Atlas Shrugged, part III, chapter I

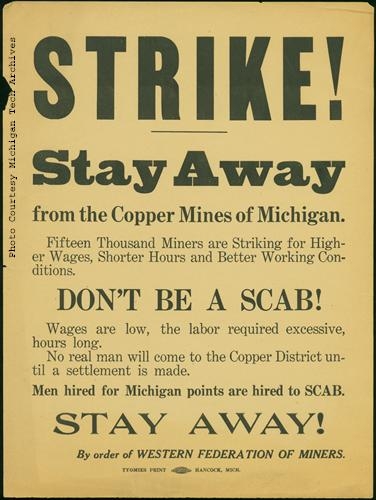

As we’ve seen previously, the supercapitalists hiding out in Galt’s Gulch call Dagny a “scab”, a grave insult for a worker who crosses a union picket line. Given that the word was coined by labor organizers, one might think Rand’s heroes were using it ironically – but it turns out they mean it in a very literal sense, as Dagny finds out when she asks them why they’ve quit their jobs and forsaken the world:

“Why?” she cried. “Why? What are you doing, all of you?”

“We are on strike,” said John Galt.

This is the cue for a Monologue expounding Rand’s view of civilizational development. According to John Galt, human survival in every age has only been made possible by rare, isolated geniuses – the “men of the mind” – who’ve come up with every invention from agriculture to mathematics, and who were invariably persecuted, imprisoned or killed by resentful inferiors by way of gratitude. Galt says that the men of the mind have always borne this treatment stoically, but that’s about to change:

“We’ve heard so much about strikes,” he said, “and about the dependence of the uncommon man upon the common. We’ve heard it shouted that the industrialist is a parasite, that his workers support him, create his wealth, make his luxury possible — and what would happen to him if they walked out? Very well. I propose to show to the world who depends on whom, who supports whom, who is the source of wealth, who makes whose livelihood possible and what happens to whom when who walks out.”

Hence, he says, the strike. When John Galt quit the Twentieth Century Motor Company, he made it his mission to search for the men of ability – “those bright flares in the growing night of savagery” – and to convince them that they should withdraw their talents from an ungrateful world. Midas Mulligan, who bought the valley piece by piece as a private resort, decided to throw the gates open after Galt persuaded him to join the strike. At first it was just a vacation retreat, but as the collapse of civilization accelerated, they decided to turn it into a permanent, self-sufficient home.

There’s an annihilating irony here that Ayn Rand was totally oblivious to. Her philosophy is the supreme exaltation of selfishness and individualism – the fierce rejection of the idea that human beings have any moral responsibilities or commitments toward each other. But in spite of all that, she’s scripted a plot where, in order to succeed, her heroes have to engage in collective action. To defeat the evil looters, they have to agree to work together and to subordinate their individual selfish desires to the greater good of the group.

After all, every capitalist in Galt’s Gulch is utterly dependent on the goodwill of the others. A single traitor could bring their whole scheme crashing down. What would happen if one of them – if Dagny, say – walked out of the valley and sent a message to the looter cabal in Washington: “The vanished industrialists are hiding out in a remote mountain valley in Colorado that Midas Mulligan bought before he disappeared”? Imagine the kingly rewards that person would stand to receive! Why are none of the I’ve-got-mine-so-screw-you, I-don’t-owe-you-anything supercapitalists even mildly tempted by the prospect?

The only way this plan can succeed is if no one in Galt’s Gulch ever wants to break faith or betray the others for any reason. It depends on no one ever being unhappy, disgruntled, or disillusioned to the extent that he would want to bring the whole society down. It depends on no one ever being outcompeted, driven into bankruptcy and poverty, and deciding to deliver the capitalists to their enemies on the grounds that it was better than starving. Even if someone merely wanted to leave to found a competing capitalist utopia in the next valley over, that would put them all at much greater risk of discovery.

In the bizarro world of Atlas Shrugged, none of these concerns ever arise. Rand’s ferocious individualists all agree completely with each other and trust each other to a degree that any communist state would envy. (Later on, they allow Dagny to leave the valley with only her word that she won’t reveal its existence.) This effortless solidarity clashes with the unsurprising fact that, when you put a lot of stubborn, cussed individualists and libertarians under the same roof, they tend not to get along.

A case in point is Joseph Silvestri, the chairman of the Nevada state Libertarian Party, who quit in frustration in 2013 because, he said, the party was “infested with idiots” who were only out for themselves and couldn’t work together on a political agenda. There’s also the Bundy Ranch secessionists, possibly the closest thing in the real world to Galt’s strike, who it turns out don’t have a lot in common other than disliking the government. Last year, two factions reportedly drew guns on each other after a heated dispute.

But Ayn Rand herself was the unsurpassable example. Late in life, she exiled countless people from her inner circle for even trivial slights or disagreements, complete with official blacklists and “kangaroo courts” (Anne C. Heller, Ayn Rand and the World She Made, p.267) where heretics were publicly condemned for their deviations from Objectivist orthodoxy. One of the anathematized was her former handpicked successor, Nathaniel Branden, who made the unforgivable mistake of falling in love with someone other than Rand (more on this later). Another ex-follower, Kay Smith, said, “One mistake was all it took to be drummed out for life” (p.398). By the time Rand died, she had driven away virtually every admirer she’d ever had.

There’s another passage that makes the unnatural harmony of Rand’s protagonists even clearer. It turns out that they could save the world – but all of them, to a man, are choosing not to:

“Given up?” said Hugh Akston. “Check your premises, Miss Taggart. None of us has given up. It is the world that has… All work is an act of philosophy. And when men will learn to consider productive work — and that which is its source — as the standard of their moral values, they will reach that state of perfection which is the birthright they lost… The source of work? Man’s mind, Miss Taggart, man’s reasoning mind. I am writing a book on this subject, defining a moral philosophy that I learned from my own pupil… Yes, it could save the world… No, it will not be published outside.”

If Akston isn’t just boasting – and remember, we’ve never seen a Randian hero make an idle boast – then the book he’s working on could save civilization, could make everyone reject the looters’ code and turn back to capitalism. But he refuses to publish, because he blames people for not already knowing what he had to say. (If everyone already knew it, what would be the point of writing the book?)

Instead, he and all the other capitalists plan to stay, safe and comfortable, in their mountain refuge and watch as civilization collapses and millions of people die. It’s hard to believe that none of the Gulchers have any problem with this, not on the obvious moral grounds, not even on the practical grounds that it’s easier to save the world than rebuild it from scratch. But no: this unbreakable collective commitment, this humanly impossible unanimity reigns among them. Did Ayn Rand really not notice?

Image credit: Keweenaw Digital Archives

Other posts in this series: