Atlas Shrugged, part I, chapter VIII

“Well, it’s like this, Miss Taggart,” said the delegate of the Union of Locomotive Engineers. “I don’t think we’re going to allow you to run that train.”

Dagny sat at her battered desk, against the blotched wall of her office. She said, without moving, “Get out of here.” [p.216]

Yes, this chapter deals with Rand’s views on the proper relations between labor and management. Strap yourselves in, folks, it’s going to be a fun ride.

The thing you need to keep in mind, the thing that shapes Ayn Rand’s entire view toward unions and the labor movement, is that she thinks work is its own reward and that business success counts for more than anything, including the health of the people who made it possible. (She says so explicitly in this chapter: “the sight of an achievement is the greatest gift a human being could offer to others” [p.222]).

As we saw in the chapter on Hank Rearden, the World’s Worst Boss, Rand doesn’t think that sickness, tiredness or pain are reasons not to work. It follows that she finds labor agitation incomprehensible. In her eyes, the only reason that union members might threaten to strike is because they’re evil, anti-life moochers who hate capitalism. (Rand’s lifelong favorite book was an anti-union novel called Calumet K, which you can read online if you like.)

But back to Dagny’s office. The union representative is still haranguing her:

“What you’re doing is a violation of human rights. You can’t force men to go out to get killed – when that bridge collapses – just to make money for you.”

She searched for a sheet of blank paper and handed it to him. “Put it down in writing,” she said, “and we’ll sign a contract to that effect.”

“What contract?”

“That no member of your union will ever be employed to run an engine on the John Galt Line.” [p.217]

Predictably, the evil union official hems and haws at this. Dagny sneers at him: “You want me to provide the jobs, and you want to make it impossible for me to have any jobs to provide.”

Rand treats this as if her heroine has caught the greedy union thug in an irreconcilable contradiction, but the resolution is obvious, and even the text states it: unions want jobs for their members, yes, but they also want safe jobs that won’t kill or maim the people who do them.

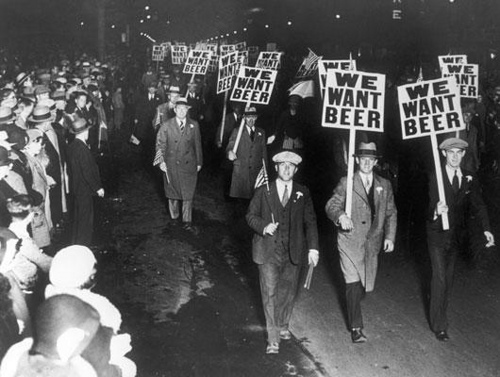

In the days before unions, fatal work accidents were commonplace – employers reasoning that it was cheaper to replace injured or dead workers than to spend money improving safety. The most infamous example was the 1911 Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire, where 146 garment workers either burned to death or leaped from windows to their doom upon finding that managers had locked the building’s exits.

Unions came about in part to change this calculus and to persuade management that the human beings who worked for them weren’t a replaceable commodity. And where the labor movement isn’t strong, preventable on-the-job deaths and illnesses are still happening – like the deadly factory collapse of Bangladesh’s Rana Plaza, or agricultural workers sprayed with toxic pesticides. Rand, of course, never even pays this history a passing glance.

“That train is going to be run. You have no choice about that. But you can choose whether it’s going to be run by one of your men or not. If you choose not to let them, the train will still run, if I have to drive the engine myself… If you think that I need your men more than they need me, choose accordingly. If you know that I can run an engine, but they can’t build a railroad, choose according to that.”

Remember, Rand’s protagonists are omnicompetent super-geniuses who can do anything, so other people desperately need them, but they don’t need anyone. Small wonder that, in the world of this book, the relationship between labor and management is so one-sided.

But in the real world, as it turns out, most people don’t possess every conceivable skill. Despite what Rand seems to think, just because you run a railroad doesn’t mean you can perform any job at that railroad, from driving the spikes to building the engines. Except for the simplest kinds of manual labor, most employable skills require some degree of specialization. That’s why large numbers of people have to cooperate to make almost any kind of business work. Ayn Rand is loath to admit this, as you might expect.

In the end, the conflict is averted when Dagny puts out a call for volunteers, which in true Hollywood-cliche fashion gets an overwhelming response:

The anteroom of the office was full. Men stood jammed among the desks, against the walls. As she entered, they took their hats off in sudden silence. She saw the graying heads, the muscular shoulders, she saw the smiling faces of her staff at their desks… [p.218]

The real Taggart employees wouldn’t even think of joining a strike, because they know that Dagny is entirely benevolent and would never put them in danger either out of indifference or misjudgment. All they need is the assurance of their Glorious Corporate Leader to rush headlong into a potentially dangerous situation, because in Rand’s world, trusting your boss when they tell you it’s perfectly safe means you’ll always come out unscathed. It’s hard to imagine that even the most ardent Objectivist would argue that this lesson carries over into the real world.

Image credit: Tony Werman, via CC BY 2.0 license

Other posts in this series: