The Fountainhead, part 1, chapter 15

Down to his last few dollars, with rent overdue and unpaid bills piling up, Roark gets a last-minute reprieve. A big, important commission has come his way from the Manhattan Bank Company, thanks to an ally on the board of directors who admires his work. He’s been waiting for days for a definite yes-or-no answer, and finally the telephone rings and they ask him to come to their office:

The chairman of the board was waiting for him in his office, with Weidler and with the vice-president of the Manhattan Bank Company. There was a long conference table in the room, and Roark’s drawings were spread upon it. Weidler rose when he entered and walked to meet him, his hand outstretched. It was in the air of the room, like an overture to the words Weidler uttered, and Roark was not certain of the moment when he heard them, because he thought he had heard them the instant he entered.

“Well, Mr. Roark, the commission’s yours,” said Weidler.

They’re planning a skyscraper in the heart of Manhattan, the greatest building Roark has ever had a chance to design. He barely hears the rest of what they’re saying, since he’s already imagining “the first bite of machine into earth that begins an excavation”. He’s as close to openly happy as he ever gets in this novel. Then the chairman says that they have one small condition:

He pulled a sketch from under the drawings on the table and handed it to Roark.

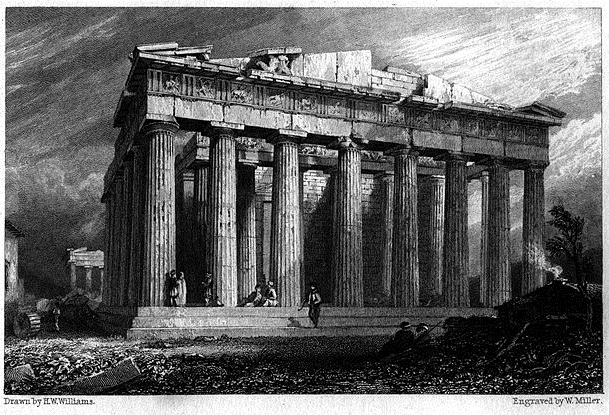

It was Roark’s building on the sketch, very neatly drawn. It was his building, but it had a simplified Doric portico in front, a cornice on top, and his ornament was replaced by a stylized Greek ornament.

Basically, they added one of these. (Insert horrified gasp here.)

The bank’s owners aren’t just insisting on Classic elements because they’re evil socialists muahaha. They make a very reasonable argument for why they want these changes:

“You see the point?” said the chairman soothingly. “Our conservatives simply refused to accept a queer stark building like yours. And they claim that the public won’t accept it either. So we hit upon the middle course. In this way, though it’s not traditional architecture of course, it will give the public the impression of what they’re accustomed to. It adds a certain air of sound, stable dignity — and that’s what we want in a bank, isn’t it? It does seem to be an unwritten law that a bank must have a Classic portico — and a bank is not exactly the right institution to parade law-breaking and rebellion.”

What they’re saying is that architecture, like fashion, is a language. The appearance of a building communicates the designer’s intent, whether it’s a glass-and-steel skyscraper, an elaborately carved medieval cathedral, or a suburban house with a green lawn and a white picket fence. Each says something different about how the people who live and work there want to be perceived by the world.

In this context, the board’s request makes sense. Using ancient styles conveys a message of stability and permanence, which is what you want in a bank. When people are deciding where to store their life savings, the last thing you want is to make them think that you’re a radical innovator or a risk-taker.

And again, despite Ayn Rand’s insistence that the world hates Roark for his greatness, her own text shows people going out of their way to be reasonable to him. The board members say that they like everything else about his design, including “the logic of the plan”. They also say that this sketch is only a concept and they don’t expect him to follow it slavishly, but that he can make his own adaptation of the Greek motif. Since Roark is on record saying that there is such a thing as “good Classic“, this ought to be no trouble.

So naturally, he refuses:

He spoke for a long time. He explained why this structure could not have a Classic motive on its facade. He explained why an honest building, like an honest man, had to be of one piece and one faith; what constituted the life source, the idea in any existing thing or creature, and why — if one smallest part committed treason to that idea — the thing of the creature was dead; and why the good, the high and the noble on earth was only that which kept its integrity.

Yeah, but Roark helped Peter Keating design a Renaissance-style building he was so ashamed of, he would have paid blackmail not to have his name on it. Doesn’t this mean that Roark has already surrendered his honesty and committed treason to his own sense of purpose? It shows some hypocrisy to be lecturing the board about integrity now.

The view of architecture as a language shows what’s so absurd about Roark’s stubbornness. Like any language, the combination of elements can convey an infinite variety of meanings. You can wear an expensive Rolex watch with jeans and a t-shirt, and that says one thing; wearing that same watch with a finely tailored suit says something else. The only thing that makes a combination of elements “correct” is whether they add up to the message their creator wants to send.

Roark’s insistence that Greek-inspired stylistic choices are “dishonest” makes about as much sense as saying that the words “chocolate” and “vanilla” can’t appear together in the same sentence, because he just made up a new rule of grammar that says so. In that respect, it’s similar to equally arbitrary religious dogmas, like the Old Testament law against wearing cloth of mingled fabrics.

If Roark were a lone artist working for himself, he could abide by whatever bizarre self-imposed rules he dreamed up. But, as he repeatedly fails to comprehend, he’s working for customers who are paying him to design the buildings they want. Even if the building had “integrity” according to Roark’s narrow definition, what good would that be if customers shunned it? It’s worth noting that he never rebuts the chairman’s argument that bank customers want a sense of familiarity and stability; he just refuses to consider it relevant.

What Roark really wants is to build without regard to his customers’ wants or needs. We saw that in the Sanborn house, where he scoffed at the idea of elderly relatives not being able to climb his spiral staircase, and in his repeated rejections of Austen Heller’s followers, because they didn’t want the houses he wanted to build for them.

We saw it in a different way with the Fargo store, which was in a dying neighborhood and closed down almost as soon as it opened. Most architects would be perturbed by that failure, even if it didn’t reflect directly on them; but apparently not Roark. Once the building is built according to his plan, nothing else concerns him. He seems to believe that the ideal customer would have appreciated it and that’s what matters, even if no one like that actually exists.

Roark gathered the drawings from the table, rolled them together and put them under his arm.

“It’s sheer insanity!” Weidler moaned. “I want you. We want your building. You need the commission. Do you have to be quite so fanatical and selfless about it?”

…Roark smiled. He looked down at his drawings. His elbow moved a little, pressing them to his body. He said:

“That was the most selfish thing you’ve ever seen a man do.”

Roark walks home, closes his office, and gives the keys to his landlord. Then he goes to visit his friend Mike the construction worker, tells him what happened and says he’s quitting the architectural profession. He asks Mike to help him get a job as a manual laborer, somewhere he can earn his own living and won’t have to deal with the corruption and hypocrisy of other architects who unforgivably build the buildings their clients want to buy.

Mike is outraged on Roark’s behalf, but reluctantly agrees to find him a job. He knows of a granite quarry in Connecticut, owned by a contractor who often does business with Guy Francon, that’s hiring. Two days later, Roark is on a train, heading north out of the city.

This is the end of part 1 of The Fountainhead. In a more realistic novel, Roark’s story would end here. He’s blown every chance he’s gotten, burned every bridge he’s crossed, and backstabbed every person who tried to help him. Ending up consigned to a life of manual labor is a plausible outcome. Of course, the author is on his side and will soon get him back in the game.

But before we get there, there’s a lot of ground to cover. In part 2, we’ll read more about Ellsworth Toohey the evil socialist art critic, meet another heroic Objectivist murderer, witness the spectacle of a Jewish writer with a soft spot for eugenics, and come face-to-face with the most infamously misogynist sex scene in all of Ayn Rand’s work.

Image: A portico, the sure mark of architectural evil. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Other posts in this series: