The Fountainhead, part 2, chapter 15

As I’ve observed several times before, The Fountainhead is something I’ve never seen: a good book stuck inside a bad book. The story of Peter Keating – his burning ambition to succeed, the compromises he makes in pursuit of that goal, his rise to the top, his discovery that success is hollow, and his ultimate fall – makes for deeply human tragedy. If the book had been about him, it could have been a great work of literature.

But the book isn’t about him. Peter isn’t the main character, and his story ends up being peripheral to the real plot. The longer the book goes on, the more Rand loses interest in him. By the end, he’s shunted offstage in favor of Howard Roark, who’s as static and uninteresting as a marble statue. Peter’s denouement basically happens offscreen, while the political monologues grow in importance until they swallow up the plot like a tumor.

Unfortunately, Rand took the wrong lesson from this, since Atlas Shrugged is nothing but political diatribes and static characters. That’s what makes it so eminently mockable. This week, we’ll look at what makes Peter Keating’s plot work, and I’ll venture a guess as to why Ayn Rand dropped the humanity from her writing to focus on clunky message fiction.

Last time, Peter achieved the most unexpected triumph of his life by marrying Dominique. But just when he should be happiest, he feels strangely empty, to the point where he’s avoiding congratulations:

Keating could see the news spreading through the city in widening circles, by the names and social positions of the people who called. He refused to answer the telephone. It seemed to him that every corner of New York was flooded with celebration and that he alone, hidden in the watertight caisson of his room, was cold and lost and horrified.

It’s pointed out to him that he should really visit his boss and Dominique’s father, Guy Francon, and deliver the happy news in person. So he does:

Keating hurried to the office, glad to escape from his house for a while. He entered the office like a perfect figure of a radiant young lover. He laughed and shook hands in the drafting room, through noisy congratulations, gay shouts of envy and a few smutty references. Then he hastened to Francon’s office.

For an instant he felt oddly guilty when he entered and saw the smile on Francon’s face, a smile like a blessing. He tugged affectionately at Francon’s shoulders and he muttered: “I’m so happy, Guy, I’m so happy…”

“I’ve always expected it,” said Francon quietly, “but now I feel right. Now it’s right that it should be all yours, Peter, all of it, this room, everything, soon.”

Peter is suddenly, inexplicably afraid. He says he doesn’t understand, so Guy Francon spells it out. He’s old and tired, he plans to retire soon, and he wants to make Peter the owner of the firm. He sees him as a worthy heir, especially now that Peter is his son-in-law.

“I want you to feel proud of me, Peter,” said Francon humbly, simply, desperately. “I want to know that I’ve accomplished something. I want to feel that it had some meaning. At the last summing up, I want to be sure that it wasn’t all — for nothing.”

“You’re not sure of that? You’re not sure?” Keating’s eyes were murderous, as if Francon were a sudden danger to him.

“What’s the matter, Peter?” Francon asked gently, almost indifferently.

“God damn you, you have no right — not to be sure! At your age, with your name, with your prestige, with your…”

Again, I have no qualms saying it: This is a great scene! At the moment when Peter has achieved everything he wanted, he begins to realize that it’s all for naught. It’s a sharp dart of irony that flows naturally from the contrast between him and his older, world-wearier boss.

Peter has always been chasing that mirage just over the horizon, always seeking one more triumph that will prove his worthiness beyond all question. It’s terrifying for him that Guy Francon, with his far longer and more prestigious career and greater record of accomplishment, still isn’t sure if his life meant anything. Peter sees himself in Guy’s shoes a few decades down the road, and the knowledge that someone in that position can entertain doubt is an unwelcome clue that he’s reaching for something he can never catch.

Through Peter Keating, Rand identified a real philosophical problem, one that we all have to face in our lives. We humans are small and fragile; our lives are fleeting, our time is limited. How do we find meaning and purpose despite our nature as finite beings? How do we know that we matter, when the world is so vast and so seemingly indifferent? How do we shout our worth loud enough to make the cosmos hear us and acknowledge?

Here’s my guess at why Rand dropped this theme in her later work: because she didn’t have an answer to it either. She was good at raising the question, but struggled to find a philosophically satisfying resolution.

Her only answer is: “Be Howard Roark” – but Roark was born that way. He never experiences a moment of despair. He never questions his purpose in life. He never passes a sleepless night staring at the ceiling, gnawed by doubt. He never feels the chilly whisper of impostor syndrome. He’s immune to all those anxieties that lash at lesser mortals. If you’re not already like him, The Fountainhead suggests it’s too late. (Note that it’s not just a matter of being a heroic individualist. Even other good-guy characters, like Steven Mallory and Henry Cameron, still grapple with uncertainty and fear.)

Peter and Dominique entertain guests all day, a circle of friends and well-wishers coming to congratulate them. Dominique is a perfectly proper, gracious hostess, playing her part flawlessly. And late that night, after the last visitor has left:

They sat at opposite ends of the living room, and Keating tried to postpone the moment of thinking what he had to think now.

“All right, Peter,” said Dominique, rising, “let’s get it over with.”

When he lay in the darkness beside her, his desire satisfied and left hungrier than ever by the unmoving body that had not responded, not even in revulsion, when he felt defeated in the one act of mastery he had hoped to impose upon her, his first whispered words were: “God damn you!”

He heard no movement from her.

So basically, it’s “lie back and think of England”. I’m tempted to say “At least he didn’t rape her” – she clearly consented, even if it was without enthusiasm – but I’m afraid that this book doesn’t treat that as a positive. Unlike Roark, Peter isn’t heroic enough to just know without being asked that Dominique wants to be taken. (Remember, people, the key to a good sex life is communication! Ask your partner what they like to do in bed, you may be surprised.)

But this next bit is another good one:

Then he remembered the discovery which the moments of passion had wiped off his mind.

“Who was he?” he asked.

“Howard Roark,” she answered.

“All right,” he snapped, “you don’t have to tell me if you don’t want to!”

Come on, you have to admit that was funny. Rand had a talent for irony that you can glimpse (rarely) in this novel, but by the time she wrote Atlas, it had all but vanished.

The next day, Ellsworth Toohey comes to visit them for breakfast. He seems pleased, asking Dominique, “So you’ve come back to the fold?” Peter is pulled away for a phone call, and he asks her how she likes married life, teasing her that he knows Peter isn’t the man she truly wanted.

She did not look disgusted; she looked genuinely puzzled.

“What are you talking about, Ellsworth?”

“Oh, come, my dear, we’re past pretending now, aren’t we? You’ve been in love with Roark from that first moment you saw him in Kiki Holcombe’s drawing room — or shall I be honest? — you wanted to sleep with him — but he wouldn’t spit at you — hence all your subsequent behavior.”

“Is that what you thought?” she asked quietly.

“Wasn’t it obvious? The woman scorned. As obvious as the fact that Roark had to be the man you’d want. That you’d want him in the most primitive way. And that he’d never know you existed.”

“I overestimated you, Ellsworth,” she said. She had lost all interest in his presence, even the need of caution. She looked bored. He frowned, puzzled.

This idea – that the otherwise-omniscient Toohey almost understands Dominique, but fails to grasp one key thing – seems like an obvious Chekhov’s gun. In a better novel, it would be the key that the heroes use, somehow, to defeat him. In this novel, Roark doesn’t care about defeating him and never tries to oppose him, so it doesn’t come up.

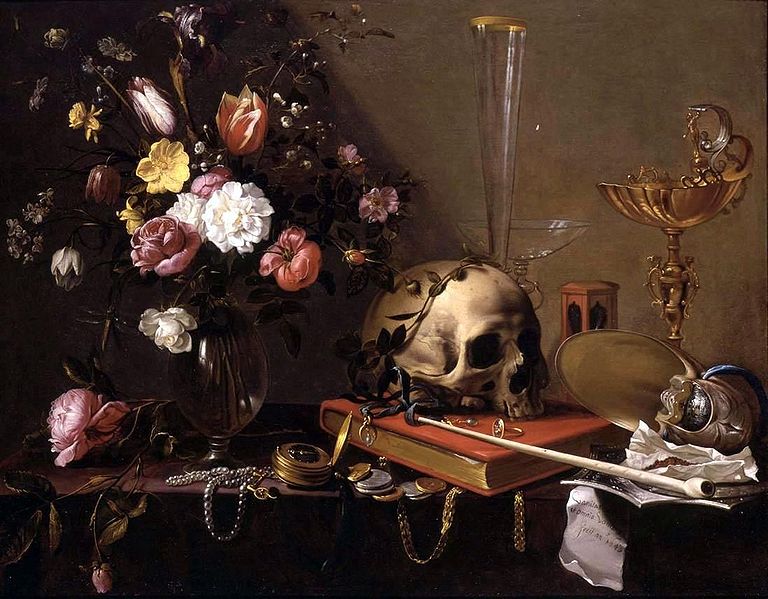

Image: “Vanitas”, an artistic motif contrasting objects of luxury and pleasure with a skull as a reminder of the inevitability of death. Via Wikimedia Commons.

Other posts in this series: