The Fountainhead, part 1, chapter 9

Ayn Rand wasn’t one for understatement. When she had a political point to make, she did it with all the subtlety of a big brass band. This makes it all the more noteworthy when she lets a controversial topic pass without comment. And one of those silences, the topic of today’s post, is a surprising one.

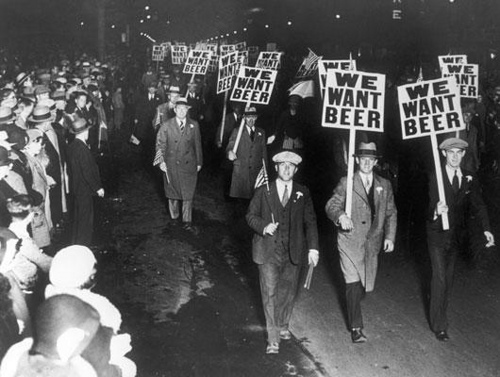

It begins with the city’s construction workers going on strike:

The strike of the building-trades unions infuriated Guy Francon. The strike had started against the contractors who were erecting the Noyes-Belmont Hotel, and had spread to all the new structures of the city. It had been mentioned in the press that the architects of the Noyes-Belmont were the firm of Francon & Heyer.

Through some plot machinations that aren’t important, Peter Keating attends a public meeting of the strikers and their supporters. The first speaker is a man named Austen Heller:

Keating looked up at the loud-speaker with a certain respect, which he felt for all famous names. He had not read much of Austen Heller, but he knew that Heller was the star columnist of the Chronicle, a brilliant, independent newspaper… that Heller came from an old, distinguished family and had graduated from Oxford; that he had started as a literary critic and ended by becoming a quiet fiend devoted to the destruction of all forms of compulsion, private or public, in heaven or on earth; that he had been cursed by preachers, bankers, club-women and labor organizers; that he had better manners than the social elite whom he usually mocked, and a tougher constitution than the laborers whom he usually defended; that he could discuss the latest play on Broadway, medieval poetry or international finance; that he never donated to charity, but spent more of his own money than he could afford, on defending political prisoners anywhere.

For an Ayn Rand protagonist, Austen Heller is unusual. He went to Oxford – even though Randian heroes usually scorn higher education – and is cultured and sophisticated – even though Randian heroes are usually aggressively uninterested in culture. You’d almost think him a villain, but he’s unquestionably on the side she considers right:

“…and we must consider,” Austen Heller was saying unemotionally, “that since — unfortunately — we are forced to live together, the most important thing for us to remember is that the only way in which we can have any law at all is to have as little of it as possible. I see no ethical standard to which to measure the whole unethical conception of a State, except in the amount of time, of thought, of money, of effort and of obedience, which a society extorts from its every member. Its value and its civilization are in inverse ratio to that extortion. There is no conceivable law by which a man can be forced to work on any terms except those he chooses to set. There is no conceivable law to prevent him from setting them — just as there is none to force his employer to accept them. The freedom to agree or disagree is the foundation of our kind of society — and the freedom to strike is a part of it.”

I love that thrown-in “unfortunately”. He hates having to see or interact with other human beings. If only we could each have our own desert island, this would be a perfect Objectivist world.

But more importantly: Austen Heller, the libertarian, supports the workers’ strike! That’s surprising by itself, but what’s more surprising still is who he’s there in company with.

The next speaker is Ellsworth Toohey, who’s somehow a celebrity to this crowd even though he hasn’t done much other than write a book about the history of architecture. The mere announcement of his name gets thunderous applause:

“Ladies and gentlemen, I have the great honor of presenting to you now Mr. Ellsworth Monkton Toohey!”

…He knew only the shock, at first; a distinct, conscious second was gone before he realized what it was and that it was applause. It was such a crash of applause that he waited for the loud-speaker to explode; it went on and on and on, pressing against the walls of the lobby, and he thought he could feel the walls buckling out to the street.

When Toohey finally speaks, Rand tells us, he holds the crowd spellbound with his oratory (because the devil has a silver tongue):

“…and so, my friends,” the voice was saying, “the lesson to be learned from our tragic struggle is the lesson of unity. We shall unite or we shall be defeated. Our will — the will of the disinherited, the forgotten, the oppressed — shall weld us into a solid bulwark, with a common faith and a common goal. This is the time for every man to renounce the thoughts of his petty little problems, of gain, of comfort, of self-gratification. This is the time to merge his self in a great current, in the rising tide which is approaching to sweep us all, willing or unwilling, into the future. History, my friends, does not ask questions or acquiescence. It is irrevocable, as the voice of the masses that determine it. Let us listen to the call. Let us organize, my brothers. Let us organize.”

All Rand characters wear their politics on their sleeves, and this talk of “renouncing self-gratification” or “the voice of the masses” is a sure giveaway of a villain. But this leads into a fascinating contradiction.

As we’ll see shortly, Austen Heller will become one of Roark’s few friends and also the man who gives him his first and most important commission. Clearly, he’s on the side Rand expects us to agree with. On the other hand, Ellsworth Toohey is an insidious advocate of collectivism. As a rule, whenever such a character says something in an Ayn Rand novel, we’re supposed to boo and hiss. But Heller and Toohey both support the strike!

For a reader of Rand’s oeuvre, this is disorienting. Normally, every moral issue in her books is binary black and white, with the good guys and the villains lining up on equal and opposite sides. To have a fearless individualist and a soulless socialist on the same side of a political debate is something I can’t recall seeing anywhere else in all her writing.

The only way I can explain this is as a particularly glaring example of how Rand’s views changed and hardened. It seems likely that when she wrote The Fountainhead, she didn’t view labor organizing as an important political issue. She saw nothing untoward in having both heroes and villains support unions, each for their own reasons. (Later in the book, we’ll see another “good” character give an endorsement of collective bargaining.)

By the time she wrote Atlas Shrugged, this had changed. In that book, labor unions are another tentacle of the socialist octopus, and their only purpose is to impede heroic businessmen from doing what they want to do.

Of course, there’s nothing inherently bad or unusual about a person’s opinions changing over time. It happens to all of us. The evolution of Rand’s view on unions is worth noting only because she insisted it never happened, that she was ideologically flawless from the beginning and stayed that way throughout her life. But her own writing testifies to the contrary.

Image credit: Tony Werman, released under CC BY 2.0 license

Other posts in this series: