Atlas Shrugged, part III, chapter II

While Ragnar Danneskjold thinks of himself as a reverse Robin Hood, I think he’s more like the Objectivist Santa Claus. He comes down the chimney to give gold to all the good girls and boys of superlative individual value. He may not have a sleigh drawn by flying reindeer, but he does have a stealth battleship which can both outrun and outfight all the navies of the world while simultaneously being small enough to hide undetectably, which we can safely say is equally magical. And instead of being fat and jolly, he’s icy blond and violent, although in Ayn Rand’s eyes that’s a bonus.

In John Galt’s breakfast nook, he explains his piratical plan to Dagny, adding that some of the gold he’s stolen is for her:

“…and the names of my customers, Miss Taggart, were chosen slowly, one by one. I had to be certain of the nature of their character and career. On my list of restitution, your name was one of the first.”

She forced herself to keep her face expressionlessly tight, and she answered only, “I see.”

“Your account is one of the last left unpaid. It is here, at the Mulligan Bank, to be claimed by you on the day when you join us.”

After Ragnar leaves, Dagny says angrily that she won’t accept the money, because she doesn’t want him endangering himself for her sake (because having known him for five minutes, she’s already adopted the other capitalists’ view that he’s just too pretty to put his life at risk). John Galt says she can’t stop him from doing that, and she replies that she can refuse to claim the gold, and that it will sit in her account at Midas Mulligan’s bank forever:

“No, it won’t. If you don’t claim it, some part of it — a very small part — will be turned over to me in your name.”

“In my name? Why?”

“To pay for your room and board.”

She stared at him, her look of anger switching to bewilderment, then dropped slowly back on her chair.

He smiled. “How long did you think you were going to stay here, Miss Taggart?” He saw her startled look of helplessness. “You haven’t thought of it? I have. You’re going to stay here for a month… I am not asking for your consent — you did not ask for ours when you came here. You broke our rules, so you’ll have to take the consequences. Nobody leaves the valley during this month. I could let you go, of course, but I won’t. There’s no rule demanding that I hold you, but by forcing your way here, you’ve given me the right to any choice I make — and I’m going to hold you simply because I want you here. If, at the end of a month, you decide that you wish to go back, you will be free to do so. Not until then.”

Wait, what? John Galt tells Dagny that because she trespassed on private property – even though she had no way of knowing it was private property, even though the owners did everything in their power to conceal that fact – she surrenders all her rights and can be dealt with or even disposed of however he sees fit (“any choice I make”).

Who gave him the authority to do that? If this is the law in the valley, who made that law? Who voted on it? Who found her guilty of breaking it, who was on the jury?

The text gives us the answer – John Galt says that he just made this law up on the spot and found her guilty of violating it. Apparently, he doesn’t need consent from anyone else: not Judge Narragansett, who’s the closest thing they have to a legal authority; not even Midas Mulligan, who’s supposed to be the owner of this place! Galt just decided that he’s going to hold Dagny prisoner for a month, and no one else in the valley has any say in the matter.

Critics have often said that Objectivist society would reduce to a feudal dictatorship, but this section makes the comparison a literal one. Under Objectivism, if someone trespasses on your property, even unintentionally, you can apparently enslave them and make them your indentured servant. Despite what Rand says about her ideal society having a minimal government and courts to adjudicate disputes according to objective law, her actual utopia relies on frontier-style self-help justice.

But it’s not just Ayn Rand who pays lip service to the rule of law but tramples all over the idea when it proves inconvenient. It’s a common affliction among libertarians who yearn, with varying degrees of openness, for a return to oligarchy.

One of the more explicit is Peter Thiel, the billionaire co-founder of PayPal, who wrote in 2009 that “I no longer believe that freedom and democracy are compatible,” and from context, it’s clear which one he’d prefer to jettison. But why has our once-great society gone down the tubes? According to him, the decline began when women got the right to vote:

Since 1920, the vast increase in welfare beneficiaries and the extension of the franchise to women — two constituencies that are notoriously tough for libertarians — have rendered the notion of “capitalist democracy” into an oxymoron.

Damn those women and their voting! Thiel doesn’t seem especially curious as to why women are “notoriously tough for libertarians”, but following up on last week’s post, let me suggest another hypothesis: many people find his pre-1920 definition of “freedom” somewhat lacking.

Thiel’s solution is for libertarians to cast off the shackles of society and escape, John Galt-like, into new frontiers that exist beyond the reach of oppressive law. The problem is that people have already tried experiments like this, and rather than becoming harmonious utopias of freedom, they tend to either collapse in scams and chaos or harden into de facto dictatorships.

One community that suffered a bit of both fates was Silk Road, an online black market for selling drugs, stolen credit cards and other illegal goods in anonymity. Silk Road’s creator, Ross Ulbricht, imagined it as a place where people would have “the freedom to make their own choices” free of law and regulation. The problem is that when transactions are conducted free of law and regulation, people can easily scam each other – and no surprise, that happened often (one ripped-off user famously complained, “I wish there were people who were honest crooks!”)

The culminating incident was when a Silk Road user threatened to leak the site’s customer list – in response to which, according to government allegations, Ulbricht tried to hire a hitman to murder the blackmailer. Alas for him, that was when the FBI swooped in to arrest him and shut the site down. As Henry Farrell reports in Aeon, Silk Road’s history ironically retraces the emergence of the state, with self-appointed rulers using violence as “the final argument of kings”.

It is no surprise to learn that other drug marketplaces on the secret internet are also responding to the same pressures by becoming ever more like miniature states; policing the industry of their members within, guarding ever more ferociously against dangers from without. Like Hobbes’s sovereign Leviathans, they are in continuous jealousies, maintaining internal industry while having their weapons pointed and eyes fixed upon each other.

There’s also the notorious story of the entrepreneurs who claimed to have created a real-life Galt’s Gulch in Chile, selling plots of land to the super-rich (gold and Bitcoins preferred!) so they could ride out an economic collapse in self-sufficient comfort. Chile is of course a functioning state, but at first that didn’t bother the buyers too much. However, the plan dissolved in lawsuits and acrimony when prospective customers found out there was a tiny problem with the land rights: to wit, the founders didn’t actually have them. One of the would-be residents, Canadian libertarian Wendy McElroy, wrote an angry blog post about her experience:

Months later, in a Skype conference, I asked the then-GGC-alienated salesman, “When you ‘sold’ us the property, when you printed out a photo from your phone that read ‘Wendy’s tree,’ did you know you could not legally sell us the lot you were offering?” He said, “That is correct.”

On Vice Media, Harry Cheadle sums up this affair:

Libertarians are normally wary of governments and other large organizations, but in this case they seem to have been too trusting of the idea of the Gulch in general and Johnson in particular. There’s nothing uniquely libertarian about putting faith in people who say they share your beliefs, or about wanting to build a utopia far from the grubby reality of your current home — but the idea that you can buy your way into paradise seems tailor-made for that political tribe. Looking back, it seems the problem was that the Gulchers weren’t as skeptical of the scheme as they should have been simply because it was spun by their ideological allies.

The lesson from these stories ought to be that there just aren’t any more desirable, unclaimed places where people can start society over, and the secessionists should learn to get along with the rest of us. Unfortunately for all concerned, that’s not a prospect they readily embrace. At best, they tend to make nuisances of themselves, as in the libertarian “Free Staters” in Keene, New Hampshire who made it their mission to harass police officers, only to find that the town residents didn’t ask to be “freed” and weren’t especially grateful for it.

At worst, they offer far more disturbing proposals. One example is Charles Murray, a libertarian political scientist and Jeb Bush’s favorite author, published a book called By the People in which he argues that democracy hasn’t “worked” (in that it hasn’t delivered his favored policy outcomes) and that the super-rich should just take control already.

Whether motivated by idealism or resentment, what all these people and groups have in common is their failure to grasp the purpose of the state. The state, just like money or capitalism, is an innovation that arose for a reason. It solves difficult problems of cooperation and coordination; it makes it possible for large numbers of people to live together peacefully. Ayn Rand got around this problem by writing all her characters to be incorruptibly honest and to have exactly the same beliefs and opinions. But real human beings rarely live up to that ideal, and when people imagine themselves to be Randian characters and try to live accordingly, they inevitably wind up coming to grief.

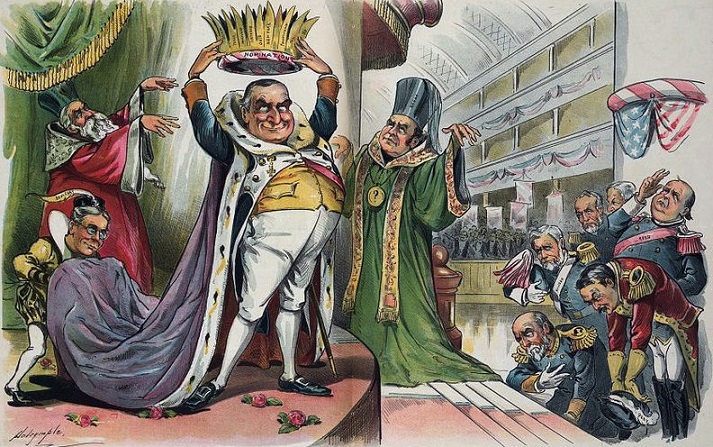

Image credit: Wikimedia Commons

Other posts in this series: