Atlas Shrugged, part III, chapter VII, The Speech

There’s a character who’s missing from Atlas Shrugged.

His name is Father Amadeus, and while he was part of Ayn Rand’s early outlines, she jettisoned him from the final draft. He was to have been a Catholic priest affiliated with the Taggarts who heard James’ confessions. In the denouement, he would have realized that John Galt was right and that forgiveness is evil, and when the bad guys came to him one last time, he would have refused to grant them absolution.

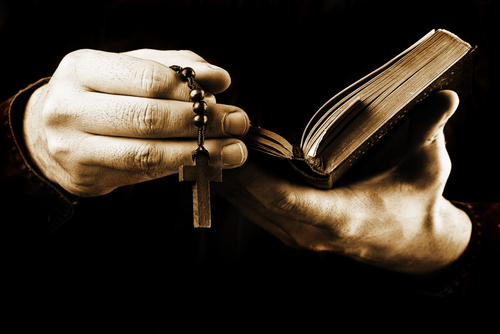

Rand discarded Father Amadeus because she couldn’t find a place to fit him into. To have him join the good guys would have implied that Christianity should persist in the capitalists’ utopia, which she didn’t believe. But his absence points to one more thing that’s missing from this novel: there’s no religion in Randworld, not really. Aside from the weird and brief scene with Ivy Starnes and Buddhism, no one in this book ever prays, goes to church, reads the Bible, or appeals to the will of God to justify their actions. A few characters use “God!” or “Christ!” as oaths, but aside from that, it’s as if religion and all its appurtenances simply don’t exist.

Since Rand was an avowed atheist, you’d think she’d have made her villains extra-religious. Having the bad guys flaunt their piety would have been one way to explain why people followed them in spite of their failures. And since religion has always preached the virtues of asceticism, self-sacrifice and pie in the sky, it’d have made an excellent foil for the capitalists.

But no. The bad guys are just as all-consumingly devoted to business and industry as the heroes, only in an evil way. Ironically, this disdain for religion was one of the few traits Rand had in common with the communists. In most respects, she took whatever they believed and did the opposite.

However, there is one part of the Monologue where John Galt rails against religion. Let’s watch:

“Damnation is the start of your morality, destruction is its purpose, means and end. Your code begins by damning man as evil, then demands that he practice a good which it defines as impossible for him to practice…

The name of this monstrous absurdity is Original Sin.

A sin without volition is a slap at morality and an insolent contradiction in terms: that which is outside the possibility of choice is outside the province of morality. If man is evil by birth, he has no will, no power to change it; if he has no will, he can be neither good nor evil; a robot is amoral. To hold, as man’s sin, a fact not open to his choice is a mockery of morality. To hold man’s nature as his sin is a mockery of nature. To punish him for a crime he committed before he was born is a mockery of justice. To hold him guilty in a matter where no innocence exists is a mockery of reason. To destroy morality, nature, justice and reason by means of a single concept is a feat of evil hardly to be matched.

…Do not hide behind the cowardly evasion that man is born with free will, but with a ‘tendency’ to evil. A free will saddled with a tendency is like a game with loaded dice. It forces man to struggle through the effort of playing, to bear responsibility and pay for the game, but the decision is weighted in favor of a tendency that he had no power to escape. If the tendency is of his choice, he cannot possess it at birth; if it is not of his choice, his will is not free.”

Rand’s atheism is one thing I agree with her about, so this part of the book I genuinely liked. Her dissection of original sin, and why it’s a moral absurdity to blame people for having a nature they didn’t choose, are sharp and to the point. I’ve made similar arguments myself. An omnipotent creator wouldn’t have given humans character traits he didn’t want them to act on.

However, this passage unintentionally spotlights something else, which is that as in so many other things, Rand was the mirror of what she despised. Her theology – because that’s what it is – is essentially the same as Christianity, except with John Galt in place of God as the supreme image of virtue and the ultimate judge of the world. Like Christianity, it divides all of humanity into two castes, the saved (the producers) and the damned (the moochers). And like most forms of Christianity, it attributes people’s fates solely to “free will”, without inquiring what that magical ability consists of.

You can see why Rand was so nervous about evolution (or education, for that matter). The wellsprings of human nature – why we are the kind of beings we are, why people make the choices they do – were a dangerous shoal that she steered a wide course around.

I agree that it’s irrational to blame people for something they had no choice over. But I conclude from this that some people behave badly through no fault of their own, and need help to become the better people they have the potential to be. Rand’s philosophy insists that everything is subject to choice, that human beings can bootstrap themselves into existence, and that everyone bears sole responsibility for what they become regardless of the privileges they enjoyed or the deprivations they suffered from. She has to assert that nothing in anyone’s background matters, lest she have no choice but to admit that some people are playing in a “game with loaded dice”.

There’s another passage from John Galt’s speech that stresses the irony:

“Your code divides mankind into two castes and commands them to live by opposite rules: those who may desire anything and those who may desire nothing, the chosen and the damned, the riders and the carriers, the eaters and the eaten.”

But as we’ve seen over the past three years, this critique applies to Rand in the exact same way! She, too, divides humanity into two castes of heroic producers and lowly looters; and she, too, insists that her chosen ones are entitled to anything they want (extramarital affairs, unlimited wealth, immunity from inconvenient laws, groveling deference from the masses), while the rest of humanity has no right to seek the fulfillment of their desires and indeed should thank the capitalists for merely permitting them to exist.

One more quote from John Galt:

“What is the nature of the guilt that your teachers call his Original Sin? What are the evils man acquired when he fell from a state they consider perfection? Their myth declares that he ate the fruit of the tree of knowledge — he acquired a mind and became a rational being.

It was the knowledge of good and evil — he became a moral being. He was sentenced to earn his bread by his labor — he became a productive being. He was sentenced to experience desire — he acquired the capacity of sexual enjoyment. The evils for which they damn him are reason, morality, creativeness, joy — all the cardinal values of his existence… Whatever he was — that robot in the Garden of Eden, who existed without mind, without values, without labor, without love — he was not man.”

This is a very clever argument, and again, I’d agree. In “Bright Machines“, I wrote about how Christian attempts to depict their ideal, sinless state of being invariably come off as flat, lifeless and mechanical. The ordinary emotions and desires they condemn as sin are the very things that give depth and color to our lives.

Needless to say, Rand’s outspoken atheism has always been a source of dismay to religious conservatives who love her laissez-faire economics and her let-them-eat-cake ruthlessness. It’s probably the reason why her writing never attained a greater prominence in Republican Party dogmas than it has. Paul Ryan, for example, publicly backed away from his devotion to Rand after he was criticized over it, although other conservative figures who’ve faced less scrutiny continue to praise her.

Rand herself would have been furious at the thought that anyone could accept her economics but not her atheism (or vice versa). As far as she was concerned, her philosophy was only on offer as a package deal. To agree with parts of it, but not all of it, made you worse than any looter in her eyes. (She was a fierce enemy of the then-new Libertarian Party for this reason.) In this way, too, she was far more like the religious dogmatists she rejected than she would ever have acknowledged.

Other posts in this series: