The Fountainhead, part 1, chapter 12

The Wynand newspaper chain, trying to boost its sales and publicity, decides to run an exposé of living conditions in New York’s slums. The editor-in-chief Alvah Scarret assigns Dominique Francon, who’s his favorite columnist, to do an investigation. Although Dominique is used to living in the lap of luxury, she agrees to spend two weeks living in a run-down tenement on the East Side, washing up in a tin bath, peeling potatoes in a shared kitchen, mingling with the poor people who live there and getting to know them.

At the end of two weeks she returned to her penthouse apartment on the roof of a hotel over Central Park, and her articles on life in the slums appeared in the Banner. They were a merciless, brilliant account.

She heard baffled questions at a dinner party. “My dear, you didn’t actually write those things?”

“Dominique, you didn’t really live in that place?”

“Oh, yes,” she answered. “The house you own on East Twelfth Street, Mrs. Palmer,” she said, her hand circling lazily from under the cuff of an emerald bracelet too broad and heavy for her thin wrist, “has a sewer that gets clogged every other day and runs over, all through the courtyard. It looks blue and purple in the sun, like a rainbow.”

“The block you control for the Claridge estate, Mr. Brooks, has the most attractive stalactites growing on all the ceilings,” she said, her golden head leaning to her corsage of white gardenias with drops of water sparkling on the lusterless petals.

Alvah Scarret thinks Dominique’s muckraking is going to be a huge hit. In a bid to squeeze more news out of it, he sends her out to speak on what she found so the Banner can cover her speech. But:

She was asked to speak at a meeting of social workers. It was an important meeting, with a militant, radical mood, led by some of the most prominent women in the field… She stood in the speaker’s pulpit of an unaired hall and looked at a flat sheet of faces, faces lecherously eager with the sense of their own virtue. She spoke evenly, without inflection. She said, among many other things: “The family on the first floor rear do not bother to pay their rent, and the children cannot go to school for lack of clothes. The father has a charge account at a corner speak-easy. He is in good health and has a good job… The couple on the second floor have just purchased a radio for sixty-nine dollars and ninety-five cents cash. In the fourth floor front, the father of the family has not done a whole day’s work in his life, and does not intend to. There are nine children, supported by the local parish. There is a tenth one on its way…” When she finished there were a few claps of angry applause. She raised her hand and said: “You don’t have to applaud. I don’t expect it.”

As with the section on unions, here we see Rand’s political views in an earlier, less evolved form. Already present is her trademark scorn for social reformers (“lecherously eager with the sense of their own virtue”) – and, especially, her scorn for the poor. In the Ayn Rand worldview, hard work is always rewarded with wealth and success. The only people trapped in poverty are the lazy, shiftless ones who refuse to better themselves.

But the interesting thing is that she doesn’t stint from criticizing rich landlords either. In fact, Dominique mocks them for their attitude of neglect, raking in the rent while allowing their tenants to live in squalor. (When Dominique is challenged about why she gave those speeches to those audiences, she says, “They’re true, though, both sides of it, aren’t they?”)

By the time she wrote Atlas Shrugged, her opinion had changed. In that book, as long as you didn’t make money by working for the government, she held that to be rich was by definition to be virtuous. She held that the rich were above puny mortal standards of good and evil. She even cheered one of her protagonists for building a shoddy, death-trap housing project for his workers, the very sin that’s condemned here. It’s tempting to guess that the shift in attitude came about because when she wrote The Fountainhead, she wasn’t yet wealthy or successful herself.

If Dominique hadn’t spiked her own story, it’s not unrealistic that it would have been a hit. Poverty porn has always been popular, going back to the first muckrakers.

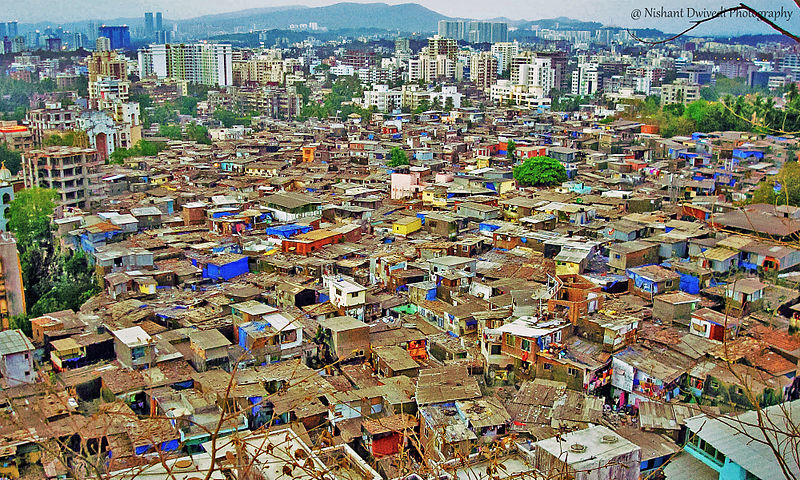

From Rio de Janeiro’s notorious and colorful favelas (which were variously bulldozed and walled off from Olympic dignitaries), to the urban shantytowns of African capitals like Freetown in Sierra Leone, to India’s vast slums like the Dharavi neighborhood of Mumbai, we love to gawk at slum dwellers, to read about their lives with mingled fascination and pity. In all these places, tens of millions of people live in appalling conditions of crowding and poverty:

A walk through Dharavi is a journey through a dank maze of ever-narrowing passages until the shanties press together so tightly that daylight barely reaches the footpaths below, as if the slum were a great urban rain forest, covered by a canopy of smoke and sheet metal.

Traffic bleats. Flies and mosquitoes settle on roadside carts of fruit and atop the hides of wandering goats. Ten families share a single water tap, with water flowing through the pipes for less than three hours every day, enough time for everyone to fill a cistern or two. Toilets are communal, with a charge of 3 cents to defecate. Sewage flows through narrow, open channels, slow-moving streams of green water and garbage.

It’s not wrong to say that life in slums is dirty, hardscrabble, brutish and often short. Clean water is a precious commodity. Sewage flows through the streets; garbage piles up; diseases like tuberculosis and cholera run rampant in crowded, dirty conditions. Privacy is nonexistent: families sleep eight or ten to a room in scorching tropical heat, sometimes without beds or blankets; washing and defecating has to be done in public. Houses patched together from makeshift materials can collapse without warning. Extreme poverty, earning less than $1 per day, is the norm. Crime and gangs are a perpetual threat.

And yet, contrary to Rand’s view (and, to be fair, many people besides Ayn Rand believe this), it’s not the whole story to say that slums are miserable hellholes where people dwell only because they have no choice. The fact is that tens of millions of people around the world choose to live in slums, and the reason is simple: economic opportunity.

Slum communities are often the best places for the very poor to earn money. As bad as they can be, they tend to have more jobs and better wages than in the rural countryside. Dharavi, for example, has a bustling economy in a broad range of industries – leatherwork, garment making, pottery, recycling – with annual output estimated at $1 billion. Their products are exported all over the world. Some migrants come there to learn skills they can take back to start their own businesses in other slums, as if it were a franchise. As this article notes, it even has its own self-made millionaires.

As this site puts it:

As these businesses continue to expand, Dharavi has become a community linked and supported by entrepreneurship. The local businesses are providing small but significant income improvements to tens of thousands of families. Electricity, running water and televisions are now available to an increasing number of households.

India has tried to relocate slum dwellers, only to have them come back because, crowded and unsanitary as they are, they’re the best place to find jobs. Brazil’s favelas, too, generate billions of dollars in economic activity, and a surprisingly large percentage of their residents are middle class.

This is the same evolution that the U.S. went through with its slums and sweatshops, as chronicled by early muckrakers like Jacob Riis. As bad as lives and working conditions were in those places – and make no mistake, they’re usually very bad – they’re also, paradoxically, a vital stepping stone to opportunity. Slum dwellers all over the world aren’t trapped or lazy or ignorant, they’re making rational decisions given the choices that are available to them. They don’t need to be relocated for their own good. What they need are services: reliable electricity, clean drinking water, sanitation to prevent outbreaks of disease, and legal title to their land so they can’t be displaced.

Image: Slums in Mumbai, via Nishantd85; released under CC BY-SA 3.0 license

Other posts in this series: