Atlas Shrugged, part II, chapter VI

The villains are debating the membership of the Unification Board, the new government agency that will control every aspect of America’s economy under Directive 10-289. The first proposal is for them to choose a representative of each industry and profession; but then Fred Kinnan, the union leader, steps in.

“No cross-sections,” said Fred Kinnan evenly. “Just representatives of labor. Period.”

“What the hell!” yelled Orren Boyle. “That’s stacking the cards, isn’t it?”

“Sure,” said Fred Kinnan.

“But that will give you a stranglehold on every business in the country!”

“What do you think I’m after?”

Kinnan says that “[his] boys” won’t like the first point of Directive 10-289 – that all workers will be assigned to jobs by government decree, and no one will be allowed to retire or quit – but if he gets to run the Board, he’ll get them to accept it. The rest of them complain that this is unfair and the country won’t stand for it, but he scoffs:

“Stop kidding yourself,” said Kinnan. “The country? If there aren’t any principles any more — and I guess the doc is right, because there sure aren’t — if there aren’t any rules to this game and it’s only a question of who robs whom — then I’ve got more votes than the bunch of you, there are more workers than employers, and don’t you forget it, boys!”

Rand portrays this as a blatant power grab: because Kinnan commands more votes than the corrupt industrialists and politicians, he can run roughshod over them. But this is hardly sinister; it’s just democracy in action. In most circumstances, the will of the majority prevails. That seems like a perfectly workable principle to me.

Atlas‘ vision of utopia is a world where a tiny minority of ultra-wealthy property owners control everything. The idea that ordinary people should have a vote in how society is run, as we see here, is something that Rand considers a dirty trick, a dangerous notion akin to anarchy. And if you think about it, you’ll see why it’s so threatening to her philosophy.

Even Rearden Steel and Taggart Transcontinental have more workers than employers. No matter how hypercompetent they are, Hank and Dagny can’t pour every mold, flip every switch, stoke every furnace, or drive every engine. In other words, and contrary to what Rand argues elsewhere, it’s not just the one-percenters who keep the world moving. They need the help and cooperation of large numbers of people to succeed, whether they like to admit it or not. The idea that they could be forced to admit that dependence, such as if their workers voted to strike, is something the Objectivist philosophy finds intolerable to contemplate, so it has to be depicted as a monstrous affront to morality.

“Okay,” said Kinnan amiably, “let’s talk your lingo. Who is the public? If you go by quality — then it ain’t you, Jim, and it ain’t Orren Boyle. If you go by quantity — then it sure is me, because quantity is what I’ve got behind me.” His smile disappeared, and with a sudden, bitter look of weariness he added, “Only I’m not going to say that I’m working for the welfare of my public, because I know I’m not. I know that I’m delivering the poor bastards into slavery, and that’s all there is to it. And they know it, too. But they know that I’ll have to throw them a crumb once in a while, if I want to keep my racket, while with the rest of you they wouldn’t have a chance in hell. So that’s why, if they’ve got to be under a whip, they’d rather I held it, not you — you drooling, tear-jerking, mealy-mouthed bastards of the public welfare!”

…He stood up. No one answered him. He let his eyes move slowly from face to face and stop on Wesley Mouch.

“Do I get the Board, Wesley?” he asked casually.

“The selection of the specific personnel is only a technical detail,” said Mouch pleasantly. “Suppose we discuss it later, you and I?”

Everybody in the room knew that this meant the answer Yes.

Now this is puzzling. It seems Rand wants to convey that Kinnan, alone of all the villains, has a tiny spark of decency. He says that the whole idea of Directive 10-289 “makes [him] sick” – he knows he’s delivering his workers into slavery, and he hates that idea. He also knows this plan will result in the collapse of society, but even though he’s powerless to change that outcome, he’s determined to help his people out for as long as he can.

But wait – why can’t he change that outcome? We were just told that he can persuade his unions to accept Directive 10-289, so presumably he could do the opposite. If he wanted to put the kibosh on this plan, he could denounce it and call for a nationwide strike, and from all textual indications, he’d win. So why doesn’t he? What does he get out of going along with this rather than fighting it?

In this book, the answer is that “he’s evil”, and the evil of a Randian villain never needs to be explained. But in real life, where people aren’t motivated by sourceless, causeless malevolence, labor unions have often been an effective force resisting tyranny and repression.

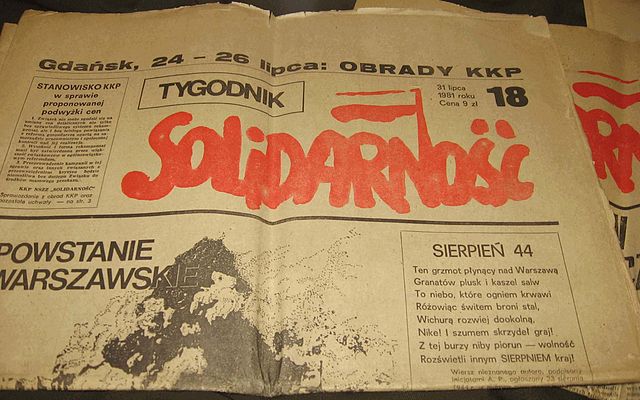

The crowning historical example of this is Solidarity, the Polish labor union that arguably brought down communism. In the 1980s, when Poland was a Soviet satellite under the Warsaw Pact, Solidarity was founded at a Gdansk shipyard by the activist Lech Walesa and other current and former workers. They called for a strike in response to the firing of workers who attempted to organize, as well as to protest government policies that froze wages, raised prices, and resulted in chronic shortages in the heavily indebted, state-run economy.

But Solidarity wasn’t just a workers-rights movement. It set its goals higher, demanding an end to state censorship, freedom for political prisoners, and the firing of government officials who took bribes or used force. And it caught on like wildfire, spreading across Poland in spite of all attempts to stop it, with workers occupying and shutting down shipyards, mines and factories.

The Communist government initially responded with martial law and repression. In some instances, soldiers fired on strikers, killing some. But while they were able to force Solidarity underground, they weren’t able to crush it. Eventually, as the glasnost era dawned under Gorbachev, Solidarity forced the government to the bargaining table and won the right to run candidates in the 1989 election, where they won a massive landslide. Although these elections weren’t fully free, this shocking result weakened the government’s grip and paved the way for the anti-communist revolutions across eastern Europe later that year, culminating in Poland’s peaceful transition to democracy. For his pivotal role, Walesa himself won the Nobel Peace Prize.

The idea of socialism fighting communism is something Ayn Rand probably would have found impossible to understand. As I previously mentioned, she believed that there were only two sides – Mine and Everybody Else – and that everyone who wasn’t of her faction must therefore have been working together against her. (For example, she despised the fledgling Libertarian Party, for all that you might think they’d be natural allies; the problem, in her eyes, was that they used some of her ideas but not all of them.) The reality is that there are a lot more than two opinions in the world, and people can agree on some issues while disagreeing fiercely on others.

Image: The first issue of Tygodnik Solidarność (Polish for “Solidarity Weekly”), a newspaper published in Communist Poland by the Solidarity union in April 1981; via Wikimedia Commons

Other posts in this series: