The Fountainhead, part 4, chapter 1

After signing the contract to build Monadnock Valley, Howard Roark goes to work. His old employees gladly come back to join him, and they endure punishing, Washington-at-Valley-Forge-like conditions to finish the job in as short a time as possible:

For the last year he lived at the construction site, in a shanty hastily thrown together on a bare hillside, a wooden enclosure with a bed, a stove and a large table. His old draftsmen came to work for him again, some abandoning better jobs in the city, to live in shacks and tents, to work in naked plank barracks that served as architect’s office.

…They did not think of the snow, the frozen clots of earth, wind whistling through the cracks of planking, thin blankets over army cots, stiff fingers stretched over coal stoves in the morning, before a pencil could be held steadily.

We’re told that Roark is such a genius, and this project is such a great accomplishment, that his workers are willing to disregard creature comforts just for the chance to be part of it.

However, this isn’t a special case. It illustrates Rand’s view of how ordinary workers should always behave: they should be so passionately devoted to the job, so cultishly eager to obey their boss’ every command, that they willingly tolerate brutal and dangerous conditions. (How many of those designers lost fingertips to frostbite?)

She believes that being allowed to labor on behalf of an Objectivist Superman is its own reward. As I’ve observed before, this is eerily similar to the utopian ideals of communism, except with an omniscient individual boss substituted for the omniscient state.

They were an army and it was a crusade. But none of them thought of it in these words, except Steven Mallory. Steven Mallory did the fountains and all the sculpture work of Monadnock Valley. But he came to live at the site long before he was needed. Battle, thought Steven Mallory, is a vicious concept. There is no glory in war, and no beauty in crusades of men. But this was a battle, this was an army and a war — and the highest experience in the life of every man who took part in it.

This is one of the few good parts of Objectivism that doesn’t get emphasized enough. Since Ayn Rand said that “initiation of force” was always wrong, she should be against war and violence of all kinds (although we’ve seen that she takes a, shall we say, flexible definition of what counts as self-defense).

However, Steven Mallory’s firm avowal that there’s no glory in war seems incompatible with John Galt’s declaration in Atlas Shrugged that he and his fellow capitalists will return to violently conquer what’s left of the world after destroying civilization. Maybe that’s justified because, in Galt and therefore Rand’s eyes, it’s not war, it’s pest control.

Ayn Rand would have made a good Dalek.

Strangely, after Monadnock Valley is complete, the investors who hired Roark to build it seem to vanish from the face of the earth. They run only a few obscure ads, not the publicity blitz that everyone is expecting. But in spite of their silence, word of mouth spreads, and the resort is soon booked solid:

But within a month of its opening every house in Monadnock Valley was rented. The people who came were a strange mixture: society men and women who could have afforded more fashionable resorts, young writers and unknown artists, engineers and newspapermen and factory workers. Suddenly, spontaneously, people were talking about Monadnock Valley. There was a need for that kind of a resort, a need no one had tried to satisfy.

Everything seems to be coming up roses for our hero. Then, one morning, Steven Mallory bursts into Roark’s office and throws a newspaper down on the table. The truth has come out: Monadnock Valley was an elaborate fraud, and the people who hired Roark have just been arrested.

Mallory spoke with a forced, vicious, self-torturing precision. “They thought it was worthless — from the first. They got the land practically for nothing — they thought it was no place for a resort at all — out of the way, with no bus lines or movie theaters around — they thought the time wasn’t right and the public wouldn’t go for it. They made a lot of noise and sold snares to a lot of wealthy suckers — it was just a huge fraud. They sold two hundred percent of the place. They got twice what it cost them to build it. They were certain it would fail. They wanted it to fail. They expected no profits to distribute. They had a nice scheme ready for how to get out of it when the place went bankrupt. They were prepared for anything — except for seeing it turn into the kind of success it is. And they couldn’t go on — because now they’d have to pay their backers twice the amount the place earned each year. And it’s earning plenty. And they thought they had arranged for certain failure. Howard, don’t you understand? They chose you as the worst architect they could find!”

Roark threw his head back and laughed.

“God damn you, Howard! It’s not funny!”

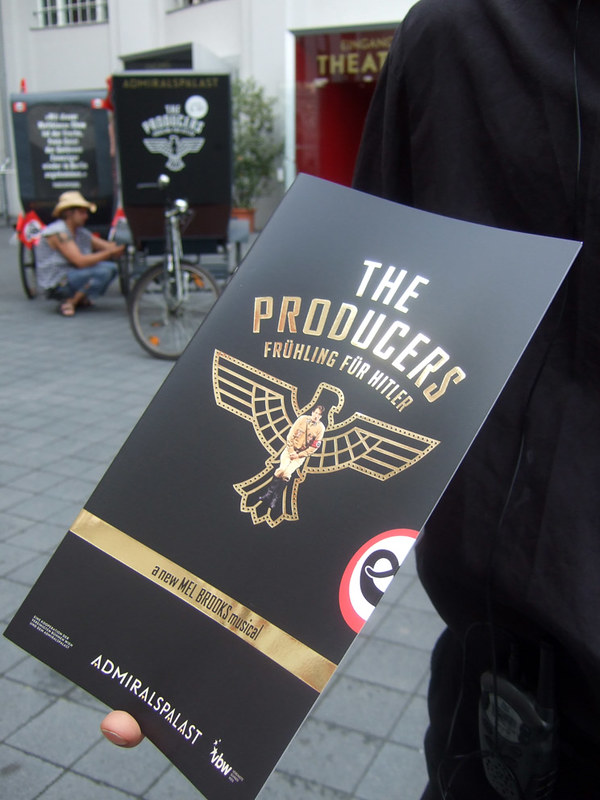

Yes, if this sounds familiar, it should. It’s the same story as the plot of The Producers.

Mallory is furious that the Monadnock Valley scammers chose Howard Roark because they expected him to build something that everyone would hate. He says that it’s objectively worse than “a whole field of butchered bodies”:

“What do the damn fools think of as horror? Wars, murders, fires, earthquakes? To hell with that! This is horror — that story in the paper. That’s what men should dread and fight and scream about and call the worst shame on their record.”

Just like Steven Mallory having to make tacky tourist sculptures is worse than a field full of people mowed down by tanks, the worst evil – the very worst thing in the world – is when Rand’s Heroic Creators don’t get to do exactly what they want at all times.

If the cruel world denies them their creative freedom, or even if it does give them creative freedom but for the wrong reasons, we’re meant to see this as the ultimate evil. Because they matter more than everyone else, the slightest infringement of their desires is objectively worse than the most horrific suffering of any number of lesser mortals. Mallory says it’s worse than murder or war. (We also saw this in Atlas Shrugged, where a millionaire having to give up a patent is depicted as worse than being robbed, beaten or killed.)

This casts a dubious light on Rand’s avowal of pacifism. She might say that she’s against war, violence and other crimes, but in practice, the desire of the super-rich to be free of taxes, regulations and moral sanctions will always be her top priority.

However, for all of Mallory’s horror, Roark’s amusement seems like the more natural, human reaction. After all, he hasn’t lost anything on this deal. He got paid, and he got to build what he wanted, even if the people who hired him did so for bad motives.

Besides, the buzz about Monadnock Valley proves to be good for his battered reputation. The simple, unbeatable argument that “Roark had built a place which made money for owners who didn’t want to make money” turns the heads of other clients who wouldn’t have given him the time of day before this:

Then Austen Heller wrote an article about Howard Roark and Monadnock Valley. He spoke of all the buildings Roark had designed, and he put into words the things Roark had said in structure. Only they were not Austen Heller’s usual quiet words — they were a ferocious cry of admiration and of anger. “And may we be damned if greatness must reach us through fraud!”

… “Howard,” Mallory said one day, some months later, “you’re famous.”

“Yes,” said Roark, “I suppose so.”

“Three-quarters of them don’t know what it’s all about, but they’ve heard the other one-quarter fighting over your name and so now they feel they must pronounce it with respect. Of the fighting quarter, four-tenths are those who hate you, three-tenths are those who feel they must express an opinion in any controversy, two-tenths are those who play safe and herald any ‘discovery,’ and one-tenth are those who understand. But they’ve all found out suddenly that there is a Howard Roark and that he’s an architect.”

In other words, there’s no such thing as bad publicity. And Roark’s friend Kent Lansing (the thin, angular guy who looks like a boxer) agrees:

Kent Lansing said, one evening: “Heller did a grand job. Do you remember, Howard, what I told you once about the psychology of a pretzel? Don’t despise the middleman. He’s necessary. Someone had to tell them. It takes two to make a very great career: the man who is great, and the man — almost rarer — who is great enough to see greatness and say so.”

This is the weirdest example I’ve ever seen of a novel trying to impart a lesson seemingly against the will of its own author.

We’ve seen that Henry Cameron was more dependent than he knew on his faithful business manager who could find clients and persuade them to put up with Cameron’s insults. We’ve seen the gross failure of Howard Roark’s “sit in motionless silence and wait for clients to come to me” marketing strategy.

And now we’ve seen another character spell out the lesson: even great men, in order to succeed, have to have someone who can sell their greatness to the rest of the world. It’s not enough to sit back and wait for people to discover you. But it’s a lesson that the ostensible hero never learns, because Roark never does do any advertising on his own behalf. In fact, by the time Rand wrote Atlas Shrugged, she had entire multinational companies which seemed to have no marketing or PR departments.

Image credit: Admiralspalast Berlin, released under CC BY-ND 2.0 license

Other posts in this series: