Atlas Shrugged, part III, chapter I

After her conveniently minor plane-crash injuries have been treated, John Galt takes Dagny to the kitchen nook to make breakfast:

“Am I a guest here or a prisoner?” she asked.

“The choice will be yours, Miss Taggart.”

“I can make no choice when I’m dealing with a stranger.”

“But you’re not. Didn’t you name a railroad line after me?”

“Oh!… Yes… I did…” Then, remembering the rest, she added, “But I named it after an enemy.”

He smiled. “That’s the contradiction you had to resolve sooner or later, Miss Taggart.”

It’s a cute line about the two of them not being strangers, but of course it’s not true. Dagny has known John Galt for all of an hour at this point, maybe less. When she named the John Galt Line that, she thought the name was just part of a proverb; she didn’t know that it belonged to a real person.

No, the true reason for their instant rapport is that, in Rand’s world, all true capitalists share the same desires, the same outlook on life, the same aesthetic tastes, even the same personality. They’re as identical as worker bees. The next part of this chapter, where John Galt takes Dagny on a tour of the valley, consists of affirmation sessions where the inhabitants tell her their philosophy and she responds that she agrees with them about everything. It’s supremely ironic that Objectivism, which claims to exalt the individual above all else, doesn’t allow for any actual individuality. (This central paradox has often been pointed out, as in this letter by Murray Rothbard.)

She watched him as he stood at the stove, toasting bread, frying eggs and bacon. There was an easy, relaxed skill about the way he worked, but it was a skill that belonged to another profession; his hands moved with the rapid precision of an engineer pulling the levers of a control board.

…When he put her plate before her, she asked, “Where did you get that food? Do they have a grocery store here?”

“The best one in the world. It’s run by Lawrence Hammond.”

“What?”

“Lawrence Hammond, of Hammond Cars. The bacon is from the farm of Dwight Sanders — of Sanders Aircraft. The eggs and the butter from Judge Narragansett — of the Superior Court of the State of Illinois.”

This is something we’ll see more of later: in Galt’s Gulch, the millionaire capitalists are small farmers, growing crops or raising livestock to feed themselves. This, at least, makes sense, although Rand seems to underestimate how much time and labor subsistence farming requires, as she depicts the Gulchers as having ample free time left over for other pursuits, even second jobs.

“What is your job?” she asked. “Midas Mulligan said that you work here.”

“I’m the handy man, I guess.”

“The what?”

“I’m on call whenever anything goes wrong with any of the installations — with the power system, for instance.”

She looked at him — and suddenly she tore forward, staring at the electric stove, but fell back on her chair, stopped by pain.

… “The power system…” she said, choking, “the power system here… it’s run by means of your motor?”

“Yes.”

“It’s built? It’s working? It’s functioning?”

“It has cooked your breakfast.”

I said I’d give Ayn Rand credit for good lines, and this is one of them. Probably it’s because in this passage, unlike in most other parts of the book, Dagny acts like a human being with normal desires and emotional reactions. The doorstopper length of Atlas Shrugged, if it’s good for nothing else, allows for lots of dramatic build-up; and the quiet, low-key circumstances of this discovery strike a suitable contrast with Hank and Dagny’s long and hopeless quest to find the inventor of the motor.

“The young inventor of the Twentieth Century Motor Company is the one real version of the legend, isn’t it?”

“The one that’s concretely real — yes.”

… “You told them that you would stop the motor of the world.”

“I have.”

“What have you done?”

“I’ve done nothing, Miss Taggart. And that’s the whole of my secret.”

Although he doesn’t make an appearance until two-thirds of the way through, John Galt is unambiguously the hero of this story. But he’s a very strange kind of hero, almost like a negative image.

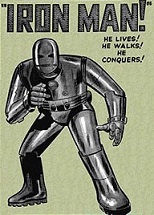

In the traditional picture, a hero fights for the cause of right, seeking no personal reward, selflessly sacrificing comfort, safety, even life if necessary to protect the innocent from evil. Think of comic-book superheroes like Batman or Iron Man, who dedicate themselves to the cause of justice, risking life and limb on a daily basis to stop supervillainous crime.

By contrast, John Galt’s heroic deeds consist of… doing nothing. Like Bruce Wayne or Tony Stark, he has a rigid moral code, a superhuman talent for invention and a copious supply of steely determination – the traditional traits of a hero. But rather than donning a cape and cowl or building a suit of powered armor, his whole plan is to hide out in a cabin in the mountains and wait for society to collapse. He has nefarious archenemies, but he doesn’t plan on doing anything to thwart their evil schemes. He doesn’t intend to help anyone besides himself, not now or at any time in the future, even though he knows that his inaction will cause millions of people to starve.

This isn’t just a quirk of the narrative. Ayn Rand’s philosophy requires this inverted view of heroism. As I noted in my original post on Objectivism back in 2008, Rand said flat-out that it was “immoral” to put oneself in jeopardy to save the life of a stranger, because in her worldview, you always have to put yourself and your interests first. You can take action to defend your own life and property, but that’s it.

This raises the question of who, in her utopia, would be the police, the firefighters, the military, the coast guard, the doctors and nurses on the front lines of epidemics – the first responders whose jobs demand that they face unknown and uncontrollable hazards. If everyone was an Objectivist, there would be no one to do these jobs, and society would come apart at the seams at the first crisis. Conveniently, in Galt’s Gulch, the issue never comes up because there’s no disease there, no fires, no natural disasters, no external threats, and no crime.

At least one of Rand’s enthusiasts tried to square this circle. Steve Ditko, the golden-age comic book artist, created the one and only Objectivist superhero: Mr. A, a crusading reporter who fights crime in a metal mask while delivering lectures on capitalism. Fittingly, given the all-or-nothing moral philosophy he inherits, he has no problem with consigning evildoers to death. Sadly, the comic ceased publication without offering any explanation for why a person who followed Rand’s philosophy of rational selfishness would risk his life to help others.

There’s only one way out of this problem, and it’s a way that Rand has alluded to before: with Ragnar Danneskjold, who risks his own life to wage a campaign of piracy against the looters and their relief ships (and who refers to himself as the Objectivist equivalent of a policeman). In his eyes, this is justified because he’s working for a cause he believes in – his efforts will help the world rebuild faster. But as I said at the time, Rand didn’t seem to realize that this tears a huge hole in her self-interest scheme. After all, if I define my selfish desire to be “wanting to help society become more peaceful and prosperous”, then I can rationally defend any action that serves humanity as a whole, even ones that Rand would have condemned with the dreaded word “non-profit”. That’s the dilemma that Objectivism has no solution for: either it can’t justify why people should do the jobs that society needs to survive – or it can justify anything that people decide of their own free will to do.

Other posts in this series: