Atlas Shrugged: Part 1, The Movie

The question of why Atlas bombed at the box office is really two questions. One is why it didn’t get more attention from the conservatives who’d seem to be its natural audience; the other is why it didn’t attract more interest from moviegoers in general. Let’s start with the first question.

The problem I see is that Rand set potential filmmakers an impossible task: her heroes and villains have to be distinguishable at a glance. The protagonists have jutting chins and sharp, virtuous cheekbones; the bad guys have gangly, floppy limbs and jowls of evil. In the scene at Hank’s party, she went so far as to say that a Randian hero stands out from a crowd of moochers like the Ascent of Man striding from primordial ooze. No real-human-being casting could depict this accurately, but it seems like the filmmakers didn’t even try, which is sure to weaken the film in the eyes of the faithful.

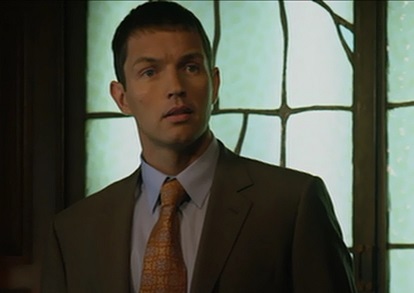

First of all, there’s Ellis Wyatt. We see him on TV in one of the first scenes of the movie, and then again when he comes to bluster and bully Dagny about the Rio Norte Line. This is how the movie depicts him:

This is just wrong, clearly. This Ellis Wyatt is a rotund man with a big belly, and as we all know, the circle is the most socialist of shapes. Didn’t the screenwriters consult the book? Randian heroes aren’t supposed to be short and stout. Ellis Wyatt is supposed to be rangy, grizzled, dangerous-looking; I always pictured him as Sam Elliott or John Hurt. But no matter who plays him, at the very least he should have a Yosemite Sam mustache.

Then there’s the Taggart siblings, Dagny and James:

With Dagny, at least the filmmakers were thinking along the right lines. But I’m not convinced Taylor Schilling has the gravitas to pull it off. Dagny is supposed to be the Iron Lady, radiating inhuman sternness and competence, but Schilling plays her, basically, as a generic MBA-from-Wharton blonde executive. Those slightly pursed lips are the closest thing to stone-cold determination she ever projects.

Granted, this may be a defect of the writing, not of the actor. It’s probably impossible for a human being to portray Dagny, or any Randian protagonist, the way they’re meant to come off. Even a libertarian critic noted this, saying that Dagny “seemed too much like a normal human being for a Randian romantic heroine”. In the world of Atlas, being a normal human being isn’t a compliment.

Meanwhile, they made the opposite error with James Taggart. Jim is supposed to be a fleshy, sweaty man who erupts into a shrill panic whenever anything doesn’t go his way, trying to evade the realization that his world is imploding around him. Instead, the film casts him as mildly sleazy and shallow at best, like a slacker frat boy who inherited his dad’s business and is in over his head. Rather than gloating, cowardly evil, his most serious reaction to any setback is a slack-jawed “Dude, not cool!” expression.

Dude! You were totally supposed to bring the keg for the rager at Sig Ep tonight!

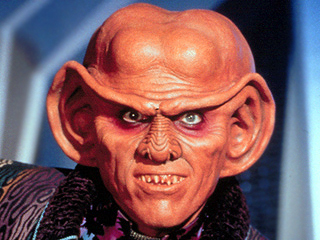

Not all the casting is terrible. Grant Bowler, who plays Hank Rearden, pulls off the empty-Armani-suit look about as well as could be expected (although I always pictured Alec Baldwin as Hank), while Michael Lerner does a decent generically evil bureaucrat with Rearden’s turncoat lobbyist Wesley Mouch. There’s also a minor part by Armin Shimerman, best known for his role as Quark the Ferengi from Star Trek – a deceitful, amoral schemer motivated only by profit, or in other words, a perfect Randian hero.

They also treat women as property, which Ayn Rand wouldn’t have been OK with. Probably.

Last but not least, there’s Dagny’s loyal right-hand man Eddie Willers. This casting, at least, shouldn’t be difficult to fill. Since Eddie is an ordinary schmoe, not a Nietzschean superman like the main characters, he should be much easier to get right. And then the filmmakers had to go and do this:

Yes, they made Eddie black. This may have been well-intentioned, possibly an attempt to add some diversity to the monochrome cast of the book; but instead, the filmmakers managed to conjure up an even worse cliche. Then again, it may not have been entirely a coincidence. Can it really be an accident that the only major sympathetic character whose race they’d dare to change is also the only one who suffers a tragic fate in the end?

Other posts in this series: