Atlas Shrugged Part II: The Strike

In most things, the producers of Atlas Shrugged Part II were unwilling to deviate in the slightest from the book. They followed the text as slavishly as possible, keeping everything that screen-time and budget constraints would allow. But there are a few places where they chose to make changes, one of which was the climactic train-disaster scene of Part II. It’s illuminating to look at the reasons why, and to see what the changes show – or fail to show – about the filmmakers’ grasp of Ayn Rand’s ideas.

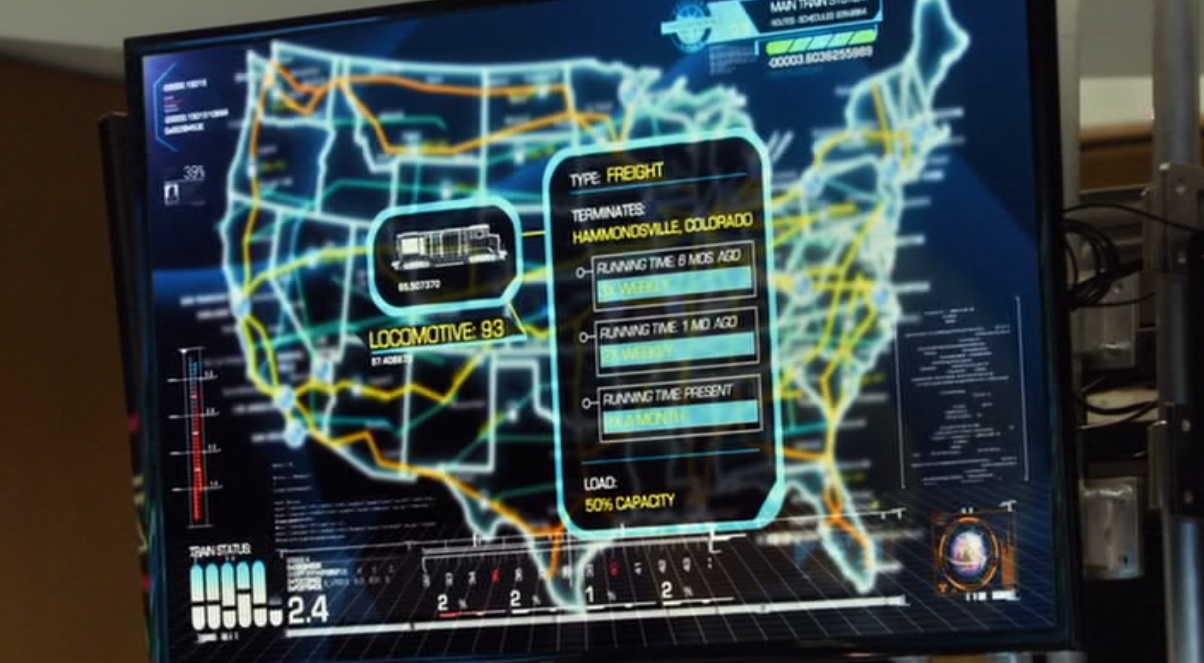

One of the most obvious changes is the creep of technological progress. In the vaguely 1940s-ish setting of Atlas Shrugged the novel, communication is by phone and telegram, TV is only just beginning to come into its own, and computers are non-existent. Of course, given that the filmmakers intended this movie as a parable for our era, they had to bring at least some things up to date or else look ridiculous. Thus, in the movie, Taggart headquarters has all the latest bells and whistles – giant computerized displays that show the position and speed of every train in the country in brilliant, blinking, beeping digital clarity.

This serves the dramatic purpose of showing when the two trains are about to collide so that everyone can look on helplessly, which is a fine way of generating tension. That said, it also heightens the strange contrast of a modern, information-age society that’s critically dependent on railroads and steel mills to power its economy. (Personally, if I were adapting Atlas for the screen, I would’ve made it a period piece, maybe set in an alternate post-WW2 history. The plot makes at least somewhat more sense in the world it came from.)

More interesting are the changes they made to minor characters, especially Dave Mitchum, the incompetent division superintendent who’s responsible for the tunnel disaster. In the book, he’s an older man, late middle-aged at least (the text doesn’t state his age, but it does say that “Seniority of service was his favorite topic” and that “he had been in the railroad business longer than many men who had advanced beyond him”). Yet the movie makes him a fresh-faced junior executive who works in the New York headquarters:

While this change seems merely pointless, there’s one other big difference in Mitchum’s character, one that makes me question whether the filmmakers fully understood the material they were adapting.

In the book, everyone working for the railroad knows that sending a train with a coal-burning engine into the tunnel means certain death for the passengers. But no one wants to admit it, because the first person to speak up and point this out would be blamed for stopping the train. Thus, there’s a frantic scuffle to avoid taking responsibility, as everyone tries to pass the buck to someone else.

In the movie, however, all the dispatchers seem to be dedicated to their job and are working together as a team to get the train safely through the tunnel. And the script implies that they had a real chance, except that one of the passengers panics and hits the emergency brake. Even then, movie-Mitchum tries to save the day by switching the other, oncoming train to another track, but is foiled by a jammed switch. From there, events progress as in the book, except that as the catastrophe plays out, all the Taggart employees seem truly stunned and horrified:

While this is a completely natural and understandable human reaction, it flatly contradicts Rand’s message, which is that the train disaster happened because people were put in charge who didn’t want to do their jobs and who only wanted a paycheck without making decisions or taking responsibility. In the novel, failure is always a failure of willpower; true capitalists can succeed at anything they put their mind to. The movie paints this catastrophe as a terrible accident, whereas in the book it’s an inevitable consequence of the evil that corrodes men’s souls under socialism.

This is an enormous thematic change, and I wonder whether the filmmakers did this deliberately or whether they even realized they were doing it. It’s tempting to speculate that it was intentional, that the stark and brutal message of Rand’s original – if you don’t agree with all her political opinions, you deserve to die and it will be your fault – was too much even for them to swallow. Alternatively, they might have worried that putting something so bloodcurdling on the screen would wipe out any possible sympathy the audience might have for their message, whatever their personal opinion.

Then again, I think it’s just as likely that the filmmakers simply missed the point. They made something that imitates the form of the novel, but misses the underlying philosophy. Say what you will about Rand’s morality or politics, but one thing she didn’t lack for was ambition. Her grandiose vision encompassed all of human history, which she imagined as a struggle between light and darkness that spanned the ages, culminating in a final, apocalyptic showdown in which the mentality of evil would devour itself and collapse once and for all. The filmmakers seem to have overlooked all of this, aside from the superficial moral of “rich capitalists are good, taxes and regulation are bad”.

Next week: We plunge into the third and final part of Atlas Shrugged. Stay tuned!

Other posts in this series: