The Fountainhead, part 2, chapter 15

After Hopton Stoddard wins his lawsuit against Howard Roark, the question is what will become of Roark’s Temple of the Human Spirit. Ellsworth Toohey persuades Stoddard to remodel the building and devote it to a new purpose, the one Toohey wanted all along: a group home for physically and intellectually disabled young people, or as the text puts it, the “Hopton Stoddard Home for Subnormal Children”.

The contrast, which we’re meant to notice, is that Roark built his temple as a monument to what humanity could be at its best, whereupon Toohey desecrates it by making it a warehouse for the lowest and least worthy specimens of humanity. (Yes, this message has the stink of eugenics all over it. We’ll get to that next week.)

Hopton Stoddard added a generous sum to the award he had won from Roark, and the Stoddard Temple was rebuilt for its new purpose by a group of architects chosen by Ellsworth Toohey: Peter Keating, Gordon L. Prescott, John Erik Snyte and somebody named Gus Webb, a boy of twenty-four who liked to utter obscenities when passing well-bred women on the street, and who had never handled an architectural commission of his own.

If Rand is implying that Gus Webb is a bad person because he’s a sexist who treats women disrespectfully, sorry, but that ship sailed long ago. You don’t get to make street harassment a badge of villainy when you cheer your protagonist for doing far worse.

Each of them had a set of photographs of the original sketches with the signature “Howard Roark” visible in the corner. They spent many evenings and many weeks, drawing their own versions right on the originals, remaking and improving. They took longer than necessary. They made more changes than required. They seemed to find pleasure in doing it.

…The Stoddard Temple was not torn down, but its framework was carved into five floors, containing dormitories, schoolrooms, infirmary, kitchen, laundry. The entrance hall was paved with colored marble, the stairways had railings of hand-wrought aluminum, the shower stalls were glass-enclosed, the recreation rooms had gold-leafed Corinthian pilasters. The huge windows were left untouched, merely crossed by floorlines.

OK, I’m confused. How big was Roark’s temple originally? The text said that it was “a small building” and “scaled to human height”. Ellsworth Toohey called it “flauntingly horizontal”, lacking the “soaring lines” and “gigantic proportions” of proper religious buildings. But this paragraph implies that there was a single, five-story-high interior space that was carved up into separate floors. That sounds pretty soaring and cathedral-like to me.

The four architects had decided to achieve an effect of harmony and therefore not to use any historical style in its pure form. Peter Keating designed the white marble semi-Doric portico that rose over the main entrance, and the Venetian balconies for which new doors were cut. John Erik Snyte designed the small semi-Gothic spire surmounted by a cross, and the bandcourses of stylized acanthus leaves which were cut into the limestone of the walls. Gordon L. Prescott designed the semi-Renaissance cornice, and the glass-enclosed terrace projecting from the third floor. Gus Webb designed a cubistic ornament to frame the original windows, and the modern neon sign on the roof, which read: “The Hopton Stoddard Home for Subnormal Children.”

…The original shape of the building remained discernible. It was not like a corpse whose fragments had been mercifully scattered; it was like a corpse hacked to pieces and reassembled.

Like an architectural Island of Dr. Moreau, Roark’s temple suffers brutal torture at the hands of these mad scientists, until it’s reborn as an ugly, Frankensteinian monstrosity.

It’s not exactly the horror show Rand wants us to think it is, but nevertheless, I felt an unexpected pang of sympathy. This chapter reminded me of something I’m all too familiar with.

New York train commuters utter the name of Manhattan’s Penn Station with dread. It’s a grimy, subterranean maze of tunnels and passageways lit by fluorescent glare, crammed with shoulder-to-shoulder crowds during rush hour, miserably hot and swampy during the summer, completely lacking in natural light and air flow. It’s been condemned in every imaginable set of terms; according to this article on the Verge, it’s been called “the worst place in New York City,” “the worst transit experience in the US,” and even “the worst place on Earth”.

There are some good reasons why Penn Station is such an eyesore. It’s the busiest passenger hub in the Western Hemisphere, serving 650,000 passengers a day, which makes it impossible to make major renovations that would put it completely out of service. Three different railroads (Amtrak, New Jersey Transit, and the Long Island Railroad) share the space and the tunnels under the Hudson and East Rivers, plus connections to several subway lines, which makes coordinating repairs nightmarishly complicated.

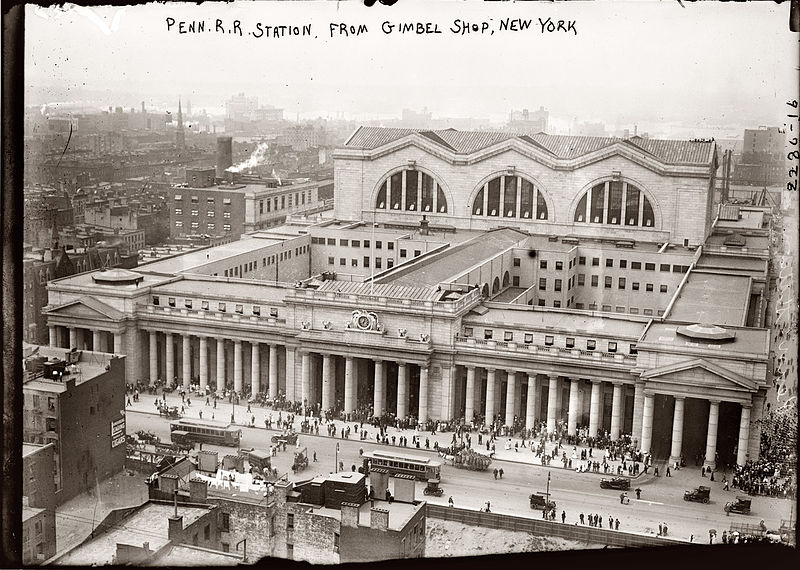

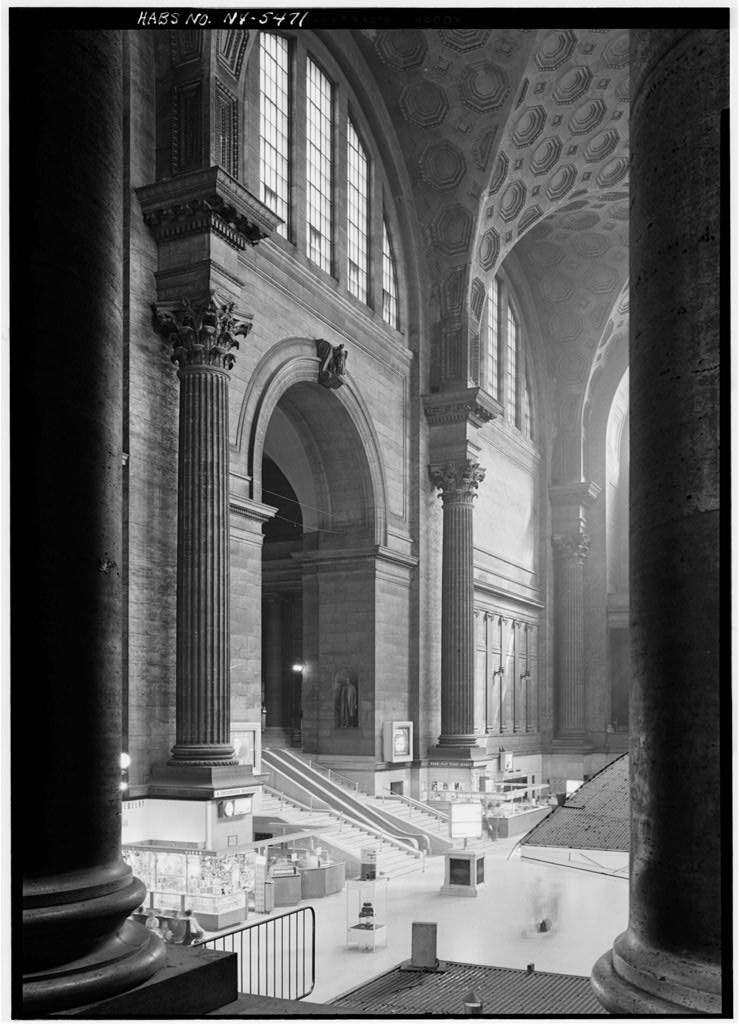

But it wasn’t always this way. The original Pennsylvania Station, which opened in 1910, was an architectural jewel of the city. Designed in the Beaux-Arts style by the renowned architectural firm McKim, Mead & White, it had a monumental granite and marble exterior, ringed with Doric columns and carved eagles. The interior hall was an immense, soaring space that echoed the Roman Baths of Caracalla, and a light-filled and airy concourse beneath an intricate roof of iron and glass led to the tracks. Seeing pictures of what it used to look like is enough to fill the most jaded New Yorker’s heart with despair:

What happened?

The old Penn Station, magnificent though it was, was expensive to maintain and seemed increasingly antiquated. By the 1950s, with ridership declining and car commuting and air travel on the rise, Pennsylvania Railroad executives were convinced that railroads were on the way out. The city had no desire to adopt the structure, fearing it would be a money pit, so the owners sold the above-ground development rights.

There were protests from modernist architects including Philip Johnson and Robert Venturi (yes, modern architects rallied to save a classical building, something that doubtless gave Ayn Rand head-exploding levels of cognitive dissonance), but few other people noticed or cared.

In 1963, the wrecking balls began to swing. Madison Square Garden rose on the spot where the old Penn Station had been, and the grand columns and other rubble were dumped in the marshlands of New Jersey. The platforms and concourses were buried underground, giving birth to the grim warren we have today. The architectural historian Vincent Scully said, in reference to the old and new Penn Stations: “One entered the city like a god; one scuttles in now like a rat.” Ironically, fears about the demise of railroads proved ill-founded, and ridership is higher than ever.

There’s just one silver lining to this cloud: after the demolition, NYC realized the magnitude of the crime against architecture that it had committed. The New York Times eulogized, “We will probably be judged not by the monuments we build but by those we have destroyed.”

It was as a direct result that, in the mid-60s, the city passed the first landmark preservation laws to save other notable buildings from Penn Station’s fate. New York City’s other iconic mass-transit hub, Grand Central Terminal, owes its survival to these laws.

And this may not be the end of the story. There are plans afoot to redevelop the site and restore Penn Station, if not to its old glory, then to a new form that’s more uplifting and aesthetically pleasing. There’s widespread agreement that Madison Square Garden has to go, and in 2013, the city gave the owners ten years to vacate the site. When their lease is up, we’ll have a free hand to rebuild Penn Station, and there have been some interesting proposals – many in the steel-and-glass modernist style, even. (Howard Roark would have approved.) From where we are now, there’s nowhere to go but up.

All images public domain, via Library of Congress

Other posts in this series: