Atlas Shrugged, part III, chapter III

Now that we’ve finished our tour of Galt’s Gulch, we’re back in the outside world with Dagny. From this point on, Atlas Shrugged is less of an economic-philosophical diatribe and more of a straightforward adventure story, so I anticipate that the rest of the book will go quicker. But there are a few more points to be made along the way.

This chapter opens with a scene about Robert Stadler, the once-great scientist who’s thrown in with the looters. As the scene opens, he’s grumpily wondering why he’s been summoned, perfunctorily and with no explanation, to a rural prairie in the middle of Iowa. A set of bleachers have been erected and are rapidly filling with people, journalists and politicians, all seemingly to observe an abandoned farm where some goats are browsing:

But it was the building that stood on a knoll some thousand feet away that gave Dr. Stadler a vague sense of uneasiness. It was a small, squat structure of unknown purpose, with massive stone walls, no windows except a few slits protected by stout iron bars, and a large dome… The building had an air of silent malevolence, like a puffed, venomous mushroom; it was obviously modern, but its sloppy, rounded, ineptly unspecific lines made it look like a primitive structure unearthed in the heart of the jungle, devoted to some secret rites of savagery.

Since it’s described as “sloppy” and “rounded”, you can probably guess that the purpose of this structure is for something evil. Stadler’s gnawing doubts are further reinforced by the nature of the crowd:

He turned to glance at the tiers behind him. The sensation he experienced was like a small, gray shock: that random, faded, shopworn assembly was not his conception of an intellectual elite. He saw defensively belligerent men and tastelessly dressed women — he saw mean, rancorous, suspicious faces that bore the one mark incompatible with a standard bearer of the intellect: the mark of uncertainty.

Uncertainty is incompatible with a standard-bearer of intellect. This might seem strange to you if you know any scientists, since what they mostly do is think up lots of different hypotheses and painstakingly test as many as they can, so they can judge which one is most likely to be correct. Uncertainty is part and parcel of that enterprise. But if you’re a Real Objectivist Scientist, you can skip all that tedious, time-wasting experimentation. You just sit and think, and when you stand up from your armchair, you’ll have a pure new scientific theory that’s 100% guaranteed to be correct.

Dr. Floyd Ferris, the looters’ henchman, is also on the scene. He rebuffs all Stadler’s questions, except to oleaginously assure him that the building, which he calls Project X or the Xylophone, is “a non-profit venture”. But once the crowd is fully assembled and the journalists are waiting eagerly, Ferris takes the podium and launches into a speech explaining that it’s a crucial scientific advance, derived from studies into the nature of sound. Then, as the crowd watches, comes the demonstration:

In the instant when he focused his lens, a goat was pulling at its chain, reaching placidly for a tall, dry thistle. In the next instant, the goat rose into the air, upturned, its legs stretched upward and jerking, then fell into a gray pile made of seven goats in convulsions. By the time Dr. Stadler believed it, the pile was motionless, except for one beast’s leg sticking out of the mass, stiff as a rod and shaking as in a strong wind. The farmhouse tore into strips of clapboard and went down, followed by a geyser of the bricks of its chimney. The tractor vanished into a pancake. The water tower cracked and its shreds hit the ground while its wheel was still describing a long curve through the air, as if of its own leisurely volition. The steel beams and girders of the solid new trestle collapsed like a structure of matchsticks under the breath of a sigh.

Project X is a weapon of mass destruction, with a range of a hundred miles – which encompasses “the bridge of the Taggart Transcontinental Railroad” that spans the Mississippi River. (Hmm, I wonder if that will be relevant later?) Ferris says that they could have given it a greater range, except that they couldn’t get enough Rearden Metal, as we saw in an earlier scene.

Dr. Stadler leaned back a little, his face austere and scornful, the face of the nation’s greatest scientist, and asked, “Who invented that ghastly thing?”

“You did.”

Dr. Stadler looked at him, not moving.

“It is merely a practical appliance,” said Dr. Ferris pleasantly, “based upon your theoretical discoveries. It was derived from your invaluable research into the nature of cosmic rays and of the spatial transmission of energy.”

“Who worked on the Project?”

“A few third-raters, as you would call them. Really, there was very little difficulty. None of them could have begun to conceive of the first step toward the concept of your energy-transmission formula, but given that — the rest was easy.”

Stadler is horror-stricken, realizing that the only possible purpose of a weapon like this is to suppress the population. But when the press gathers around him to ask for comment, he’s afraid to appear disloyal by denouncing the project. Instead, hating himself all the time, he reads a prepared speech that Ferris thrusts into his hands extolling the virtues of “his” great invention to bring peace and security.

This recalls the earlier discussion about what weapons manufacturers should do according to Rand’s philosophy. The text makes a big deal of Dr. Ferris’ insistence that Project X is “a non-profit venture”, which, combined with the building’s round shape, is a sure way to know that something is evil in Atlasworld. But would it have made a difference if it had been for profit? If Stadler had joined John Galt’s strike, instead of joining the looters, and had invented the same doomsday device, would it have been right and proper for him to sell it to the highest bidder, without regard for what they planned to do with it?

This chapter takes a stab at an answer:

Dr. Ferris smiled. “No private businessman or greedy industrialist would have financed Project X,” he said softly, in the tone of an idle, informal discussion. “He couldn’t have afforded it. It’s an enormous investment, with no prospect of material gain. What profit could he expect from it? There are no profits henceforth to be derived from that farm.”

Rand’s answer is that in a perfect capitalist world, no one would build weapons of mass destruction because there’s no profit in it, and therefore peace would reign. But this is just obviously wrong. In an Objectivist society, private citizens would buy weapons for the same reason they do now: to protect themselves and their property against threats, real or imagined. That’s bound to kick off an arms race, because how can you be sure of your safety if your neighbors have bigger guns than you do? And if you don’t trust those treacherous bastards next door, maybe it would be better to strike first, just in case…

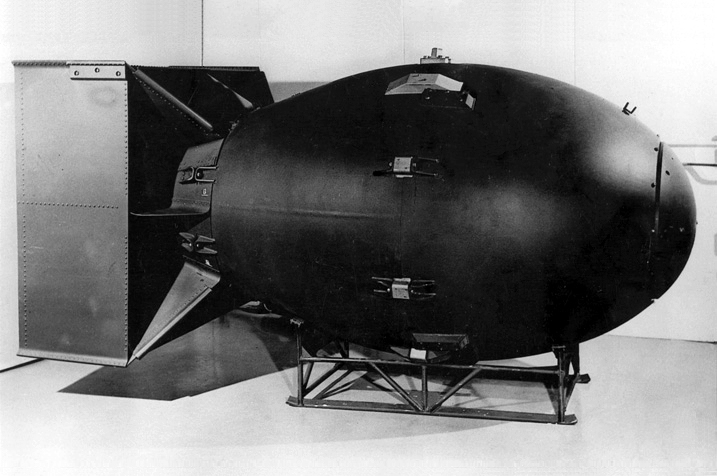

Project X is an obvious stand-in for the atomic bomb, which is a technology that never appears in Atlas Shrugged. Given Rand’s abhorrence for imaginary weapons of mass destruction, you might think that she’d have been against real-life WMDs too. But you’d be wrong:

In fact, she extols its creation as “an eloquent example of, argument for and tribute to free enterprise.” As evidence she cites the fact that despite its massive state power, Germany could not create the weapon but the United States did.

In her days as a Hollywood screenwriter, Rand wrote an outline for a never-produced film called Top Secret, which was to have been about the development of the atomic bomb. As with the space shuttle, she admired the A-bomb in spite of its being a government project start to finish. She insisted that it came about through the work of “free men in voluntary cooperation” and saw it as an achievement to be praised, since it could be used to hold off the world’s descent into “statism”. She went so far as to joke that God had planned the A-bomb as proof of the superiority of American capitalism [Anne C. Heller, Ayn Rand and the World She Made, p.189].

As befits her ex-nihilo attitude toward invention, Rand believed that all you really need is one great mind to come up with the crucial idea, and everything else follows trivially. The reality could hardly be more different.

Even when we knew that a nuclear chain reaction was possible, it wasn’t “easy” to build an atomic weapon. On the contrary, the atom bomb required effort on a colossal scale. The Manhattan Project’s uranium-enrichment facility in Oak Ridge, Tennessee was the biggest industrial operation in the world up to that point, and hundreds of local families were displaced to acquire the land to build it (the governor of Tennessee angrily declared this “an experiment in socialism“). Tens of thousands of workers were shipped in to run the plant, all of them working under tight top-down military control, in an atmosphere of such secrecy and security that few of them even knew what they were really doing or why until the first atom bomb was dropped. The project took the same “massive state power” that Rand decried in Germany, very far indeed from her rosy vision of “free enterprise” and “voluntary cooperation”. (Denise Kiernan’s The Girls of Atomic City is an excellent retelling of this story.)

Rand gives the A-bomb the credit for helping to stop the spread of “statism”. Mutually assured destruction may have prevented World War III, but arguably, what really held off communism wasn’t the atomic bomb, but the New Deal welfare state. Rand, who hated the New Deal, never even considered that Roosevelt’s policies may have “helped to save capitalism from its hungry dependents” and thereby “stave[d] off a Russian-style insurrection” [Heller, p.133] in the U.S. According to Bruce Bartlett, policy analyst in two Republican administrations: “there are sound reasons why a conservative would support a welfare state… masses of poor people create social instability and become breeding grounds for radical movements. In postwar Europe, conservative parties were the principal supporters of welfare-state policies in order to counter efforts by socialists and communists to abolish capitalism altogether.” In “A Conservative Case for the Welfare State“, he argues that the social safety net is “essential to the operation of a free market”.

In Rand’s dream world, the desperately poor will peacefully starve to death if they lose their jobs, so no social welfare programs are necessary, and the super-rich will peacefully resolve their disputes without turning to force, so no mass-destruction weapons will exist. Since she only cared about idealized people, human nature as it is didn’t interest her, and so inevitably, neither did the world as it really is.

Image: A replica of “Fat Man”, the nuclear bomb dropped on Nagasaki in August 1945. Despite its being heavy and rotund, Ayn Rand viewed this as the good, capitalist kind of weapon. Via Wikimedia Commons.

Other posts in this series: