Atlas Shrugged, part III, chapter I

Just as Dagny and John Galt prepare to set out, they have a visitor:

They were finishing breakfast when she saw Mulligan’s car stopping in front of the house. The driver leaped out, raced up the path and rushed into the room, not pausing to ring or knock. It took her a moment to realize that the eager, breathless, disheveled young man was Quentin Daniels.

“Miss Taggart,” he gasped, “I’m sorry!” The desperate guilt in his voice clashed with the joyous excitement in his face. “I’ve never broken my word before! There’s no excuse for it, I can’t ask you to forgive me, and I know that you won’t believe it, but the truth is that I — I forgot!”

Daniels is guilt-stricken at the thought that he almost got Dagny killed, so he’s relieved to see her all right. He confesses that he broke his promise to wait for her, explaining that John Galt came into his lab while he was locked in intense cogitation and wrote a single equation on the blackboard that was the key to everything he’d been searching for. The offer to leave with him on the spot was impossible to resist.

“And that’s the last I remember, Miss Taggart — I mean, the last I remember of my own existence, because after that we talked about static electricity and the conversion of energy and the motor.”

“We talked physics all the way down here,” said Galt.

… “I don’t blame you,” she said; she looked at him with a tinge of wistfulness that was almost envy. “Besides, you’ve fulfilled your contract. You’ve led me to the secret of the motor.”

“I’m going to be a janitor here, too,” said Daniels, grinning happily. “Mr. Mulligan said he’d give me the job of janitor — at the power plant. And when I learn, I’ll rise to electrician. Isn’t he great — Midas Mulligan? That’s what I want to be when I reach his age. I want to make money. I want to make millions. I want to make as much as he did!”

“Daniels!” She laughed, remembering the quiet self-control, the strict precision, the stern logic of the young scientist she had known. “What’s the matter with you? Where are you? Do you know what you’re saying?”

“I’m here, Miss Taggart — and there’s no limit to what’s possible here! I’m going to be the greatest electrician in the world and the richest! I’m going to—”

“You’re going to go back to Mulligan’s house,” said Galt, “and sleep for twenty-four hours — or I won’t let you near the power plant.”

“Yes, sir,” said Daniels meekly.

In the hands of any other writer, Daniels’ faith in unlimited advancement would be portrayed as touchingly naive. But it doesn’t seem that the text intends us to take his attitude for youthful exuberance. Rand clearly wants us to share the belief that Galt’s Gulch is a place where you can rise as high as your ambition takes you, and the one thing that all her protagonists have is unlimited supplies of ambition.

Even so, the laws of supply and demand can’t be denied, in this book of all places. Even if electricians stand to make as much as bankers in this society, which seems unlikely, the fact is that Galt’s Gulch has an electrician already, and his name is John Galt. Galt is relatively young and obviously has no intention of retiring any time soon. He’s already built a power plant which requires no fuel and which supplies the needs of every house in the valley. And considering that he’s able to spend most of his time roaming the world and recruiting other capitalists to join them, it must not need very much maintenance on a day-to-day basis.

So what, exactly, is Quentin Daniels going to do here? Who’s going to promote him, and to what position? What service does he offer that’s so valuable that the other inhabitants will pay him millions of dollars for it? We’ve established that John Galt is smarter than him; he’s casually created inventions that Daniels scarcely dreamed of. Whether or not Daniels has realized it yet, the particular talents he can claim are all redundant in this society. That janitorial job may be a lot more permanent than he thinks.

This is an implication of her utopia that Rand never addresses. Whatever she asserts about the dignity of work, what she’s shown us is a society made up entirely of the most ruthlessly competitive Type A personalities in the world. Which of them is going to volunteer for the humble, unglamorous, labor-intensive jobs, like hauling away the trash or mopping the floors – all the essential blue-collar jobs that nevertheless offer low pay and little hope of advancement – while their friends compose symphonies, lecture on philosophy, or get rich rebuilding the world’s industries? Galt’s Gulch has its executives, its artists and its doctors, but who’s going to be the garment workers, the short-order cooks, the cashiers, the groundskeepers, the fruit and vegetable pickers, the roofers, the construction workers, the night watchmen, the chimney sweeps?

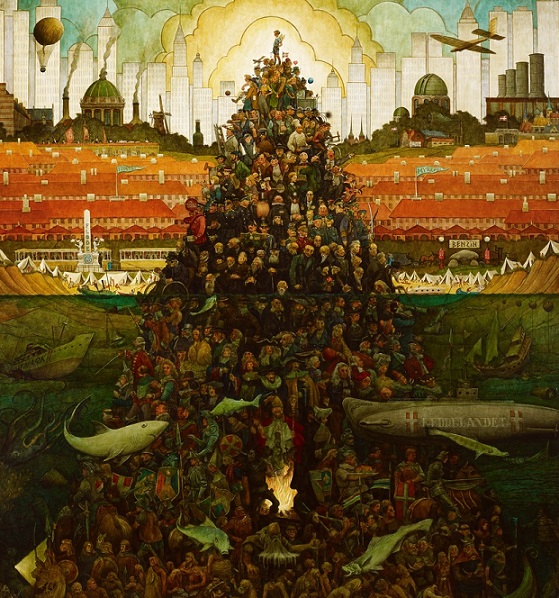

Rand’s vision of super-capitalists who can do anything glosses over the fact that almost any large company, however unrealistically competent its executives, depends on huge inputs of labor. (Even if one person can do anything, one person can’t do everything.) To have an economic pyramid, you have to have a lot of people on the bottom. And the pools of low-skilled, exploitable workers that they’d normally rely on just aren’t available in this small fishbowl of a society. Yet everyone Dagny meets in the Gulch intends to rise to the top of their respective industries and become rich and successful. Nowhere in the text, neither in dialogue nor in narration, is the impossibility of this pointed out. As with Garrison Keillor’s fictional Lake Wobegon, Rand seems to think you can have an economy where everyone is above-average.

We only ever get a brief glimpse of life in the Gulch, but if it developed along the usual lines, what’d most likely happen is that the first few capitalists would take the desirable jobs and quickly grow wealthy, while those who were recruited later on, like Daniels, would arrive expecting to get rich but would soon find that there were no jobs except low-paid, low-skilled manual labor. You can imagine for yourself how soon the social unrest would start, and how long it would be before this perfect capitalist utopia began to convulse and schism.

Image credit: Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Other posts in this series: