The Fountainhead, part 3, chapter 2

Peter Keating and Dominique Francon have been married for twenty months. For all that time, Dominique has been a perfect, gracious, attentive wife: behaving flawlessly at dinner parties, obeying his every wish, never arguing, never complaining, never nagging. And it’s slowly driving him crazy:

He thought of how convincingly he could describe this scene to friends and make them envy the fullness of his contentment. Why couldn’t he convince himself? He had everything he’d ever wanted. He had wanted superiority — and for the last year he had been the undisputed leader of his profession. He had wanted fame — and he had five thick albums of clippings. He had wanted wealth — and he had enough to insure luxury for the rest of his life. He had everything anyone ever wanted. How many people struggled and suffered to achieve what he had achieved? How many dreamed and bled and died for this, without reaching it?

One night, casting about for a change of pace, he decides he wants to move out of Manhattan:

“I think I’d like to move to the country and build a house of our own. Would you like that?”

“I’d like it very much. Just as you would. You want to design a home for yourself?”

“Hell, no. Bennett will dash one off for me. He does all our country homes. He’s a whiz at it.”

“Will you like commuting?”

“No, I think that will be quite an awful nuisance. But you know, everybody that’s anybody commutes nowadays. I always feel like a damn proletarian when I have to admit that I live in the city.”

Dominique asks, politely, what about country living appeals to him, but he shoots each of her suggestions down. He has no interest in designing a house for himself, he’s not looking forward to commuting, he has no interest in gardening or horseback riding, he doesn’t care about nature, and he’s not even concerned about privacy – in fact, he thinks the home should be near a highway so everyone can see it and feel envious. He’s just doing it because he thinks it’s what wealthy or successful people are supposed to do, not because he genuinely wants to:

“Well, I don’t believe in that desert-island stuff. I think the house should stand in sight of a major highway, so people would point out, you know, the Keating estate. Who the hell is Claude Stengel to have a country home while I live in a rented flat? He started out about the same time I did, and look where he is and where I am, why, he’s lucky if two and a half men ever heard of him, so why should he park himself in Westchester and…”

And he stopped. She sat looking at him, her face serene.

“Oh God damn it!” he cried. “If you don’t want to move to the country, why don’t you just say so?”

“I want very much to do anything you want, Peter. To follow any idea you get all by yourself.”

That’s when he figures out what’s been wrong with her this whole time, why he’s felt so unfulfilled. She’s been so passive, he might as well have married a mannequin:

“Dominique, you’ve never said, not once, what you thought. Not about anything. You’ve never expressed a desire. Not of any kind.”

“What’s wrong about that?”

… “You’re not here. You’ve never been here. If you’d tell me that the curtains in this room are ghastly and if you’d rip them off and put up some you like — something of you would be real, here, in this room. But you never have. You’ve never told the cook what dessert you liked for dinner. You’re not here, Dominique. You’re not alive. Where’s your I?”

“Where’s yours, Peter?” she asked quietly.

He’s stung and angry by the implicit accusation, but he’s come close enough to the mark that she admits what she’s doing:

“My real soul, Peter? It’s real only when it’s independent — you’ve discovered that, haven’t you? It’s real only when it chooses curtains and desserts — you’re right about that — curtains, desserts and religions, Peter, and the shapes of buildings. But you’ve never wanted that. You wanted a mirror. People want nothing but mirrors around them. To reflect them while they’re reflecting too. You know, like the senseless infinity you get from two mirrors facing each other across a narrow passage. Usually in the more vulgar kind of hotels. Reflections of reflections and echoes of echoes. No beginning and no end. No center and no purpose.”

I’m not going to spend too much time analyzing this “second-hander” philosophy of The Fountainhead. Even Ayn Rand seemed to consider it a dead end, considering she dropped it from her later books.

Instead, I want to touch on a more interesting issue that, like others in this book, is brought up but relegated to background material. We talked last week about how Rand anticipated the modern suburb, and the other side of that coin – as we see here – is the commuter lifestyle.

For most of human history, people had no choice but to live near their jobs. The idea of living in one place and traveling to another to work began in the mid-1800s with the rise of railroads, but the suburbs and the automobile drastically accelerated it. In 2013, 86% of workers commuted by car, a whopping 76% driving alone.

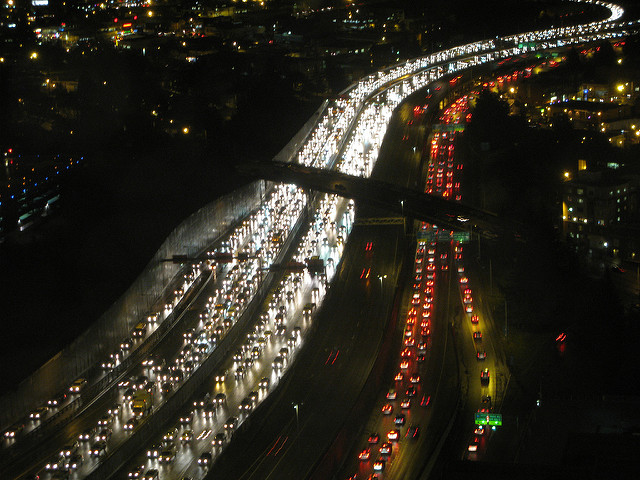

And it’s only getting more pervasive. The average commute is lengthening, and the last few years have seen a boom in “super-commuters“, usually defined as people who travel at least 90 minutes to get to work. As many as 2 million Americans are super-commuters, most clustered around the ultra-expensive cities of New York, San Francisco and Los Angeles, although the phenomenon exists in all urban areas.

Part of the problem is the skyrocketing real-estate prices in prosperous cities, which mean that only the most highly paid employees can afford to live in the communities where they work, while everyone else gets pushed out to the margins. I wrote about this previously in a post on housing shortages and unaffordable rents.

However, another part of the problem is that many people simply fail to factor in the true cost of commuting when choosing where to live. It’s not just the financial costs of gas, tolls and depreciation of your car, or even the health costs of obesity, high blood pressure and back problems associated with sitting in traffic rather than exercising or sleeping. Possibly more than anything else, it’s the long-term emotional toll of aggravation, stress and burnout.

Study after study finds that commuting is one of the worst things for overall happiness and life satisfaction, and owning a bigger house with a lawn doesn’t make up for it. One study found that an extra 20 minutes of commuting per day has the same negative consequences for happiness as a 19% pay cut. Another concluded that shortening your commute by an hour would give you the same happiness boost as making an extra $40,000 a year. Couples with long commutes are more likely to divorce.

We’d be better off if more people knew they’d be happier choosing the small high-rise apartment close to work, rather than the big spacious house out in the suburbs. However, this problem ultimately demands a solution at a societal level, not an individual level. To ease the pain of commuting, what we need is smart density – essentially, designing neighborhoods for people and not for cars. The worst commuting problems come from sprawl: the spread-out, low-density suburbs where people have no choice but to drive if they want to get anywhere.

And it’s not just bad for the happiness of the people caught in those daily mega-traffic jams. Urban sprawl is bad for the environment: the wildlife habitats that need to be bulldozed, the extra greenhouse gases and other air pollution emitted by that sweltering fume of cars, all the (most likely fossil-fuel-derived) energy needed to heat and cool those spacious detached houses.

Since it’s ostensibly a book about architecture, The Fountainhead could have talked at least a little about how neighborhood design affects our lives, but it’s uninterested in the subject. It treats architecture as a purely atomistic profession. Howard Roark’s only concern is building his individual heroic buildings, without regard for who will live in them or what effect they’ll have on the surrounding community. Ironically, that’s the same attitude that gave rise to pestilential sprawl in the first place.

Image credit: Oran Viriyincy, released under CC BY-SA 2.0 license

Other posts in this series: