Atlas Shrugged, part III, chapter II

For all its fixation on economic theory, Atlas Shrugged shows a dismal, incurious ignorance of how the economy actually works. When Ayn Rand’s capitalists gather in sufficient numbers, consumer goods just spontaneously materialize around them. By all rights, the inhabitants of Galt’s Gulch ought to be living like primitive pioneers – wearing furs, dwelling in shacks, subsisting on a diet of salted meat and hardtack. Instead, they inexplicably have a fully industrialized society with all modern conveniences, from oranges to kitchen appliances to internal-combustion engines.

There’s no explanation of how a tiny pseudo-society, comprised of a thousand people or less, could have conjured up the complex manufacturing and supply chains necessary to create all these goods. This problem is made even worse by the fact that there seems to be no competition in the Gulch and only one person doing each job. This inevitably means that they’d suffer from a severe shortage of labor to power their manufacturing and agriculture, both of which are labor-intensive industries.

There’s one passage that shows Rand had at least a glimmering of the problem. Francisco d’Anconia is a superhumanly talented mining executive, but the idea of him operating an entire copper mine by himself was too implausible even for her. Which brings us to this:

D’Anconia Copper No. 1 was a small cut on the face of the mountain, that looked as if a knife had made a few angular slashes, leaving shelves of rock, red as a wound, on the reddish-brown flank.

The sun beat down upon it. Dagny stood at the edge of a path, holding on to Galt’s arm on one side and to Francisco’s on the other, the wind blowing against their faces and out over the valley, two thousand feet below.

This — she thought, looking at the mine — was the story of human wealth written across the mountains: a few pine trees hung over the cut, contorted by the storms that had raged through the wilderness for centuries, six men worked on the shelves, and an inordinate amount of complex machinery traced delicate lines against the sky; the machinery did most of the work.

…She looked at the spectacle of the most ingenious mining machinery she had ever seen, then at the trail where the plodding hoofs and swaying shapes of mules provided the most ancient form of transportation.

“Francisco,” she asked, pointing, “who designed the machines?”

“They’re just adaptations of standard equipment.”

“Who designed them?”

“I did. We don’t have many men to spare. We had to make up for it.”

We’re told that Francisco designed and built “machines” that do “most of the work” and make it possible for the Gulchers to run a copper mine with very little labor. Rand doesn’t seem to think this is especially noteworthy, since she doesn’t describe the nature or function of these machines in any further detail, and Francisco is dismissive about them.

But whether the narrative is aware of it or not, this is an invention as significant as John Galt’s perpetual-motion engine. It’s far more advanced than anything that exists today, let alone at the time this book was written. Real mining companies are switching to automation as fast as they can, like using driverless robot trucks to haul ore, but even they need more than six people to run a mine!

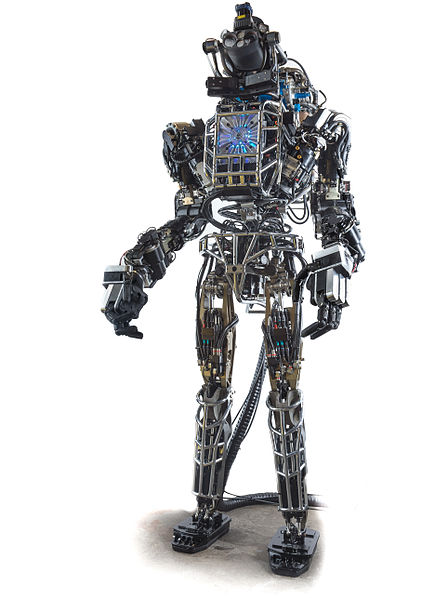

This, then, is Ayn Rand’s vision: the wealthy capitalists are served by robots that do their labor for them. This further drives home the point that Galt’s Gulch isn’t, and couldn’t be, a real society. It has a perfect climate, suitable for growing any crop, with no danger of bad weather or natural disasters. It has a limitless supply of energy, so its inhabitants never face any resource constraints. And it has robot laborers, so they can all live like lords and not have to do any of the tedious, backbreaking drudgery that a real economy requires. It’s a post-scarcity society like any other from science fiction.

As commenters have pointed out, this is intrinsic to Rand’s worldview. For all that she says about the dignity of toil and struggle, she also believes in a world where talent will be properly recognized and rewarded, as surely as day follows night. She’d never have written a novel where Dagny remained a lowly switch operator for life because her bosses refused to promote her, or where Hank Rearden worked as a laborer in the depths of a mine until he was old and broken. Her heroes have to end up on top, and since Galt’s Gulch is a society composed entirely of heroes, that raises the question of who’ll do the manual labor. Her solution was to invent near-magical technology to fulfill her protagonists’ every need, so that everyone can be an executive. But she didn’t realize how this undercuts her broader philosophy. If infinite energy and robot servants became commonplace, then we could have a society where work was largely unnecessary. The only people who’d still be employed would be the technicians who fix the robots.

This bears on the oft-heard libertarian argument that minimum-wage increases hurt the poorest workers by encouraging employers to replace them with automation. Obviously, if the technology exists for employers to replace workers (who need to be paid) with machines (which don’t), they can be counted on to do so regardless of what the wage scale is. And if automation ever advances to the point where not everyone needs to work to fulfill everyone’s needs – as it seems it has in the Gulch – then we’d practically have to come up with something to replace capitalism, or else accept that millions of people would be surplus to requirements and would starve to death.

Image: The appropriately named “Atlas” humanoid robot, built by Boston Dynamics and DARPA; via Wikimedia Commons

Other posts in this series: