Atlas Shrugged, part III, chapter II

Last time, John Galt told Dagny that while she was living in the capitalists’ valley, she could attend concerts or plays, just not his super-secret physics lectures. She takes him up on that suggestion:

[S]he sat among rows of benches under the open sky, watching Kay Ludlow on the stage. It was an experience she had not known since childhood — the experience of being held for three hours by a play that told a story she had not seen before, in lines she had not heard, uttering a theme that had not been picked from the hand-me-downs of the centuries. It was the forgotten delight of being held in rapt attention by the reins of the ingenious, the unexpected, the logical, the purposeful, the new — and of seeing it embodied in a performance of superlative artistry by a woman playing a character whose beauty of spirit matched her own physical perfection.

Now showing in Galt’s Gulch: “The Attractive People Win”, starring Kay Ludlow as Attractive Person! One night only! Doors open at 8:00 PM; no one will be admitted after 8:01 PM, because only moochers are ever late to anything.

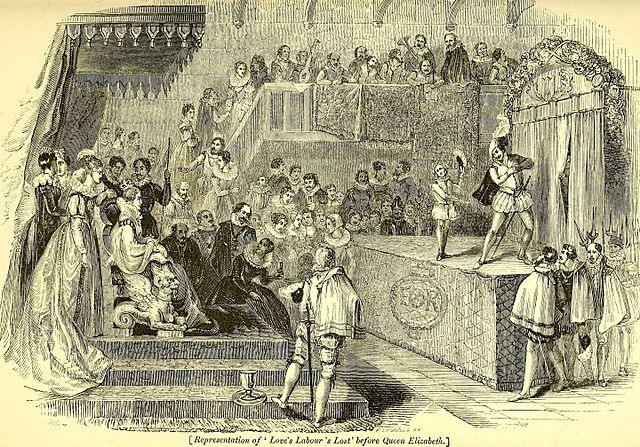

Rand’s jab at “the hand-me-downs of the centuries” suggests that in an Objectivist world, most of history’s great art and literature would be thrown in the trash for being insufficiently pro-capitalist. Only the ideologically correct plays and novels, the ones that precisely matched her own worldview, would continue to exist. The Ayn Rand Lexicon confirms that she condemned Shakespeare as the father of “naturalism” (her term for literature that “denies man’s volition”). While she liked that his characters embodied larger-than-life traits, she hated that many of them were doomed by inescapable destiny or tragic flaws. If only Hamlet had forgotten about that whole revenge thing and gone off to get rich by trading pickled-herring futures, that would really have been a play!

This goes to show how all-encompassing and cultish Rand’s philosophy was. It wasn’t just about belief in free-market capitalism and no-strings sex with whoever else believes in free-market capitalism. Rather, Objectivism was meant to dictate its followers’ tastes in every area of life, no matter how trivial. One former disciple recalled that in Rand’s inner circle, “There was more than just a right kind of politics and a right kind of moral code. There was also a right kind of music, a right kind of art, a right kind of interior design, a right kind of dancing” [from Jennifer Burns, Goddess of the Market, p.236].

This was most noticeable with music, one of Rand’s few sources of pleasure. Comically, her devotees scrambled to fall in line any time she expressed a preference: “The musicians in the group pretended to prefer Rachmaninoff – Rand’s favorite Romantic composer, a popular figure in the Russia of her youth – to the tragic, ‘malevolent’ Beethoven and the ‘pre-musical’ (meaning, pre-Romantic) Bach and Mozart. Once she described Brahms as ‘worthless,’ and Leonard Peikoff, a talented pianist who was perhaps Rand’s most reverential follower, rushed to give away his collection of Brahms recordings” [from Anne Heller, Ayn Rand and the World She Made, p.299].

“That’s why I’m here, Miss Taggart,” said Kay Ludlow, smiling in answer to her comment, after the performance. “Whatever quality of human greatness I have the talent to portray — that was the quality the outer world sought to degrade. They let me play nothing but symbols of depravity, nothing but harlots, dissipation-chasers and home-wreckers, always to be beaten at the end by the little girl next door, personifying the virtue of mediocrity. They used my talent — for the defamation of itself. That was why I quit.”

This is portrayed as comparable to all the other capitalists going on strike, but it’s really not. It’s possible to imagine, just, how a millionaire industrialist might get frustrated by government red tape preventing him from running his business as he sees fit. After all, you can’t just pack up and move a factory if you’re unhappy with the regulatory climate. But Kay Ludlow is an actress. If she’s unhappy about playing characters whose politics don’t match her own, why wouldn’t she just turn down those roles?

Also, Ayn Rand doesn’t tell us anything about the content of this play, which is too bad, because I have a question. Who were the other characters? Specifically, who plays the villain?

If Kay Ludlow objects to playing “symbols of depravity”, then all the other people in the valley ought to object as well, since they all share the same philosophy. None of them would be willing to play the bad guys; they’d all only audition for the role of heroes. Under those conditions, the only kind of play you could stage would be one that depicts something like the relationship between Dagny and Eddie, where he recognizes he’s not quite as great as her and subserviently defers to her desires. Alternatively, it could be a one-woman show where no one acts the part of the villains, although that properly ought to be called a monologue, not a play. (And as we know, Ayn Rand was a big fan of monologues.)

But the bigger problem is, wouldn’t all Objectivist plays and artworks be basically the same? The structure of the philosophy only allows for one kind of protagonist and one kind of story: heroic rich people who are unjustly downtrodden, then rise up and throw off the oppression of their inferiors. It’s the mirror image of Karl Marx’s idea of class struggle and historical progression, only with the winners and losers reversed. How many times can you tell that story before people start getting bored with it? How often do the Gulchers want or need to hear all the things they already believe affirmed to them yet again?

If the stories you tell are restricted to stale recitations of a single unvarying plot, that’s not art but propaganda. The role of art is to show us different facets of who and what we are. At its highest, it can reveal deep truths about human nature, even when it depicts circumstances far removed from those of the audience. That power of timeless insight is why Shakespeare and other authors are still renowned centuries after their deaths, even though they lived and wrote in a world very different from our own. But that’s just what Rand disclaims. She has no interest in showing people as they are, only as she thought they should be. This is why, for those who don’t share her lengthy list of assumptions, her characters will always seem weird, inhuman, or flat-out impossible.

Image credit: Wikimedia Commons

Other posts in this series: