Atlas Shrugged, part III, chapter II

On the morning of her second day in the valley, Dagny wakes up in John Galt’s house (not in his bed – not yet, anyway). He greets her at the door, saying that he has to go out and fix some things:

“I have to go down to the powerhouse,” he said. “They’ve just phoned me that they’re having trouble with the ray screen. Your plane seems to have knocked it off key. I’ll be back in half an hour and then I’ll cook our breakfast.”

…She answered as casually, “If you’ll bring me the cane I left in the car, I’ll have breakfast ready for you by the time you come back.”

He glanced at her with a slight astonishment; his eyes moved from her bandaged ankle to the short sleeves of the blouse that left her arms bare to display the heavy bandage on her elbow. But the transparent blouse, the open collar, the hair falling down to the shoulders that seemed innocently naked under a thin film of cloth, made her look like a schoolgirl, not an invalid, and her posture made the bandages look irrelevant.

He smiled, not quite at her, but as if in amusement at some sudden memory of his own. “If you wish,” he said.

Once again, we see how fortunate Dagny is to have plot armor. That whole plane-crash thing only resulted in her being bandaged just enough to be even sexier, as opposed to, say, having major burns or being bedridden with two crushed legs.

In fact, no one ever gets hurt in this valley, even though the capitalists work long hours in all kinds of dangerous industries – lumberjacking, mining, working with heavy agricultural machinery, high voltages or molten metal. They seem to get by just fine with one doctor and no hospital. Could it be that John Galt and the others have unknowingly found Shangri-La, the mystical land with a life-giving aura of eternal youth and health, and are mistakenly attributing their thriving to their own efforts?

It was strange to be left alone in his house. Part of it was an emotion she had never experienced before: an awed respect that made her hesitantly conscious of her hands, as if to touch any object around her would be too great an intimacy. The other part was a reckless sense of ease, a sense of being at home in this place, as if she owned its owner.

It was strange to feel so pure a joy in the simple task of preparing a breakfast. The work seemed an end in itself, as if the motions of filling a coffee pot, squeezing oranges, slicing bread were performed for their own sake, for the sort of pleasure one expects, but seldom finds, in the motions of dancing.

In “Fiat Motors“, I wrote about the sheer implausibility of a single super-capitalist, no matter how talented, forging a piece of complex machinery from scratch by himself. But this passage has an even bigger implausibility, one that’s all the more glaring because Ayn Rand didn’t even notice it. I almost missed it the first time I read this chapter.

Where did Dagny get the ingredients for breakfast? Well, we’ve seen that they grow wheat, and it’s not too hard to believe they have a mill and a bakery to turn it into bread. (No doubt John Galt has already recruited the Best Baker in the World.)

Coffee is a little harder to believe, but OK. Midas Mulligan did say he has an agent who obtains things from the outside world, and it’s plausible that they stockpiled the beans.

But oranges? Fresh oranges? And the Gulchers have them in such abundance that they can afford to squeeze them?

Where did these come from, the famous citrus groves of Colorado? The Gulchers can’t still be having them shipped in, not at this point: the world is falling apart, all railroads and other transportation have become badly unreliable, and anyway, even a dull-witted looter would be bound to wonder why a carload of oranges is going to the middle of nowhere in the Rocky Mountains.

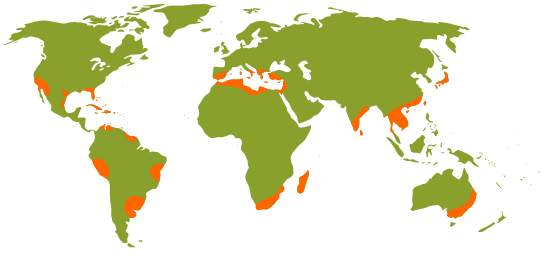

As I said earlier, it makes sense that nearly all the Gulchers are smallhold farmers, but they should be living at a subsistence level. Fresh fruit should be an expensive luxury at best, at worst unavailable for months at a time. This is especially true when it comes to tropical species like citrus trees, which are broad-leaved evergreens that are adapted to warm, sunny climates. Cold snaps can kill them, which is a perennial problem even in Florida. In Colorado, famous for its fierce winters and heavy snowfalls, growing them ought to be an absurd impossibility.

And it’s not just oranges whose presence here is inexplicable. There’s a part later in this chapter where Dagny goes into town and buys – for sixty cents – a “wide, cotton-print skirt”. Again, even assuming the Gulchers have mechanical harvesters, spinners and looms to aid with the immense labor of cotton picking and textile production, cotton requires a warm climate and can’t tolerate frost. Like oranges, woven cloth ought to be a rare and valuable commodity in the valley, not something you can just pick up at the market for a few pennies.

If these products are cheap and readily available in our world, that’s only because of the immense, submerged machinery of the global economy that cultivates, manufactures and transports them. None of that exists within the tiny fishbowl society of Galt’s Gulch, yet Rand doesn’t grasp that this presents any problem at all. In her thinking, environmental limitations don’t exist and supply chains are irrelevant. When you gather enough capitalists in one place, all the modern conveniences they want for themselves just appear, as if precipitating out of the air. It’s cargo cult economics, like the archetypal isolated tribesman who believes that carving a landing strip out of the jungle will summon airplanes.

Granted, Galt’s Gulch has an out that’s not available in reality, which is their free-energy motor. With unlimited energy, you could grow orange trees in industrial-sized greenhouses and keep them warm and illuminated year-round. To deal with the further problem that they’re high up in the mountains, where soil tends to be thin and acidic, they could also use their infinite energy to run the Haber-Bosch process night and day to produce fertilizer (although it would make a lot more sense for them to grow blueberries, which are from the heath family and well adapted to mountain climates and soils).

But this solution isn’t available outside of fiction, and there’s no hint that Rand even realized the necessity. There was an earlier scene where Dagny glimpses Richard Halley’s orchards, and we don’t hear about greenhouses or any other special arrangement or technology. And why would we? In Rand’s world, no pesky physical laws or natural limits apply to capitalism. The mere will to produce can bring about any desired outcome, from John Galt’s magic motor right down to the contents of his breakfast.

Header image credit: Liz West, released under CC BY 2.0 license

Other posts in this series: