The Fountainhead, part 2, chapter 6

Last week, we read about Howard Roark attending a black-tie ball where he knew Dominique would be present, just to torture her with the sight of him. While Roark is working the crowd, we see – further undermining the author’s insistence that the world hates her hero for his greatness – that most of the people at the party are friendly and cordial to him:

Roark was introduced to many people and many people spoke to him. They smiled and seemed sincere in their efforts to approach him as a friend, to express appreciation, to display good will and cordial interest. But what he heard was: “The Enright House is magnificent. It’s almost as good as the Cosmo-Slotnick Building.”

“I’m sure you have a great future, Mr. Roark, believe me, I know the signs, you’ll be another Ralston Holcombe.” He was accustomed to hostility; this kind of benevolence was more offensive than hostility.

Roark considers praise an insult, if the substance of the praise isn’t that he’s the best architect ever. Any lesser compliment, to him, is intolerable rudeness. This massive arrogance doesn’t seem to register with Ayn Rand as such, possibly because she felt the same way herself and thought of it as a perfectly normal, unremarkable attitude.

Ellsworth Toohey is also at the party, but he’s avoiding Roark, despite being “abnormally aware” of his presence. While he’s smiling and chatting with his friends, he can’t stop glancing at the man with the orange hair:

He did not know the man’s name, his profession or his past; he had no need to know; it was not a man to him, but only a force; Toohey never saw men. Perhaps it was the fascination of seeing that particular force so explicitly personified in a human body.

When he gives in and asks a friend who that person is, and is told that it’s Howard Roark, builder of the Enright House, Toohey is unsurprised (“Of course. It would be”).

Notice, Toohey’s reaction isn’t “So that’s what he looks like.” As soon as he hears the name, it’s as if he had a hypothesis confirmed. He was expecting Roark to look the way he does.

I’ve often said that Rand’s characters aren’t people so much as philosophical principles incarnated, but this chapter makes it literal. According to the villain, Roark is a “a force… personified in a human body”. And like the elementals of high fantasy, that force shapes the body it inhabits.

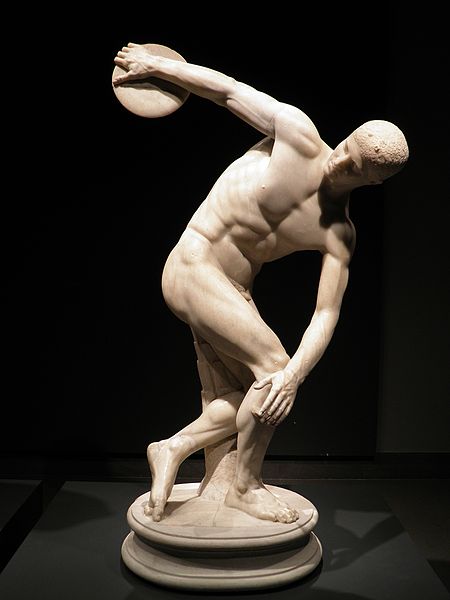

Howard Roark, in his author’s eyes, could never have been a short, pot-bellied man with thinning hair. In Rand’s world, all fearless individuals have the same appearance: tall, thin, athletically muscular with an angular face, like the Greek sculpture of the discus thrower (blue eyes and blond hair optional, but recommended). They’re all alike as if cast in the same mold. And the more closely they approach this physical ideal, the more fearless and individualistic they must be.

Her villains have a bit more variety, but the same principle holds true for them. They can be frail, big-headed intellectuals like Ellsworth Toohey, or rotund, jowly men like in Atlas Shrugged. Although it’s rarer, they can also be handsome like Peter Keating or Lillian Rearden in Atlas, in a the-devil-hath-power-to-assume-a-pleasing-shape kind of way.

It seems as if Toohey has figured out this categorization scheme, and so he knows everything he needs to know about someone just by getting a glimpse at them. This is an unusual degree of awareness for a Rand villain, arguably fourth-wall-breaking.

And it’s not just some idiosyncrasy of Toohey’s to view people this way. Rand considers it a glimpse into an underlying reality. Later that evening, as the party is winding down, the hostess asks Dominique what she thinks of the new kid on the block:

“And, my dear,” asked Kiki Holcombe, “what did you think of that new one, you know, I saw you talking to him, that Howard Roark?”

“I think,” said Dominique firmly, “that he is the most revolting person I’ve ever met… Do you care for that sort of unbridled arrogance? I don’t know what one could say for him, unless it’s that he’s terribly good-looking, if that matters.”

“Good-looking! Are you being funny, Dominique?”

Kiki Holcombe saw Dominique being stupidly puzzled for once. And Dominique realized that what she saw in his face, what made it the face of a god to her, was not seen by others; that it could leave them indifferent; that what she had thought to be the most obvious, inconsequential remark was, instead, a confession of something within her, some quality not shared by others.

Well, obviously. Minor characters don’t have Toohey’s level of medium awareness; they don’t know they’re in a novel where a person’s inner character maps one-to-one onto their outer appearance. As a heroic-individualist-to-be, Dominique also knows this, although she doesn’t realize she knows it.

Ellsworth Toohey overhears and joins the conversation, praising Dominique for her discernment. He says they’re more alike than she knows, and that “it was interesting to discover what sort of thing appears good-looking to you”:

“What’s the matter with both of you, Ellsworth? Why such talk — over nothing at all? People’s faces and first impressions don’t mean a thing.”

“That, my dear Kiki,” he answered, his voice soft and distant, as if he were giving an answer, not to her, but to a thought of his own, “is one of our greatest common fallacies. There’s nothing as significant as a human face. Nor as eloquent. We can never really know another person, except by our first glance at him. Because, in that glance, we know everything. Even though we’re not always wise enough to unravel the knowledge.”

In fairness, although Ayn Rand took it to ludicrous extremes, it’s not entirely unrealistic that you can learn about a person from a brief encounter. Human beings can be surprisingly good at rapidly and unconsciously inferring information about others, especially in social settings.

In one famous experiment, participants were shown a short, silent video clip – as short as 10 seconds – of a teacher giving a lecture, and were asked to rate that teacher’s competence. Those ratings tend to be similar to ratings given by students who’ve taken an entire semester of classes with that teacher. People are also better than chance at guessing someone’s sexual orientation from a brief video or even a photograph. Psychologists call this ability “thin-slicing“.

One plausible explanation for it is that, because we’re a social species, evolution has selected for the ability to quickly infer important information about strangers. It’s a useful skill if you need to know who holds the power, who’s a trustworthy confidant, whose ideas are worth listening to, or who might be sexually attracted to you. These inferences are based on subtle cues that we may not consciously pick up on, but they express themselves as intuitions or gut feelings. (Of course, a less cheery alternative is that people form assumptions about others as soon as they meet them and then refuse to let those assumptions be budged by subsequent evidence.)

Granted, this falls far short of the impossible standard of The Fountainhead where a Toohey or a Roark can discern a person’s entire soul, their darkest desires, and their most private thoughts from a momentary glimpse of their face. Thin-slicing isn’t a superpower of perception that works every time. It’s only detectable statistically, over large numbers of trials with many different people. It works better for some personality traits than others. It can be thrown off by a person’s preexisting biases and prejudices. And in individual cases, snap judgments can be horribly wrong. After all, Ted Bundy was infamously charming and charismatic.

Image credit: Carole Radatto via Wikimedia Commons; released under CC BY-SA 2.0 license

Other posts in this series: