The Fountainhead, part 1, chapter 9

First up, some good news to finish out the week: The excellent blog McMansion Hell, which I’ve mentioned in this series, was served with a legal threat by the real-estate website Zillow for using its pictures. This was obvious empty bluster, not just because parody and commentary are the essence of fair use, but because Zillow doesn’t even hold the copyright to the photos on its site, which are taken by local real-estate agents.

Kate Wagner, McMansion Hell’s creator, sent a strong response with help from the Electronic Frontier Foundation, and this week, Zillow bowed to the inevitable and retracted their demands. Score one for free speech!

The strike from last week’s installment has been settled – in whose favor, we’re not told – and construction resumes in New York. Peter Keating is feeling mightily pleased with himself, but his boss Guy Francon seems anxious and stressed, and one day he finds out why when he spies a stranger at the office:

A young woman stood before the railing, speaking to the reception clerk. Her slender body seemed out of all scale in relation to a normal human body; its lines were so long, so fragile, so exaggerated that she looked like a stylized drawing of a woman… She had gray eyes that were not ovals, but two long, rectangular cuts edged by parallel lines of lashes; she had an air of cold serenity and an exquisitely vicious mouth. Her face, her pale gold hair, her suit seemed to have no color, but only a hint, just on the verge of the reality of color, making the full reality seem vulgar.

… “I’ll see him now, if I see him at all,” she was saying to the reception clerk. “He asked me to come and this is the only time I have.”

Keating is struck speechless by her beauty. But when she’s buzzed into Guy Francon’s office and happens to glance at him as she walks past, he gets a shock. Her gaze unsettles him in a way that reminded me of Rand’s first description of Lillian Rearden:

The young woman turned and looked at Keating as she passed him on her way to the stairs. Her eyes went past him without stopping. Something ebbed from his stunned admiration. He had had time to see her eyes; they seemed weary and a little contemptuous, but they left him with a sense of cold cruelty.

Impressed and a little intimidated, he asks the clerk and finds out that the woman is Dominique Francon – the boss’s daughter. She’s the woman Guy refused to talk about. He’s eager to learn more about her, but the clerk tells him he’d better read her column in that day’s paper before he fawns over her too much:

He sent a boy for a copy of the Banner, and turned anxiously to the column, “Your House,” by Dominique Francon. He had heard that she’d been quite successful lately with descriptions of the homes of prominent New Yorkers. Her field was confined to home decoration, but she ventured occasionally into architectural criticism. Today her subject was the new residence of Mr. and Mrs. Dale Ainsworth on Riverside Drive.

This is a house that Guy Francon was commissioned to build. Peter Keating did most of the design work himself. In spite of this, Dominique’s whole column is devoted to mocking the house and its decor, damning it with faint praise while implying that its inhabitants have garishly bad taste:

“You enter a magnificent lobby of golden marble and you think that this is the City Hall or the Main Post Office, but it isn’t. It has, however, everything: the mezzanine with the colonnade and the stairway with a goitre and the cartouches in the form of looped leather belts. Only it’s not leather, it’s marble. The dining room has a splendid bronze gate, placed by mistake on the ceiling, in the shape of a trellis entwined with fresh bronze grapes. There are dead ducks and rabbits hanging on the wall panels, in bouquets of carrots, petunias and string beans. I do not think these would have been very attractive if real, but since they are bad plaster imitations, it is all right… The bedroom windows face a brick wall, not a very neat wall, but nobody needs to see the bedrooms… Tomorrow, we shall visit the home of Mr. and Mrs. Smythe-Pickering.”

Keating had designed the house. But he could not help chuckling through his fury when he thought of what Francon must have felt reading this, and of how Francon was going to face Mrs. Dale Ainsworth.

I just have to ask: if Dominique Francon trashes all the houses she writes about, how does she expect to keep getting invited to tour them? It seems like this would be a problem for the future viability of her column.

In any case, Dominique is the only female character in The Fountainhead – as always, the majority of Rand’s cast are manly men doing man-things, like sweating, swinging hammers, and smoking in armchairs with furrowed brows – so it behooves us to understand her. You might guess that she has some grudge against her father which she expresses by trashing his company’s work. But it’s not as simple as that.

Dominique is a contrary and difficult character. In some ways, she’s the stereotypical perverse woman – though maybe not to the extent of, say, praising railroads as an example of what a laissez-faire individualist can accomplish, or describing coal mining as a safe and sanitary career if not for government regulation – but perverse nevertheless. She praises failure and mediocrity and seeks to destroy whatever she genuinely respects. Rand once called Dominique “myself in a bad mood” [Anne Heller, Ayn Rand and the World She Made, p.113].

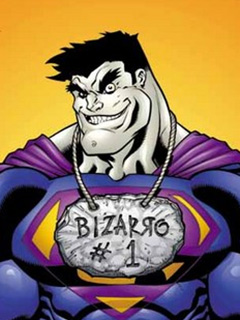

The key to understanding Dominique is that she’s a Bizarro version of Ayn Rand. She holds all the same beliefs as her creator and every other Randian hero, except for one crucial difference which causes her to arrive at all the opposite conclusions. Here’s how ex-Objectivist Barbara Branden described her:

Ayn arrived at the essence of the inner conflict that would set Dominique in opposition to Roark, by introspection… She projected what she herself felt in moments of disgust or depression, during the worst of her indignation against injustice, her contempt for depravity, her passionate rebellion against the rule of mediocrity — and asked herself: “What if I really believed that that is all there is in life, that values and heroes have no chance in the world?” What if she believed that the “journalistic” facts around her were metaphysical — necessary and unalterable by the nature of reality? Thus she projected the psychology of a woman who is motivated by the bitter conviction that values and greatness have no chance among men and are doomed to destruction — a woman who is stopped and paralyzed by contempt — a woman who withdraws from the world because of the intensity of her idealism — a woman who fights against the man she loves in order to make him renounce his career before his inevitable destruction.

It’s not hard to guess that it will be Howard Roark’s destiny to cure her cynicism with the power of his penis. (Anne Heller again: “…it is through him that Dominique will find her own real, passionate, active self, a somewhat second-handed strategy that is somehow all right for the novel’s heroine though not for the novel’s men” [p.113]).

I give Rand credit for at least trying to do something interesting with this character. It’s a fumbling stab at moral complexity, something she had long since given up on by the time she wrote Atlas Shrugged. Even so, she was restricted by the fundamentally limited nature of her imagination. She could never conceive of a human being whose opinions were truly unlike hers. Instead, she could only write antagonists whose value systems represented a mirror-image or opposite of her beliefs. Dominique Francon’s negative-image Objectivism is a little more interesting than the standard anti-Objectivism of the villains, but ultimately, no exception to this trend.

Image credit: Keoni Cabral, released under CC BY 2.0 license

Other posts in this series: