The Fountainhead, part 2, chapter 5

Dominique Francon has returned to New York. As much as she hates to admit it, she can’t get Howard Roark off her mind.

Despite what Rand wrote at the time about how traumatized she was in the aftermath of Roark’s violent sexual assault on her, Dominique has decided that she loves him and is obsessed with him. But she has no way to find him, since she never learned his name or anything about him. As far as she knows, he’s just some redhead roughneck.

She went out alone for long walks. She walked fast, her hands in the pockets of an old coat, its collar raised. She had told herself that she was not hoping to meet him. She was not looking for him. But she had to be out in the streets, blank, purposeless, for hours at a time.

A few days after she returns to work, Ellsworth Toohey walks into her office at the Banner. They exchange pleasantries – he claims to be a “great admirer” of hers, while she calls him “the most comforting person I know”. They get to talking over a picture of Roark’s Enright House, the same one mentioned earlier:

On the desk before her lay the rotogravure section of the Sunday Chronicle. It was folded on the page that bore the drawing of the Enright House. She picked it up and held it out to him, her eyes narrowed in a silent question. He looked at the drawing, then his glance moved to her face and returned to the drawing. He let the paper drop back on the desk.

“As independent as an insult, isn’t it?” he said.

“You know, Ellsworth, I think the man who designed this should have committed suicide. A man who can conceive a thing as beautiful as this should never allow it to be erected. He should not want to exist. But he will let it be built, so that women will hang out diapers on his terraces, so that men will spit on his stairways and draw dirty pictures on his walls. He’s given it to them and he’s made it part of them, part of everything. He shouldn’t have offered it for men like you to look at. For men like you to talk about. He’s defiled his own work by the first word you’ll utter about it. He’s made himself worse than you are. You’ll be committing only a mean little indecency, but he’s committed a sacrilege. A man who knows what he must have known to produce this should not have been able to remain alive.”

As I’ve said before, Dominique is a bizarro version of Ayn Rand herself, holding all the right beliefs save one. Obviously, Rand doesn’t share Dominique’s view that Howard Roark should have committed suicide rather than give his beautiful buildings to an unappreciative world. But I wonder which part of this, specifically, we’re supposed to disagree with.

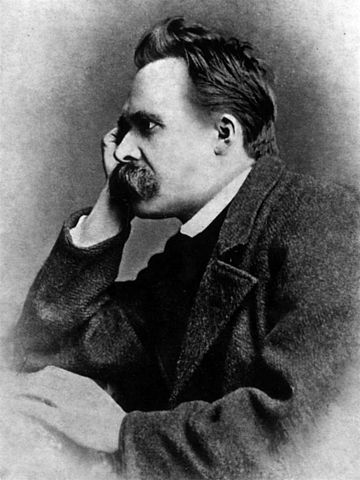

This book demonstrates over and over again that Rand doesn’t disagree with Dominique’s opinion that the vast majority of people are wretched scum who are unworthy to breathe the same air as the True Creators. That Nietzschean contempt is like an echo in the background of all her books, from this one to Atlas Shrugged. In her view, a tiny handful of individuals are the only ones whose lives have value, the other 99% of us are nothing but an obstacle to their greatness, and it’s only by a wholly undeserved grace that they don’t blast us all off the earth.

I think we’re meant to conclude that what Dominique got wrong is that, out of all the teeming masses, there are just enough second-tier individuals who appreciate the True Creators’ talent to make their effort worthwhile. These are people like Austen Heller in this novel, or Eddie Willers in Atlas: the ones who bestow upon the heroes the flattery and worship that they deserve. In fact, Dominique herself will become such a person near the end of the book, when she gives in and becomes the adoring helpmeet that Howard Roark deserves by right. Possibly, her error is not realizing where she herself fits into Rand’s strict hierarchy of human worthiness.

There’s a very short scene in this chapter in which Steven Mallory, the sculptor, goes on trial for his attempted murder of Ellsworth Toohey. To everyone’s surprise, Toohey shows up in court – as a witness for the defense:

At his trial for the assault on Ellsworth Toohey, Steven Mallory refused to disclose his motive. He made no statement. He seemed indifferent to any possible sentence. But Ellsworth Toohey created a minor sensation when he appeared, unsolicited, in Mallory’s defense. He pleaded with the judge for leniency; he explained that he had no desire to see Mallory’s future and career destroyed. Everybody in the courtroom was touched — except Steven Mallory. Steven Mallory listened and looked as if he were enduring some special process of cruelty. The judge gave him two years and suspended the sentence.

This gesture of mercy is supposed to cement Toohey’s status as a villain, since “forgiveness” is a dirty word as far as Ayn Rand is concerned. (There’s a part near the end of the novel when Dominique says about another character, “Have a little pity on him,” and Roark responds, “Don’t speak their language.”)

Later in this chapter, Dominique meets up with Peter Keating, but he notices something different about her. She doesn’t reject him or turn away from him, but he nevertheless senses in her a feeling of “revulsion, so great that it became impersonal, it could not offend him, it seemed to include more than his person.” He correctly guesses that she’s thinking of someone else, someone who matters tremendously to her:

“Dominique, who was he?”

She whirled to face him. Then he saw her eyes narrowing. He saw her lips relaxing, growing fuller, softer, her mouth lengthening slowly into a faint smile, without opening. She answered, looking straight at him:

“A workman in the granite quarry.”

She succeeded; he laughed aloud.

“Serves me right, Dominique. I shouldn’t suspect the impossible.”

Dominique says she used to think she could eventually come to care about him, but she’s disillusioned of that belief now:

“Peter, isn’t it strange? It was you that I thought I could make myself want, at one time.”

“Why is that strange?”

“Only in thinking how little we know about ourselves. Some day you’ll know the truth about yourself too, Peter, and it will be worse for you than for most of us. But you don’t have to think about it. It won’t come for a long time.”

“You did want me, Dominique?”

“I thought I could never want anything and you suited that so well.”

OK, that was a sick burn.

Although it’s a good line, it further emphasizes how little most people matter according to Objectivism. As far as Rand is concerned, Keating and all average people are nobodies, in the literal sense of the word. They might as well not exist. They can be brushed aside, like paper cutouts.

It’s only a tiny minority of people who matter or whose humanity ought to be taken into account. Like any good con, the book invites its readers to think of themselves as belonging to that privileged elite merely by virtue of having read it. The reality is that Ayn Rand would surely have been disgusted with all of them if they’d ever met her, the same way she ended up disgusted with almost all her contemporary followers. When you idealize humanity to such an extent as to treat impossible, untouchable fictional geniuses as the only human beings worthy of the name, it’s no surprise that flesh-and-blood people, with their failings and their foibles, tend not to measure up.

Image credit: Wikimedia Commons

Other posts in this series: