The Fountainhead, part 3, chapter 3

By offering to sleep with him, Dominique has convinced Gail Wynand to give the commission for his Stoneridge real-estate development to her husband, Peter Keating. When Ellsworth Toohey gave Wynand the statue of Dominique that set all this in motion, he claimed not to remember who had made it. Of course, Dominique tells him that the sculptor was Steven Mallory:

Toohey had expected Wynand to call for him after the interview with Dominique. Wynand had not called. But a few days later, meeting Toohey by chance in the city room, Wynand asked aloud:

“Mr. Toohey, have so many people tried to kill you that you can’t remember their names?”

Toohey smiled and said: “I’m sure quite so many would like to.”

“You flatter your fellow men,” said Wynand, walking away.

We talked in Atlas Shrugged about the contradiction between what Rand shows and what she tells. She claims to be against “initiation of force” – in fact, that’s a cornerstone of her libertarian philosophy – and yet she cheers her heroes when they commit acts of violence and terrorism to achieve their goals. Steven Mallory in this book is an example. Although he failed in his attempt to murder Ellsworth Toohey, we’re meant to understand that it was a noble effort, and none of the other protagonists condemn him for it.

This section is another case in point. Gail Wynand thinks it’s a compliment – and an undeserved compliment, at that – to say that a lot of people would like to kill Ellsworth Toohey if only they could. The message is not only that murdering the right people is a praiseworthy deed, but that the majority of humanity falls short of that standard. Most people aren’t heroic enough to want to go out and commit murder. Ayn Rand is actually condemning humanity by saying that most of us aren’t willing to shoot a stranger in cold blood!

In the next scene, Peter Keating meets Gail Wynand at an expensive restaurant. Peter is enjoying the envious stares of the other diners who recognize the two of them sitting together, and he’s even more pleased and astonished when Wynand tells him that the Stoneridge project is his. He doesn’t know about the deal that Dominique and Wynand struck, so he thinks he’s been chosen on merit alone:

“I had not hoped that my works were of sufficient importance to attract your attention, Mr. Wynand.”

“But I know them quite well. The Cosmo-Slotnick Building, which is pure Michelangelo.” Keating’s face spread in incredulous pleasure; he knew that Wynand was a great authority on art and would not make such comparisons lightly. “The Prudential Bank Building, which is genuine Palladio. The Slottern Department Store, which is snitched Christopher Wren.” Keating’s face had changed. “Look what an illustrious company I get for the price of one. Isn’t it quite a bargain?”

Keating believes – or really, wants to convince himself – that Gail Wynand is just teasing him, making a light-hearted joke at his expense. But that polite pretense is quickly shattered:

Wynand half turned in his chair and looked at Dominique, as if he were inspecting an inanimate object.

“Your wife has a lovely body, Mr. Keating. Her shoulders are too thin, but admirably in scale with the rest of her. Her legs are too long, but that gives her the elegance of line you’ll find in a good yacht. Her breasts are beautiful, don’t you think?”

… “I appreciate compliments, Mr. Wynand, but I’m not conceited enough to think that we must talk about my wife.”

“Why not, Mr. Keating? It is considered good form to talk of the things one has — or will have — in common.”

Peter is stunned speechless when he realizes what Wynand is driving at. When he stammers that “things like this aren’t being done,” Wynand says, “That’s not what you mean at all, Mr. Keating. You mean, they’re being done all the time, but not talked about.”

Wynand says that Keating only has to say the word, and he’ll call off the deal and give Stoneridge to some other architect. Feeling nauseous, barely able to speak, Keating nevertheless declines. He feels as if he’s being murdered himself: “He thought: blood on paving stones — all right, but not blood on a drawing-room rug…”

Wynand makes an smug aside to Dominique, reminding her of her quest to degrade herself: “I said it was a quest at which you would never succeed. Look at your husband. He’s an expert — without effort. That is the way to go about it.”

Keating noticed that his palms were wet and that he was trying to support his weight by holding on to the napkin on his lap. Wynand and Dominique were eating, slowly and graciously, as if they were at another table. Keating thought that they were not human bodies, either one of them; something had vanished; the light of the crystal fixtures in the room was the radiance of X-rays that ate through, not the bones, but deeper; they were souls, he thought, sitting at a dinner table, souls held with evening clothes, lacking the intermediate shape of flesh, terrifying in naked revelation — terrifying, because he expected to see torturers, but saw a great innocence. He wondered what they saw, what his own clothes contained if his physical shape had gone.

This is a classic example of a character having access to information that only the author should have. Ayn Rand intends this scene to show how worthless Peter Keating is, because he meekly agrees to swap his wife in exchange for a commission that he covets and that will make him even more famous. He immediately grasps that this is the bargain he’s being offered, and his inability to say no to Wynand proves his lack of spine.

But wait: Peter has no reason to think this is anything but a veiled threat. As we’ve already established, Gail Wynand is a dangerous man to cross. He has a reputation for making people offers they can’t refuse, and sadistically destroying their lives if they won’t work for him on the terms he sets.

Peter has no reason to believe this isn’t another of those offers, or that Wynand won’t ruin both his life and Dominique’s if he says no. In fact, the clothes she chose to wear to dinner – a plain white silk dress that made her look like “a sacrificial object publicly offered” – plus her passivity and silence in the face of Wynand’s offensive language, plus the fact that she didn’t discuss this with him in advance, ought to give him an obvious alternative explanation. Why wouldn’t he think that she isn’t also being blackmailed in the same way?

But instead of seeing Wynand as a malevolent, rapist villain, which he should based on the evidence available to him, Peter somehow perceives his and Dominique’s souls and what he sees is a “great innocence”. He just knows, in some mysterious way, that they’re not doing anything wrong.

In fact, what they’re doing is correct in the author’s eyes, because they’re both True Objectivists under the skin and a True Objectivist is philosophically required to have sex with whoever best exemplifies their capitalist values, regardless of any prior commitments they’ve made. Peter Keating is a nonentity, so his feelings on the matter are irrelevant. (This is a bizarre literary foreshadowing of Ayn Rand’s real life, since she later insisted it was mandatory for her chief acolyte Nathaniel Branden to have sex with her, notwithstanding the fact that they were both married to other people.)

Also, this begs the question: how would this scene have played out if it were Howard Roark sitting at that table? Would he have willingly sold Dominique for the chance to get his hands on a prestigious architectural commission?

From what we know of Roark, I’d have to conclude that the answer is yes. It’s clear that whatever he feels for Dominique, he loves architecture more. He would hardly be a Randian protagonist if it were otherwise. In a later chapter, she offers to marry him if he gives up architecture, and he laughs at her: “I wish I could tell you that it was a temptation, at least for a moment. But it wasn’t.”

Plus, Rand has endorsed similar attitudes before. Remember, in Atlas Shrugged, Hank Rearden told Dagny Taggart he should have demanded she have sex with him as the price of their companies doing business, and we’re meant to take this as flirtatious banter and not the revelation of an abusive sexual predator. Clearly, Ayn Rand isn’t averse to that sort of trade.

So, assuming Roark would have done the same thing, why would that be okay for him and not for Peter? Because he’d have accepted the tradeoff gladly rather than reluctantly? Are we meant to think that Peter’s devotion to his wife is a character flaw, and that the true weakness he displays in this scene isn’t his inability to resist Wynand’s offer, but the fact that he agonizes over it at all?

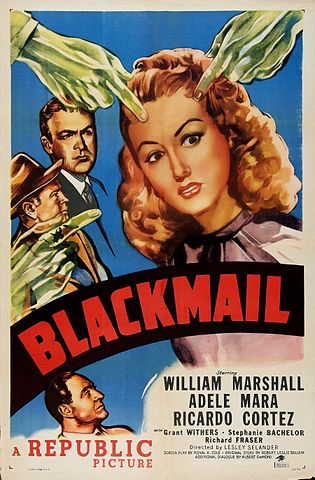

Image credit: Wikimedia Commons

Other posts in this series: