, but because I do them well. They dislike me because I’ve always had the best grades in class. I don’t even have to study. I always get A’s. Do you suppose I should try to get D’s for a change and become the most popular girl in school?”

Francisco stopped, looked at her and slapped her face. [p.98]

This isn’t a gentle swat: Francisco hits her hard. We’re specifically told that Dagny tastes “blood in the corner of her mouth” and, even more appallingly, “braced her feet to stop the dizziness” [p.99]. How hard would you have to slap someone for them to be dizzied by the blow and almost fall down?

There’s no possible way you can invoke self-defense here. Dagny wasn’t threatening Francisco’s life or property (obviously); she made a joke that he didn’t like, about concealing her talent to better fit in with average people. And he felt that an appropriate response to this was to hit her as hard as he could. There’s no hint in the text that Rand finds anything wrong with this; Dagny isn’t even mad at him for it. In fact, she says, in an “insolently casual” tone, “I hope it swells terribly. I like it.”

Remember this scene later on, when Rand’s capitalists are giving grand defiant speeches about how they’re the moral ones, the ones who are blameless of initiating force. In contradiction to what she says elsewhere, Rand clearly does think that unprovoked violence is at least sometimes acceptable. More specifically, what she seems to think is that it’s OK to commit violence against people who don’t worship unfettered capitalism as much as she does, who believe that competition isn’t everything or that the government sometimes has a role to play. (This has come up before, and will come up again later.)

And if Francisco’s twisting of her arm is textbook sexual assault, Dagny’s self-justifying excuse for why she doesn’t tell anyone about it bears a very unfortunate resemblance to the battered wife’s rationalization of “he’s not really a bad person, you wouldn’t understand”:

When she came home, she told her mother that she had cut her lip by falling against a rock. It was the only lie she ever told. She did not do it to protect Francisco; she did it because she felt, for some reason which she could not define, that the incident was a secret too precious to share. [p.99]

Last but definitely not least, there’s a scene a few pages later where they have sex (in a clearing in the woods) for the first time. This is how it’s portrayed:

He held her, pressing the length of his body against hers with a tense, purposeful insistence, his hand moving over her breasts as if he were learning a proprietor’s intimacy with her body, a shocking intimacy that needed no consent from her, no permission.

…She knew that fear was useless, that he would do what he wished, that the decision was his, that he left nothing possible to her except the thing she wanted most – to submit. [p.105]

OK, there is such a thing as nonverbal consent, and this scene is written so that Dagny is silently thinking (although not saying) that this is what she wanted all along. Still, it avoids being rape only on that technicality. The text goes out of its way to imply that if she hadn’t consented, it wouldn’t have mattered because he would have done what he wanted anyway. It’s extremely creepy the way Rand repeatedly emphasizes that he doesn’t ask her permission and doesn’t act as if he needs to ask. And remember, again, that Francisco is one of the heroes we’re meant to emulate (you can tell because he has super-Mary Sue powers).

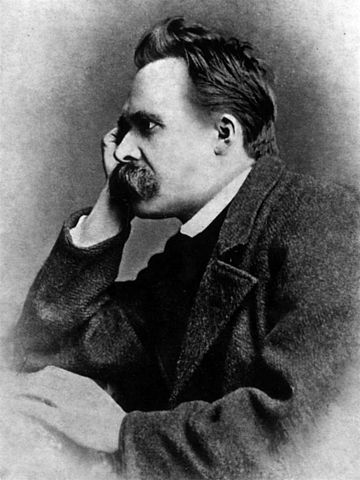

Although the only philosopher whom Rand acknowledged as an influence was Aristotle (all the rest of her ideas, she claimed, came from her own head without outside influence), these scenes show that this is a lie. She was strongly influenced by others: in particular, by Nietzsche and his idea of the heroic “ubermensch” who will shatter all slave moralities based on compassion and reinvent the world in his own image. Francisco is Nietzsche’s ubermensch incarnated: the man who can do whatever he wants – hit people who displease him, twist women’s arms, force them to have sex with him – because he’s a superior being who’s advanced beyond lesser men’s pitiful standards of good and evil.

The Rand-Nietzsche connection has been noticed before: Whittaker Chambers pointed it out in 1957 in National Review, and even one of Rand’s cousins teased her about it, saying that Nietzsche “beat you to all your ideas”. But regardless of where the inspiration came from, we still ought to find it disturbing. Is Francisco’s violent, possessive, entitled behavior something that should be taken as characteristic of the ideal man?

Image credit: Wikimedia Commons

Other posts in this series: