Atlas Shrugged, part II, chapter III

When she hears that Hank Rearden and Ken Danagger have been indicted for illegally doing business, Dagny rushes to Pittsburgh. For reasons she can’t fully explain, she’s certain that Danagger will be the next to vanish, and she’s desperate to reach him and convince him to stay before he’s taken away by the “destroyer” – her term for whatever force or entity is causing all the country’s great capitalists to disappear without a trace.

Her appointment with Danagger is at 3:00, but at 3:30, she’s still waiting in the lobby while he talks to someone else in his office. His secretary apologizes at length, saying that her boss is extremely punctual usually (“Ken Danagger was as rigidly exact about his schedule as a railroad timetable… he had been known to cancel an interview if a caller permitted himself to arrive five minutes late” – because of course a savvy businessman throws a multimillion-dollar contract in the garbage if their customer gets stuck in traffic).

Dagny sits and chain-smokes, becoming more and more impatient the longer Danagger spends with his mysterious visitor:

The door was not locked, thought Dagny; she felt an unreasoning desire to tear it open and walk in… but she looked away, knowing that the power of a civilized order and of Ken Danagger’s right was more impregnable a barrier than any lock.

Just to be clear, this is the same Dagny Taggart who threatened to murder any government official who made her apply for a permit; who bribed judges and legislators to let her seize a plant that went bankrupt; and who, yes, walked into an unguarded factory and carried out a piece of valuable machinery, with no idea whether there was a legal owner or not. (Thanks to arensb for pointing that last one out.) Randian protagonists’ regard for “civilized order” seems to be highly selective.

Dagny asked slowly, as a demand, in defiance of office etiquette, “Who is with Mr. Danagger?”

“I don’t know, Miss Taggart. I have never seen the gentleman before.” She noticed the sudden, fixed stillness of Dagny’s eyes and added, “I think it’s a childhood friend of Mr. Danagger… He came in unannounced and asked to see Mr. Danagger and said that this was an appointment which Mr. Danagger had made with him forty years ago.”

“How old is Mr. Danagger?”

“Fifty-two,” said the secretary. She added reflectively, in the tone of a casual remark, “Mr. Danagger started working at the age of twelve.”

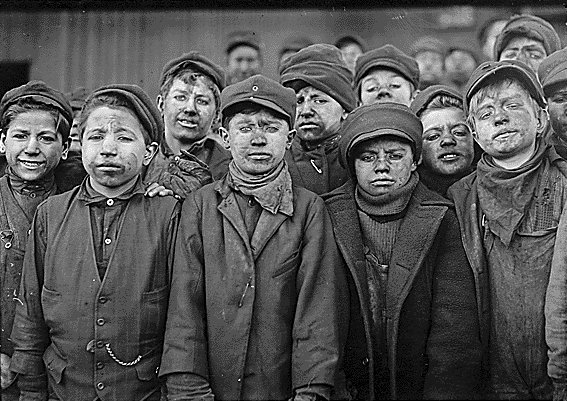

This double-take-worthy sentence is said so casually, it’s easy to breeze past it. But Danagger works in the coal industry, remember! We must be meant to conclude that he started working in a coal mine at the age of twelve. (Thus beating Hank Rearden’s child-labor record by two years.)

Although the Western world has largely eliminated child labor, it still exists, and needless to say it’s not the path to fame and fortune that Atlas imagines. In countries like Ivory Coast and Burkina Faso, child laborers work in the fields in conditions scarcely distinguishable from slavery, picking cotton or cacao. Chinese factories have repeatedly been caught using underage laborers as well.

The industries that exploit child labor today do so for the same reasons as the industries of yesteryear. Historically, child labor was used for dangerous work like glassmaking, in mills and canneries, both because owners could pay child workers less and because they were considered less likely to protest backbreaking toil or hazardous working conditions. And yes, there really once were child coal miners.

Child labor is both a cause and a consequence of poverty. Without a social safety net, desperate families who can’t support their children may have no choice but to put them to work; but full-time labor makes it impossible for those children to get an education that could lead to a better job, thus perpetuating the cycle of poverty. Rand doesn’t take note of this, but only because she’s scripted a world where education is somehow irrelevant. Hank Rearden can drop out after elementary school to labor in a mine, and still become a super-genius, good-at-everything metallurgist-architect-executive – rather than, say, being stuck at a fifth-grade reading level for life. (Francisco d’Anconia may be implausibly competent, but at least he went to college.)

And as in other things, Rand’s followers carry her simplistic ideas over into the real world. Chip Wilson, the founder of the yoga-wear company Lululemon, is an Ayn Rand devotee, and in 2005, he spoke at a sustainability conference to argue for child labor, asserting that 12- and 13-year-olds would be better off working in factories. Maine’s Tea Party governor Paul LePage has also called for the loosening of anti-child-labor laws.

Finally, Dagny is shown into Danagger’s office:

“How do you do, Miss Taggart,” he said. “Forgive me, I think that I have kept you waiting. Please sit down.” He pointed to the chair in front of his desk.

“I didn’t mind waiting,” she said. “I’m grateful that you gave me this appointment. I was extremely anxious to speak to you on a matter of urgent importance.”

…He looked at her in silence, and then he said, “Miss Taggart, this is such a beautiful day — probably the last, this year. There’s a thing I’ve always wanted to do, but never had time for it. Let’s go back to New York together and take one of those excursion boat trips around the island of Manhattan. Let’s take a last look at the greatest city in the world.”

She sat still, trying to hold her eyes fixed in order to stop the office from swaying. This was the Ken Danagger who had never had a personal friend, had never married, had never attended a play or a movie, had never permitted anyone the impertinence of taking his time for any concern but business.

We’re meant to imagine ominous background music as he speaks these sentences. Danagger’s desire to have some leisure for the first time in his entire life, to take a sightseeing trip on a beautiful day, isn’t an outbreak of normal-human-being behavior but proof that he’s become one of the pod people. (The horror, the horror: Randian capitalists are being replaced by sinister duplicates who pay a living wage, treat their employees well and expect them to have a life outside work!)

She presses him about who his visitor was, why he’s retiring, what he intends to do now. He refuses to answer each of her questions:

“What will you do with” — she pointed at the hills beyond the window — “the Danagger Coal Company? To whom are you leaving it?”

…”Want me to leave it all to you?” He reached for a sheet of paper. “I’ll write a letter naming you sole heiress right now, if you want me to.”

She shook her head in an involuntary recoil of horror. “I’m not a looter!”

Say what now? Why would it be “looting” for Dagny to accept a lawful transfer of private property? And, again, if it would be wrong to take someone else’s property without compensation, then how do we explain her blithely removing the magic motor from the factory where she found it, without any idea who the legal owner was?

Image: Child laborers in a coal mine, circa 1910. Credit: Wikimedia Commons, original photo by Lewis Hine

Other posts in this series: