After finishing my marathon review of Atlas Shrugged, I always wanted to circle back and review Ayn Rand’s other major novel, The Fountainhead. It was part curiosity, part completionism. (An unkind assessment might add a hint of masochism.)

The Fountainhead is the earlier book, published in 1943, fourteen years before Atlas. While it was successful in its own right and helped establish Ayn Rand as an author, it’s not as well-known. This may be because, unlike Atlas Shrugged, it’s set in a specific historical period – New York in the 1920s. That means it takes place during the Great Depression, which has plot implications we’ll come to. But it also makes the novel seem dated to modern audiences, since we can look back and see that the dystopian future Rand feared never came to pass.

It’s also a work of smaller scope. Where Atlas Shrugged was ultimately about the fate of the whole world, The Fountainhead is about the lives of just four main characters. It has no greater ambition than to chronicle their doings, their triumphs and their setbacks, and it’s only concerned with what’s going on in the wider world insofar as it affects them. Like a story set in a snowglobe, nearly all the action takes place in New York City and its environs, with barely a passing glance at anything outside that region.

It’s also less triumphalist. There’s a surprisingly downbeat ending, which implies that the hero’s victory is only temporary and that the forces of socialism are tightening their grip. It’s not hard to guess that Atlas was written to correct this and provide a more satisfying comeuppance in which all bad guys everywhere get what’s coming to them.

Most important for our purposes, The Fountainhead is a glimpse of Ayn Rand’s philosophy at an earlier, less-developed stage – even though Rand denied this. In the foreword to my copy, which is a reissued anniversary edition, she insisted:

I have been asked whether I have changed in these past twenty-five years. No, I am the same — only more so. Have my ideas changed? No, my fundamental convictions, my view of life and of man, have never changed, from as far back as I can remember…

But the textual evidence contradicts this. Considered as philosophy, The Fountainhead shows clear signs of evolution when compared to Atlas. It’s less concerned with economics and politics than it is with artistic purity. It’s enamored with the romantic notion of pursuing your own vision and refusing to compromise no matter the cost, but it seems less concerned with what that vision is. In one crucial scene, the hero agrees to – gasp! – design a public housing project for the poor. That heresy would have gotten him anathematized from Galt’s Gulch.

It’s also softer on religion. Although the hero is an atheist, he – double gasp! – agrees when another character describes him as a profoundly religious man in his own way. In the novel’s crowning dramatic speech, he even implies that religious ideas are the product of human reason:

“From this simplest necessity to the highest religious abstraction, from the wheel to the skyscraper, everything we are and everything we have comes from a single attribute of man — the function of his reasoning mind.”

Again, Rand abrogated this in the foreword to my edition, claiming that she only meant this to refer to “man’s code of values”, which is a domain that should be secular but has been usurped by religion. I think it’s more likely that she wrote it when her convictions about religion weren’t so firmly fixed. By the time she came to regret it, the book was sufficiently well known that changing the text would have provoked comment and would have been seen as an admission of error.

But while The Fountainhead is more primitive, it has its moments of pure Ayn Rand. We’ll talk about its infamous rape scene, which packs more violent sexism into a few pages than there is in all of Atlas Shrugged. We’ll talk about its Nietzschean disdain for the masses of humanity, including an enthusiasm for eugenics that was left out of Rand’s later work. (Hmm, I wonder what might have happened in the interim.) We’ll examine its fanatic’s insistence that violence is a proper response to an argument you can’t refute and that terrorism is a righteous deed in the service of artistic integrity.

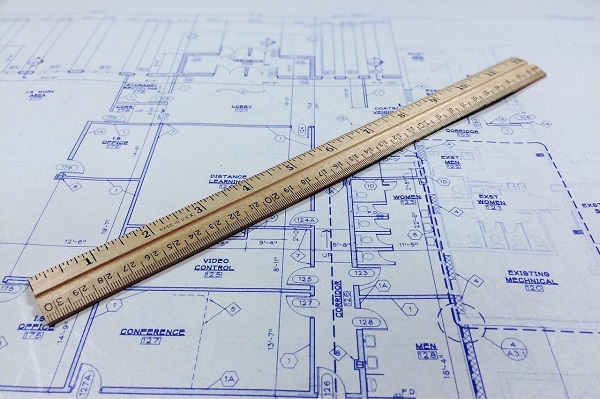

Most of all, we’ll talk about architecture, since that’s the profession of the hero. But it’s more than just a job: in this book, architecture is Serious Business. Architecture critics bestride the earth like giants, with an adoring public hanging on their every word; architects are treated like celebrities and breathlessly covered by gossip columnists and paparazzi; the latest architectural fads are the subject of front-page stories on every newspaper in the country.

In this fictional world, architecture is a language that everyone speaks. Just by looking at a building, you can tell the entire life philosophy of the person who designed it. That’s slightly less ridiculous than it sounds (but only slightly) because, as in Atlas, there are only two worldviews, Good and Evil, and everyone knows which side everyone else is on and which side they themselves are on.

We’ll use The Fountainhead‘s obsession with the building trades as a jumping-off point to branch into a discussion of housing and property. We’ll talk about urban decay and urban revival, about white flight and black migration, about redlining and restrictive covenants, about zoning and rent control, about suburbs and exurbs, about slums and gentrification. We’ll talk about cities, their history and their evolution, and what it means that humanity is now a majority-urban species. In the aftermath of a once-in-a-generation real-estate bubble and crash, this will all be timely.

And who knows, Cobra Commander may even make an appearance.

Next week, we begin with the opening scene where we meet The Fountainhead‘s protagonist, Howard Roark. Don’t miss it!

Other posts in this series: