Atlas Shrugged, part III, chapter V

It’s now been two months since Dagny returned from Galt’s Gulch. Taggart Transcontinental is suffering through an agonizing, protracted collapse, with breakdowns halting trains and snarling schedules all across the country. The few spare parts they can get are being stolen and sold on the black market by Cuffy Meigs, the looter official from Washington who’s now the sole one making decisions for the railroad.

Dagny is in Jim’s office, where he’s pleading with her to do something:

She sat looking at the ancestral map of Taggart Transcontinental on the wall of his office, at the red arteries winding across a yellowed continent. There had been a time when the railroad was called the blood system of the nation, and the stream of trains had been like a living circuit of blood, bringing growth and wealth to every patch of wilderness it touched. Now, it was still like a stream of blood, but like the one-way stream that runs from a wound, draining the last of a body’s sustenance and life.

Jim is convinced that Dagny could save the railroad from all its troubles if she really wanted to. To his shock, she tells him there’s nothing she can do (“I told you where your course would take you. It has”). Instead, she suggests, he should quit and get out of the way – “you and your Washington friends and your looting planners and the whole of your cannibal philosophy” – so that she and the remaining capitalists can salvage what’s left. He doesn’t take it well:

“Dagny”—his voice was the soft, nasal, monotonous whine of a beggar—”I want to be president of a railroad. I want it. Why can’t I have my wish as you always have yours? Why shouldn’t I be given the fulfillment of my desires as you always fulfill any desire of your own? Why should you be happy while I suffer? Oh yes, the world is yours, you’re the one who has the brains to run it. Then why do you permit suffering in your world? You proclaim the pursuit of happiness, but you doom me to frustration. Don’t I have the right to demand any form of happiness I choose? Isn’t that a debt which you owe me? Am I not your brother?”

As exaggerated and distorted as this is, I think it’s one of the few places where a true insight about human nature glimmers through. Any political philosophy has to come to terms with the fact that there are people who aspire to dependence, who expect others to provide for their wants and carry them through life. That said, I’m not endorsing conservative stereotypes about the lazy poor! If anything, it’s the rich and privileged who most often live by rent-seeking and expect others to cater to their whims. Being passive is a luxury that the poor rarely have.

I don’t think anyone should be left to starve in a rich society, but we do need an incentive for people to contribute, to use the talents and skills they have for everyone’s benefit. That’s why competition will always have a role to play in the economy. However, it’s possible to go too far.

Dagny is certain that if only the looters would get out of the way and let the capitalists run their businesses according to Objectivist principles, nothing could go wrong. She’s convinced that even on the brink of collapse, they’d be able to bring the country back just by doing what comes naturally. But real-world experience argues otherwise.

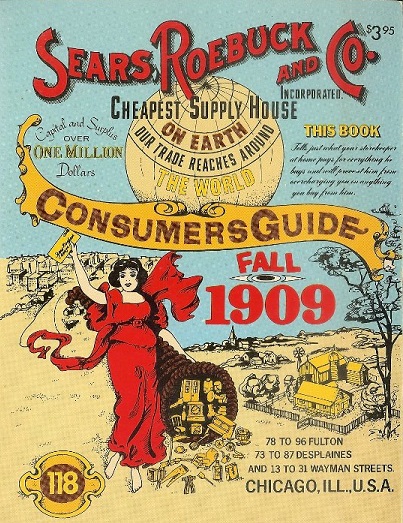

Take the story of Eddie Lampert. A billionaire hedge-fund investor and devotee of Ayn Rand, he took over the struggling retailer Sears in 2013. As his turnaround plan, Lampert had what he must have thought was a brilliant idea: why not have the departments of the company compete against each other, as if they were separate businesses?

If the company’s leaders were told to act selfishly, he argued, they would run their divisions in a rational manner, boosting overall performance.

Under the assumptions of Objectivism, where people are incorruptibly moral automatons, this system would have given everyone incentive to work as hard as they possibly could, and the company would prosper. Under a more realistic view of human nature, it should’ve been obvious what would and did happen: it gave everyone an incentive to sabotage their co-workers.

The Businessweek article describes a business “ravaged by infighting as its divisions battle over fewer resources”. Marketing meetings degenerated into screaming matches as executives fought for space in advertising circulars. “Turf wars sprang up over store displays. No one was willing to make sacrifices in pricing to boost store traffic… Former executives say they began to bring laptops with screen protectors to meetings so their colleagues couldn’t see what they were doing.” The infighting threw Sears into a downward spiral from which it’s yet to recover. Just this week, its stock was said to be “in unstoppable decline“.

Sears isn’t the only corporation that’s tried this. There’s Microsoft’s notorious system of “stack ranking“, in which employees were graded on a bell curve. Some had to be labeled as underperformers, no matter how good at their jobs they were. This almost universally despised system cratered employee morale and arguably contributed to Microsoft’s missing out on major innovations like the smartphone. Before it went bankrupt, the energy giant Enron had a similar system called “rank and yank“, which some observers have blamed for encouraging the sort of gamesmanship and short-term thinking that led to the company’s implosion.

There’s another passage I want to call attention to. In it, Rand repeats her insistence that there’s no difference between humanitarians who genuinely want to help others and villains who just want to loot and plunder. Both of them, she says, take the same actions and result in the same outcome: taking money away from the deserving and giving it to the undeserving.

There was no way to tell which devastation had been accomplished by the humanitarians and which by undisguised gangsters. There was no way to tell which acts of plunder had been prompted by the charity-lust of the Lawsons and which by the gluttony of Cuffy Meigs — no way to tell which communities had been immolated to feed another community one week closer to starvation and which to provide yachts for the pull-peddlers. Did it matter? Both were alike in fact as they were alike in spirit, both were in need and need was regarded as sole title to property, both were acting in strictest accordance with the same code of morality.

Something I’ve noted before is that there are no characters in Atlas Shrugged who are honestly mistaken. No one acts out of real (even if misplaced) compassion for the poor and the needy. Everyone who isn’t a ruthlessly selfish capitalist is a leering looter who just wants to drain the life of the productive people for the sake of evil. You and I might see that as jousting at straw men, but Rand doesn’t. In her view, there’s no difference.

There’s one other plot development in this chapter. While Dagny is in Jim’s office, he tells her he has some news for her. He knows of a plot to nationalize d’Anconia Copper that’s been in the working for some time, and he wants her to hear about it so that he can gloat. He turns on the radio, expecting to hear the news announcing the seizure, but instead there’s this emergency exposition from a Chilean broadcaster:

“On the stroke of ten, in the exact moment when the chairman’s gavel struck the rostrum, opening the session — almost as if the gavel’s blow had set it off — the sound of a tremendous explosion rocked the hall, shattering the glass of its windows. It came from the harbor, a few streets away — and when the legislators rushed to the windows, they saw a long column of flame where once there had risen the familiar silhouettes of the ore docks of d’Anconia Copper. The ore docks had been blown to bits.

They soon discover that there’s nothing left of d’Anconia Copper. Every office building has been blown up, every mine either buried under tons of collapsed rock or found to be exhausted, and every worker given their last paycheck in cash and ushered out the door. All the looters, including Jim Taggart, who were counting on a share of Francisco’s seized property have been ruined.

“Ladies and gentlemen, the d’Anconia fortune — the greatest fortune on earth, the legendary fortune of the centuries — has ceased to exist. In place of the golden dawn of a new age, the People’s States of Chile and Argentina are left with a pile of rubble and hordes of unemployed on their hands.

No clue has been found to the fate or the whereabouts of Señor Francisco d’Anconia. He has vanished, leaving nothing behind him, not even a message of farewell.”

The text treats this as Francisco’s finest hour, his ultimate revenge on a world that wouldn’t give him the worship he deserved. But as I said earlier, this is cheating. The whole point of the book is supposed to be that the world can’t survive without the productive genius of the capitalists. But this enormous and elaborately planned act of sabotage, designed to deny the bad guys any resource that might be of use to them, disproves that assertion.

You may remember Francisco’s explanation for why he ruined his own company – “it could have lasted and helped them to last” – which is an admission that he’s not as irreplaceable as he thinks. If his presence were really as necessary as all that, he wouldn’t have had to blow anything up, he could have just walked out. Later in the chapter, we’ll see that Francisco’s action directly causes a mass famine that results in the death of millions of people, but that never enters into the author’s moral evaluation of him as a person either now or later.

Other posts in this series: