Atlas Shrugged, part II, chapter X

The tramp on Dagny’s train reveals how the mysterious meme “Who is John Galt?” came into being, and why he fears he might have been the one who started it:

“Well, there was something that happened at that plant where I worked for twenty years. It was when the old man died and his heirs took over. There were three of them, two sons and a daughter, and they brought a new plan to run the factory. They let us vote on it, too, and everybody — almost everybody — voted for it. We didn’t know. We thought it was good. No, that’s not true, either. We thought that we were supposed to think it was good. The plan was that everybody in the factory would work according to his ability, but would be paid according to his need. We — what’s the matter, ma’am? Why do you look like that?”

“What was the name of the factory?” she asked, her voice barely audible.

“The Twentieth Century Motor Company, ma’am, of Starnesville, Wisconsin.”

As the tramp tells it, everyone voted for the plan despite their misgivings, but its fatal flaw soon became obvious. Since the way to get paid wasn’t by proving you were a good worker, but by listing all your troubles (“like any lousy moocher”), the people who benefited were the ones who were most creative at coming up with new needs to heap on their fellow workers’ shoulders:

“…it turned into a contest among six thousand panhandlers, each claiming that his need was worse than his brother’s. How else could it be done? Do you care to guess what happened, what sort of men kept quiet, feeling shame, and what sort got away with the jackpot?”

What’s worse, he says, this plan not only rewarded need, it punished ability. If anyone was judged to not be producing as much as he could, he was forced to work nights and weekends to make up for it. This gave all the employees an incentive to work slowly and conceal whatever talent they had, since their productivity had no relation to how much they’d be paid. The only ones who thrived were the dishonest ones who weren’t ashamed to do this:

“God help us, ma’am! Do you see what we saw? We saw that we’d been given a law to live by, a moral law, they called it, which punished those who observed it — for observing it. The more you tried to live up to it, the more you suffered; the more you cheated it, the bigger reward you got.”

The company’s fortunes quickly nosedived, and Starnesville sank into poverty and despair, as men turned to drinking, got into fights, and spied on each other to prove who was lying about their needs. They even tried to break up each other’s families and romantic relationships, so that no one would have spouses or relatives that they were obligated to support. Under the corrupting influence of this system, everyone became hostile and sullen, and the best workers left in a steady trickle, “till we had nothing left except the men of need, but none of the men of ability.” Finally, the factory went bankrupt and shut down, which resulted in an economic crash throughout the state.

But if you had any impulse to feel bad for the workers of Starnesville, don’t. In line with Rand’s conviction that evil is always a conscious choice made with full intent, the tramp says that what happened to them was their own fault:

“If men fall for some vicious piece of insanity, when they have no way to make it work and no possible reason to explain their choice — it’s because they have a reason that they do not wish to tell. And we weren’t so innocent either, when we voted for that plan… There wasn’t a man voting for it who didn’t think that under a setup of this kind he’d muscle in on the profits of the men abler than himself… But while he was thinking that he’d get unearned benefits from the men above, he forgot about the men below who’d get unearned benefits, too. He forgot about all his inferiors who’d rush to drain him just as he hoped to drain his superiors… That was our real motive when we voted — that was the truth of it — but we didn’t like to think it, so the less we liked it, the louder we yelled about our love for the common good.”

You may want to brace yourself before reading the next sentence: For the most part, I agree with Ayn Rand’s critique of communism.

True, she presents it in severely exaggerated form – as in her bizarre insistence that no one genuinely cares about the common good or honestly wants to help the less fortunate – and with much florid, overwrought verbiage that I’ve omitted. Nevertheless, it’s true that classic communism can’t solve the tragedy-of-the-commons problem. An economic system that offers no incentive for individual effort will inevitably be overrun by free-riders. That’s the unfortunate truth of human nature, something that Rand grasped perfectly well (making it all the more inexplicable that she proposed a voluntary government that would suffer from exactly the same problem).

What Rand takes for granted – in this chapter and throughout the book – is that a capitalist enterprise, built on self-interest and private property, can’t turn bad in any way comparable to this. But I can think of one.

Many of the towns we see in this book – Starnesville, Marshville, Wyatt Junction – are named after the capitalists who built them. This being the case, it seems likely that they were company towns, a fixture of the 19th and early 20th century economies. The idea is that companies which ran mines, mills, factories or other industries in isolated, rural regions built villages for their workers to live in, complete with housing and general stores to sell food, clothing and other sundries which would otherwise be hard to get.

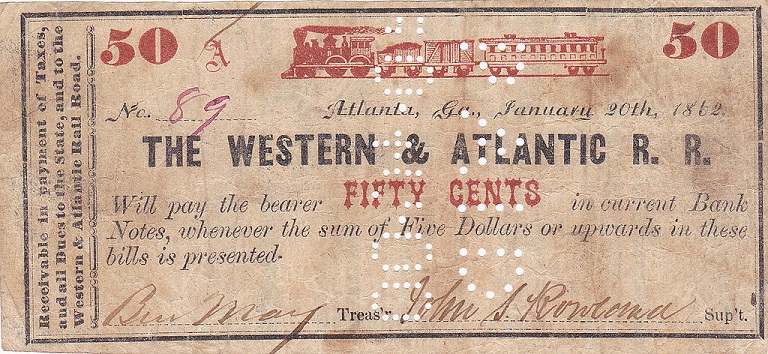

But the snare is that many of them paid workers in scrip, an unofficial currency which was only good at the company store. Workers had no choice but to buy from their own employer, who could gouge them as much as he chose. Often, goods were so overpriced that workers had to borrow against their next payday to buy them, dragging them down into an inescapable spiral of debt (inspiring the classic folk song about the life of a coal miner that gives this post its title). And since scrip couldn’t be spent outside the town and could only be exchanged for cash at extremely unfavorable rates, workers also couldn’t build up savings that would make it easier for them to leave and seek employment elsewhere. Life in these conditions was often little different from slavery.

In addition to company stores, there was also company housing, which the workers and their families had no choice but to live in. Again, since they had no alternative, their bosses could charge extortionate rents; and if they made trouble, police in the company town could arrest or evict labor agitators and other troublemakers for no valid reason. This culminated in the Supreme Court case of Marsh v. Alabama, which held that company towns weren’t First Amendment-free zones. Laws like the British Truck Acts cracked down on the abuses of scrip and company towns, and together with the rise of labor unions like the United Mine Workers, mostly put a stop to it – although even today some companies continue the practice, like Wal-Mart.

Rand envisions capitalism as a free trade between equals and therefore immune from exploitation. The less rosy reality is that capitalism, every bit as much as communism, can be a weapon in the hands of the wealthy and the powerful to trap the poor, the desperate and the disenfranchised in serfdom and coerced servitude.

But after all that, Dagny objects, the tramp hasn’t told her who John Galt is or what he has to do with any of this. He says that it was something that happened at the first all-hands meeting after the company had agreed to go communist:

“‘This is a crucial moment in the history of mankind!’ Gerald Starnes yelled through the noise. ‘Remember that none of us may now leave this place, for each of us belongs to all the others by the moral law which we all accept!’

‘I don’t,’ said one man and stood up. He was one of the young engineers… He stood like a man who knew that he was right. ‘I will put an end to this, once and for all,’ he said… ‘I will stop the motor of the world.’ Then he walked out.

…We never heard what became of him. But years later, when we saw the lights going out, one after another, in the great factories that had stood solid like mountains for generations, when we saw the gates closing and the conveyor belts turning still, when we saw the roads growing empty and the stream of cars draining off… then we began to wonder and to ask questions about him. We began to ask it of one another, those of us who had heard him say it… You see, his name was John Galt.”

If you missed that, John Galt vowed to destroy an entire civilization because one business went communist. Disproportionate retribution seems to be the only kind of retribution that Objectivists know.

This leads back to the question, again, of how the looters came to take over the world. If the Twentieth Century Motor Company’s plan was such a failure, its competitors should have thrived, and once it went bankrupt, the whole idea should have been discarded as an object lesson in what not to do. Instead, for some reason, everyone copied this manifestly disastrous idea, and it spread to all of society despite bringing ruin to everyone who adopted it. Atlas has no real explanation for how this happened, but this hints at an alternative theory that Rand probably didn’t intend: Is it possible that John Galt’s draining the talent from society, and the economic damage this inflicted, is what caused the turn to socialism in the first place?

Image: Western & Atlantic Railroad scrip from 1862. Note the cash exchange rate. Image by Paul Dietrich; released under CC BY-SA 3.0 license, via Wikimedia Commons.

Other posts in this series: