Atlas Shrugged, part II, chapter VII

Hank Rearden asks Ragnar Danneskjold, the pirate, why he’s chosen a life of violence against society, rather than just disappearing like the vanished industrialists:

The shock that came next was to see Danneskjold smile: it was like seeing the first green of spring on the sculptured planes of an iceberg. Rearden realized suddenly, for the first time, that Danneskjold’s face was more than handsome, that it had the startling beauty of physical perfection — the hard, proud features, the scornful mouth of a Viking’s statue…

“…I’ve chosen a special mission of my own. I’m after a man whom I want to destroy. He died many centuries ago, but until the last trace of him is wiped out of men’s minds, we will not have a decent world to live in.”

“What man?”

“Robin Hood.”

Rearden looked at him blankly, not understanding.

“He was the man who robbed the rich and gave to the poor. Well, I’m the man who robs the poor and gives to the rich — or, to be exact, the man who robs the thieving poor and gives back to the productive rich.”

“The thieving poor”. Could any phrase be more telling about Ayn Rand’s worldview?

Rand judges the very existence of the poor to be an act of theft – taking up space and resources that rightfully belong to the rich. For the crime of not being sufficiently “productive”, they deserve to be menaced and robbed by a pirate like Ragnar, who deprives them of what little they have so that their money can be given to those, like Hank, who are already as wealthy as anyone could ever expect or need to be. (I suppose she might be generous and exempt the “good” poor who’d rather go hungry than accept food stamps, if any such people exist, but there’s no doubt that she’d consider the vast majority of actual poor people to be grasping thieves.)

If we were talking about a triage scenario where there were more needy people than we could provide for, that would be one thing. But this story is set in the United States of America, the richest, most technologically advanced and most powerful nation in the history of the world up until now. There’s no doubt that we could easily sustain our entire population in reasonable comfort if we chose to. The fact that we have a very different distribution of wealth isn’t the result of chance, nor is it the “natural” outcome. It’s the intentional result of policy decisions that we’ve made, as surely as if there were real-life Ragnar Danneskjolds stealing from the poor and the needy to give to the wealthy and the powerful.

You might find it a little puzzling that Danneskjold objects to Robin Hood as violently as he does. In most popular tellings, the legend of Robin Hood takes place in a medieval, feudal society, where people genuinely were oppressed by an unaccountable ruler who could take away their property, their liberty or even their lives on a whim. You’d think that Rand would approve of someone who resisted that kind of tyranny. But, as Danneskjold explains, he objects to the story because it’s become an argument for coerced charity:

“This is the horror which Robin Hood immortalized as an ideal of righteousness. It is said that he fought against the looting rulers and returned the loot to those who had been robbed, but that is not the meaning of the legend which has survived. He is remembered, not as a champion of property, but as a champion of need, not as a defender of the robbed, but as a provider of the poor. He is held to be the first man who assumed a halo of virtue by practicing charity with wealth which he did not own, by giving away goods which he had not produced, by making others pay for the luxury of his pity. He is the man who became the symbol of the idea that need, not achievement, is the source of rights, that we don’t have to produce, only to want, that the earned does not belong to us, but the unearned does.

…Until men learn that of all human symbols, Robin Hood is the most immoral and the most contemptible, there will be no justice on earth and no way for mankind to survive.”

The most immoral and contemptible? No one in human history or legend is more evil than Robin Hood? I could probably think of a few other contenders for that title.

If you find this characterization a little unfair, there’s a reason for that. Rand believed that her capitalism-versus-socialism framework, on a national scale, completely explained the Cold War and the ideological struggle of 20th-century superpowers. That’s a grandiose enough claim in its own right, but she went much further than that: She asserted that her philosophy explains all human behavior in every society throughout history. Every political contest, every power struggle, every clash between opposing factions is ultimately just another instance of the eternal conflict between Noble Capitalists and Evil Looters. The moral evaluation is already made for you; all you have to do is go down the roll call of history and slot everyone into one side or the other, typically by cherry-picking one element of their life that seems relevant to Objectivism in some way.

This inflexible, black-and-white reading of history leads to some odd results. For example, Rand venerated Aristotle and hated Plato, even though Aristotle believed that some people were born to be slaves. You’d think that would be a heinous offense against Objectivism. But in the postscript of Atlas Shrugged, Rand says that although she disagrees with Aristotle about some things, “his definition of the laws of logic… is so great an achievement that his errors are irrelevant by comparison”. Supporting hereditary slavery is irrelevant – a trivial faux pas – by comparison with his great accomplishment of figuring out that A equals A.

Rand squeezes the story of Robin Hood into that same Procrustean framework. While in principle she’s opposed to feudalism, she only approves of people resisting it if they’re driven by the right ideology. And in the story, Robin Hood was motivated by pity – the worst of all possible motivations in a Randian’s eyes. (If he and his Merry Men had instead retreated to Sherwood Forest to live in isolation from the outside world and, I don’t know, mine coal, I assume she’d have loudly cheered them. I wonder what she would think of the Robin Hood Foundation, an anti-poverty charity which counts some of the world’s richest people among its supporters.)

Conversely, the rulers that Robin Hood plundered were motivated by selfishness and greed, which is something that Rand can at least sympathize with. Given the assumptions she starts with, it’s no surprise that Ragnar Danneskjold ends up siding with the Sheriff of Nottingham.

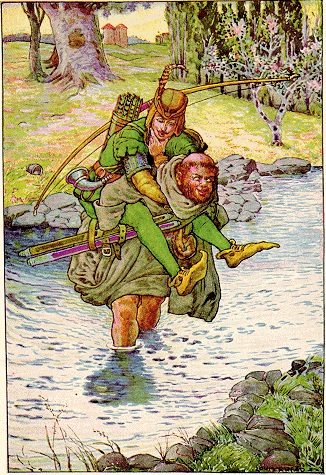

Image: Further evidence that Robin Hood is a moocher who expects others to carry him around. Via Wikimedia Commons

Other posts in this series: