Atlas Shrugged, part II, chapter II

Atlas Shrugged, part II, chapter II

Let me make one thing clear, to begin with: I don’t think Ayn Rand was an unintelligent person. She was fiercely dogmatic in her opinions, quick to anger, possessed an enormous ego, and rarely if ever forgave. She also had more than a few intellectual blind spots, which I’ve been pointing out throughout this series. But I believe she put real thought into her moral system, flawed as it is, and had a genuine desire to be taken seriously as a philosopher.

I say all this as a prelude to today’s post, in which Rand manages to write one of the most fantastically stupid sentences I’ve ever seen committed to paper. It comes right at the end of Francisco’s wedding-speech filibuster. And here it is:

“When you have made evil the means of survival, do not expect men to remain good. Do not expect them to stay moral and lose their lives for the purpose of becoming the fodder of the immoral. Do not expect them to produce, when production is punished and looting rewarded. Do not ask, ‘Who is destroying the world?’ You are.

…Throughout men’s history, money was always seized by looters of one brand or another, whose names changed, but whose method remained the same: to seize wealth by force and to keep the producers bound, demeaned, defamed, deprived of honor. That phrase about the evil of money, which you mouth with such righteous recklessness, comes from a time when wealth was produced by the labor of slaves – slaves who repeated the motions once discovered by somebody’s mind and left unimproved for centuries. So long as production was ruled by force, and wealth was obtained by conquest, there was little to conquer. Yet through all the centuries of stagnation and starvation, men exalted the looters, as aristocrats of the sword, as aristocrats of birth, as aristocrats of the bureau, and despised the producers, as slaves, as traders, as shopkeepers – as industrialists.

To the glory of mankind, there was, for the first and only time in history, a country of money – and I have no higher, more reverent tribute to pay to America, for this means: a country of reason, justice, freedom, production, achievement. For the first time, man’s mind and money were set free, and there were no fortunes-by-conquest, but only fortunes-by-work, and instead of swordsmen and slaves, there appeared the real maker of wealth, the greatest worker, the highest type of human being – the self-made man – the American industrialist.”

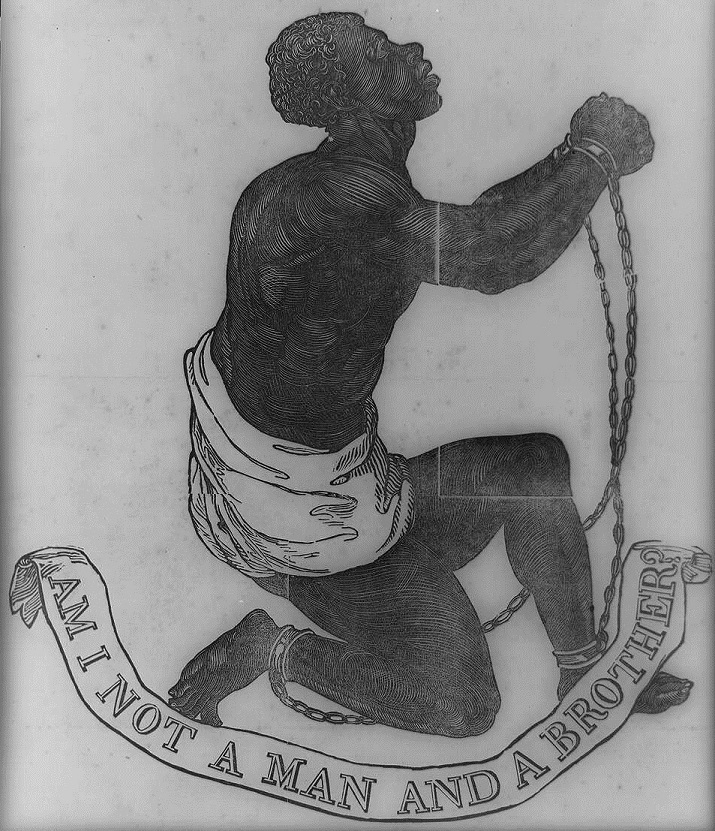

No fortunes by conquest in America? No slave labor in America? Really?

I have to ask: Did Ayn Rand ever read the Constitution of the country whose praises she sings? Because if she had, she might have noticed that Article 1, Section 2 says this:

Representatives and direct Taxes shall be apportioned among the several States which may be included within this Union, according to their respective Numbers, which shall be determined by adding to the whole Number of free Persons, including those bound to Service for a Term of Years, and excluding Indians not taxed, three fifths of all other Persons.

That phrase “all other Persons” is a vague catch-all, thrown like a sheet over an ugly reality: America was founded as a nation of slavery. It’s true that the industrialists and inventors came along later – although I suspect the claim that America was the first time and place they ever existed is debatable at best – but they weren’t there from the beginning. Before the cotton gin, before the electric light bulb, before the Wright brothers, before the Model T, there were the plantations and the enslaved people who labored on them: millions of people who could be sold and traded like cargo, who could be raped, brutalized or killed at a whim, who labored all their lives to make their owners rich and got nothing for it, and who were counted as less than fully human by their own government.

Slavery wasn’t a minor peccadillo, an insignificant footnote to Francisco’s peroration. It was the major source of wealth in the country’s first few decades: in the first half of the 19th century, the total market value of human beings held in bondage was greater than all the country’s banks, factories and railroads combined. On the eve of the Civil War, slaves were about 16% of all the wealth in the country. In today’s dollars, that would be $10 trillion.

Slavery was America’s original sin, and it took a bloody, brutal war to abolish it; and even with that, its poisonous effects still linger on. If you want to argue, as Abraham Lincoln did, that America paid a high price to expiate that crime and that we now know better, so be it. But it’s an insult to our national memory to gloss it over, to pretend that it never existed. There were “fortunes by conquest” in America – the native people who were displaced from the land; the enslaved people who were set to work that land – and much of our early wealth, perhaps much of our modern wealth, can be traced back to that.

Of course, it would throw a wrench into Rand’s history-as-morality-play sermon to admit that America was a major source of the slavery she so despised. But that’s not an excuse; it’s just a further illustration of how the real world contains more than she dreamt of in her philosophy, and refuses to conform to the simplistic scheme of bright whites and dark blacks that she sets out for it.

Image: An anti-slavery woodcut, originally created by the Society for the Abolition of Slavery in England, adapted by the American Anti-Slavery Society for John Greenleaf Whittier’s 1837 poem “Our Countrymen in Chains“; image via Library of Congress

Other posts in this series: