Atlas Shrugged, part III, chapter VIII

The looter government’s radio appeals to John Galt are getting desperate. They promise to meet whatever terms he sets, to follow any orders he gives if he’ll just help them, but there’s no hint of an answer. The bad guys keep badgering Dagny in the (entirely justified and accurate) hope that she knows something:

“Miss Taggart, we don’t know what to do,” said Mr. Thompson; he had summoned her to a personal conference on one of his scurrying trips to New York. “We’re ready to give in, to meet his terms, to let him take over — but where is he?”

“For the third time,” she said, her face and voice shut tight against any fissure of emotion, “I do not know where he is. What made you think I did?”

…She was at the door when he sighed and said, “I hope he’s still alive.”

That brings Dagny up short, and she turns back and asks Mr. Thompson what he means by that:

He shrugged, spreading his arms and letting them drop helplessly.

“I can’t hold my own boys in line any longer. I can’t tell what they might attempt to do. There’s one clique — the Ferris-Lawson-Meigs faction — that’s been after me for over a year to adopt stronger measures. A tougher policy, they mean. Frankly, what they mean is: to resort to terror. Introduce the death penalty for civilian crimes, for critics, dissenters and the like…. Nothing will make our system work, they say, but terror. And they may be right, from the look of things nowadays. But Wesley won’t go for strong-arm methods; Wesley is a peaceful man, a liberal, and so am I. We’re trying to keep the Ferris boys in check, but…”

The extreme reluctance of Atlas’ villains to actually commit villainy is one of the strangest parts of this very strange book. Ayn Rand came from a totalitarian state; she was perfectly familiar with terror as a tool of oppressive governments. Yet the antagonists in this novel have no gulags, no secret police, no labor camps, no firing squads. Even on the very brink of total collapse, with their backs against the wall, the worst evil they can conceive of is raising taxes. There’s one instance of torture later on, but by all historical precedent it should have become routine long before now.

This is even more striking in light of the fact that the heroes aren’t averse to getting their way through terrorism and violence. From small-scale cruelties like Francisco hitting and raping Dagny, Dagny’s threats to murder people or Hank Rearden cowing his wife into silence by threatening to beat her, to mass campaigns of piracy and sabotage against oil wells, mines, docks and cargo ships, the use of violence is practically a defining trait of Randian protagonists. And on top of everything else, they have the gall to insist that they’re the peaceful ones who oppose initiation of force!

If the novel didn’t tip its hand by emphasizing the heroes’ angular beauty and the looters’ rotund ugliness, you’d never guess which side you were supposed to root for. The same events, looked at from another perspective, could be a story about a gang of supervillains who pull off a plot to destroy the world. Perhaps that’s the answer of why the villains aren’t so villainous: in the author’s eyes, they didn’t need to be, because Rand was so confident in the invincible righteousness of her cause that it didn’t even occur to her that anyone might not judge these events the same way she did.

“You see, they’re set against any surrender to John Galt. They don’t want us to deal with him. They don’t want us to find him. I wouldn’t put anything past them. If they found him first, they’d — there’s no telling what they might do… That’s what worries me. Why doesn’t he answer? Why hasn’t he answered us at all? What if they’ve found him and killed him?”

Dagny feels a wash of fear at this thought, but holds herself together long enough to make her excuses and depart. But when she leaves, she heads straight for John Galt’s residence, using the address she got from Taggart employee records. It turns out to be a crumbling, Jacob Riis-esque tenement on the lower east side of Manhattan (ah, the good old days before gentrification):

She looked at the shapes of the slums, at the crumbling plaster, the peeling paint, the fading signboards of failing shops with unwanted goods in unwashed windows, the sagging steps unsafe to climb, the clotheslines of garments unfit to wear…

Some memory kept struggling to reach her, then came back: its name was Starnesville. She felt the sensation of a shudder. But this is New York City! — she cried to herself in defense of the greatness she had loved; then she faced with unmoving austerity the verdict pronounced by her mind: a city that had left him in these slums for twelve years was damned and doomed to the future of Starnesville.

Since Rand seems to have forgotten her own plot, let me point out that the world didn’t “leave him” anywhere. In fact, the looters are eagerly searching for him so they can put him in charge of the country! John Galt is living in this slum by his own choice, deliberately refusing to use his talents for the common good of humanity.

It’s unclear whether Dagny objects to slums per se, or just to the fact that John Galt is living in one of them. That it reminds her of Starnesville seems to imply that she takes its existence as an indictment of society, and that in a world run by real capitalists there wouldn’t be such places. (If so, permit me to introduce you to the last three hundred years of capitalism.) But we’ve also repeatedly seen the protagonists’ disdain for anything that helps the poor.

She finds his room at the back of the building. “John Galt” is even written on a nameplate by the door. Driven by her desperate desire to know whether he’s alive, she climbs the steps and rings the bell:

…[T]he figure standing on the threshold was John Galt, standing casually in his own doorway, dressed in slacks and shirt, the angle of his waistline slanting faintly against the light behind him.

… “John… you’re alive…” was all she could say.

He nodded, as if he knew what the words were intended to explain.

Then he picked up her hat that had fallen to the floor, he took off her coat and put it aside, he looked at her slender, trembling figure, a sparkle of approval in his eyes, his hand moving over the tight, high collared, dark blue sweater that gave to her body the fragility of a schoolgirl and the tension of a fighter.

“The next time I see you,” he said, “wear a white one. It will look wonderful, too… If there is a next time,” he added calmly.

Dagny asks what he means, and John Galt says that in all likelihood she was followed – that even the looters are smart enough to know she’s their last chance to find him. He knew this would happen, that she wouldn’t be able to keep away from him forever, and that he doesn’t blame her or regret it. However, they have only a few minutes before every policeman in the district converges on the building.

“I wasn’t followed! I watched, I—”

“You wouldn’t know how to notice it. Sneaking is one art they’re expert at. Whoever followed you is reporting to his bosses right now. Your presence in this district, at this hour, my name on the board downstairs, the fact that I work for your railroad — it’s enough even for them to connect.”

He says that there’s only one way for either of them to escape alive. Even if they capture him, the villains have no power over him, nothing to hold over his head to force him to do their bidding – except for one thing. If the looters find out about their relationship, they’ll torture Dagny to coerce him, and if that happens, he’ll commit suicide rather than live as their slave. The only hope is for Dagny to turn against him, to claim she tracked him down for the reward on his head.

“You must take their side, as fully, consistently and loudly as your capacity for deception will permit. You must act as one of them. You must act as my worst enemy. If you do, I’ll have a chance to come out of it alive.”

With trepidation, Dagny agrees to this plan. She asks if he’s heard the radio appeals they’ve been sending out to him every night, and he says, “Sure.”

She glanced slowly about the room, her eyes moving from the towers of the city in the window to the wooden rafters of his ceiling, to the cracked plaster of his walls, to the iron posts of his bed. “You’ve been here all that time,” she said. “You’ve lived here for twelve years… here… like this…”

“Like this,” he said, throwing open the door at the end of the room.

She gasped: the long, light-flooded, windowless space beyond the threshold, enclosed in a shell of softly lustrous metal, like a small ballroom aboard a submarine, was the most efficiently modern laboratory she had ever seen.

…He pointed to an unobtrusive object the size of a radio cabinet in a corner of the room: “There’s the motor you wanted,” and chuckled at her gasp, at the involuntary jolt that threw her forward…

She was staring at the shining metal cylinders and the glistening coils of wire that suggested the rusted shape resting, like a sacred relic, in a glass coffin in a vault of the Taggart Terminal.

This romantic sight drives the two of them to a passionate embrace, until they’re interrupted by the ringing of the doorbell:

Her first reaction was to draw back, his — to hold her closer and longer.

When he raised his head, he was smiling. He said only, “Now is the time not to be afraid.”

…Three of the four men who entered were muscular figures in military uniforms, each with two guns on his hips, with broad faces devoid of shape and eyes untouched by perception. The fourth, their leader, was a frail civilian with an expensive overcoat, a neat mustache, pale blue eyes and the manner of an intellectual of the public-relations species.

The leader asks him if he’s John Galt, which he admits (“That’s my name”), but he denies being the John Galt who spoke on the radio. Dagny plays her role:

“Don’t let him fool you.” The metallic voice was Dagny’s and it was addressed to the leader. “He — is — John — Galt. I shall report the proof to headquarters. You may proceed.”

With a false front of joviality, the leader of the gang says that it’s an honor and a privilege to meet John Galt in person. He assures him that they’re not his enemies and he’s not under arrest, it’s just that the leaders of the country urgently need to meet with him. But before they can take him to that meeting, there’s a technicality – they have to search his room:

“Locked!” declared a soldier, banging his fist against the laboratory door.

The leader assumed an ingratiating smile. “What is behind that door, Mr. Galt?”

“Private property.”

“Would you open it, please?”

“No.”

When Galt refuses to cooperate, the policeman orders one of his men to break the door down.

The wood gave way easily, and small chips fell down, their thuds magnified by the silence into the rattle of a distant gun. When the burglar’s jimmy attacked the copper plate, they heard a faint rustle behind the door, no louder than the sigh of a weary mind. In another minute, the lock fell out and the door shuddered forward the width of an inch.

…Dagny followed them, when they stepped over the threshold, preceded by the beams of their flashlights. The space beyond was a long shell of metal, empty but for heavy drifts of dust on the floor, an odd, grayish-white dust that seemed to belong among ruins undisturbed for centuries. The room looked dead like an empty skull.

She turned away, not to let them see in her face the scream of the knowledge of what that dust had been a few minutes ago.

… “Well,” said Galt, reaching for his overcoat and turning to the leader, “let’s go.”

I’ll grant this is a neat trick. It’s a genuinely suspenseful moment, which is probably why it’s one of the few passable scenes in the otherwise extremely lackluster third movie. However, it raises some larger questions.

John Galt’s capture seems anticlimactic. Ever since he appeared in this book, we’ve been told that he’s an incomparable super-genius, on an intellectual plane far above ordinary mortals. He saw the direction of the world long before anyone else did; he can come up with inventions no one else could have dreamed of. And yet when it comes to covering his tracks, he’s hapless.

He delivered his speech under his own name and made no attempt to hide or disguise his identity. When the bad guys close in on him, he’s totally unprepared. He has no escape plan: no secret tunnel into the sewers, no jet pack to blast off over the rooftops, no cloaking device like the one that hides the valley. Tony Stark was able to escape a similar predicament with a box of scraps, yet the best idea John Galt can come up with is to sit there and let himself be taken captive.

And it’s not that he had no conception he might be discovered. That’s why he rigged his lab to self-destruct. (If he has disintegrator-ray technology, why didn’t he hook it up to the front door to vaporize any unwanted guests?) It’s just that his own life and liberty don’t seem to matter to him, didn’t even occur to him as being in need of protection.

In a better-written book, this might be the author’s way of suggesting that Galt’s fatal flaw was hubris – that he was so overconfident, he never even considered that anyone else might be able to track him down. Rand doesn’t take that route, but Galt’s easy capture is a stark conflict with his consistently asserted hypercompetence. Yet again, there’s a gap between what she tells and what she shows.

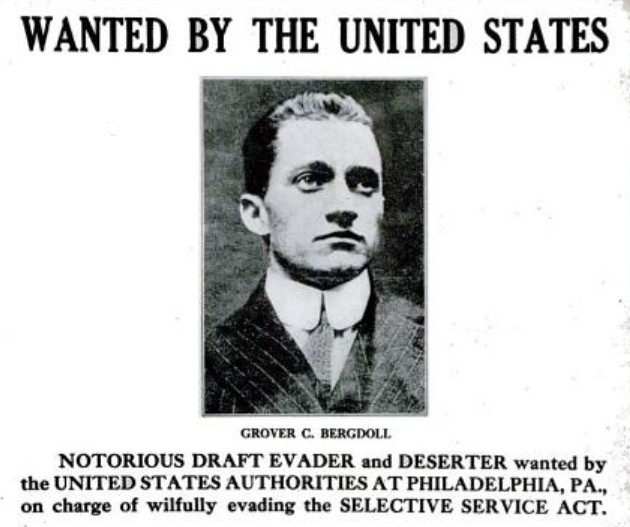

Image credit: Wikimedia Commons

Other posts in this series: