The Fountainhead, part 4, chapter 2

Howard Roark returns to his office after a day at a job site, and his secretary excitedly tells him that she has big news:

“I made an appointment for you for three o’clock tomorrow afternoon. At his office.”

“Whose office?”

“He telephoned half an hour ago. Mr. Gail Wynand.”

Gail Wynand is, of course, the one person in the world that Howard Roark has the most reason to despise (the way Rand describes it is “the man who had made him feel his nearest approach to hatred,” because her protagonist wouldn’t be good enough for her if he had emotions like other human beings).

Wynand’s sleazy, lowbrow newspaper employs Ellsworth Toohey, Roark’s nemesis. The Banner‘s attacks on him were directly responsible for the destruction of the Stoddard Temple, and indirectly responsible for causing people to hate modern architecture in general. Worst of all, Gail Wynand married Dominique Francon, the woman Roark wants.

Nevertheless, Roark shows up at the appointed time. For his part, from his office atop the Banner Building, Wynand is looking forward to the meeting with no greater emotion than the casual disdain he feels for his fellow human beings.

But once again, Objectivist Telepathy is in play. No conversation between them is necessary. They don’t have to meet a challenge they can overcome together so they can find out that they have a common view of the world. Like Dagny meeting the inhabitants of Galt’s Gulch, all it takes is a single, meaningful glance into each other’s eyes, and they immediately understand each other:

Wynand was not certain that he missed a moment, that he did not rise at once as courtesy demanded, but remained seated, looking at the man who entered… Roark was not certain that he stopped when he entered the office, that he did not walk forward, but stood looking at the man behind the desk… But there had been a moment when both forgot the terms of immediate reality, when Wynand forgot his purpose in summoning this man, when Roark forgot that this man was Dominique’s husband… only the total awareness, for each, of the man before him, only two thoughts meeting in the middle of the room — “This is Gail Wynand” — “This is Howard Roark.”

Normally I’d say that this is just lazy writing, that Ayn Rand wanted to get on with her Roark-Wynand best-bros teamup without that tedious character-development stuff, and that Objectivist Telepathy is a handy literary shortcut to achieve this.

But no – there are people who think this is the way the world actually works, that you can discern someone’s inmost character from the squareness of their jaw or the firmness of their handshake. For example, George W. Bush once claimed that he trusted Vladimir Putin because “I looked in his eyes and saw his soul” (you can judge for yourself how accurate this assessment proved to be). The Randian belief that a person’s outward appearance is intrinsically linked to their trustworthiness is a reliable driver of affinity fraud both religious and secular.

Then Wynand rose, his hand motioned in simple invitation to the chair beside his desk, Roark approached and sat down, and they did not notice that they had not greeted each other.

Wynand smiled, and said what he had never intended to say. He said very simply:

“I don’t think you’ll want to work for me.”

“I want to work for you,” said Roark, who had come here prepared to refuse.

Wynand says that he’s never built anything for himself before, only for his business empire, but that’s about to change:

“Can you tell me why I’ve never built a structure of my own, with the means of erecting a city if I wished? I don’t know. I think you’d know.” He forgot that he did not allow men he hired the presumption of personal speculation upon him.

“Because you’ve been unhappy,” said Roark.

He said it simply, without insolence; as if nothing but total honesty were possible to him here. This was not the beginning of an interview, but the middle; it was like a continuation of something begun long ago.

Roark’s explanation is that the houses we build, like the clothes we wear or the music we listen to or the cigarettes we smoke, is an attempt to make real the inner lives we all lead inside our heads: “to bring that life into physical reality, to state it in gesture and form”. If a man has the means to build what he wants, but chooses not to do so, “it’s because his life has not been what he wanted.”

To paraphrase what Freud probably never said: aren’t there times when a house is just a house?

After all, there might be a small handful of multimillionaires who can choose their site, their materials and their style purely to send a message, but that’s not the norm. The vast majority of people choose the house they do because of utilitarian reasons – a good location, low taxes, cheap land, good schools, convenient to work, brand-new appliances and granite countertops – not because they want to make some philosophical statement about how they see the world.

This is a bizarre theme that recurs in Ayn Rand’s works: she believed, in the face of the evidence, that a person’s entire “sense of life” could be discerned from even their smallest, seemingly trivial, choices. That read, as I’ve previously observed, to some comical episodes as her acolytes scrambled to mimic whatever preferences she expressed.

Wynand says that Roark’s diagnosis is almost right. He was unhappy, but not anymore. He’s purchased five hundred acres of land in Connecticut, and he wants Roark to build a house for him:

“Did Mrs. Wynand choose me for the job?”

“No. Mrs. Wynand knows nothing about this. It was I who wanted to move out of the city, and she agreed. I did ask her to select the architect — my wife is the former Dominique Francon; she was once a writer on architecture. But she preferred to leave the choice to me… I went around the country, looking at homes, hotels, all sorts of buildings. Every time I saw one I liked and asked who had designed it, the answer was always the same: Howard Roark. So I called you.”

Since this chapter concerns Gail Wynand and his lavish country estate, it’s a good place to return to a topic that deserves more attention.

In this series, I’ve previously written about restrictive covenants and how they established a pattern of segregation that persists even today. But I have more to say about the continuing fallout of that bigoted policy choice. It’s not just homeownership rates or the racial composition of the suburbs that are affected, it’s people’s entire economic future.

Witness the points made in this editorial, “Blacks Still Face a Red Line on Housing“:

For generations of white American families, homeownership has been a fundamental means of accumulating wealth. Their homes have grown in value over time, providing security in retirement and serving as an asset against which they can borrow for education or other purposes.

But African-Americans were essentially shut out of early federal programs that promoted homeownership and financial well-being — including the all-important New Deal mortgage insurance system that generated the mid-20th-century homeownership boom. This missed opportunity to amass wealth that white Americans took for granted is evident to this day…

An analysis by the nonprofit Urban Institute shows that between 2001 and 2016 the homeownership rate for African-Americans declined about five percentage points, to 41 percent, as opposed to just one percentage point for whites, whose rate fell to just over 71 percent… The Urban Institute’s analysis of the black-white homeownership gap in 100 cities across the country shows that none have actually closed the ownership gap.

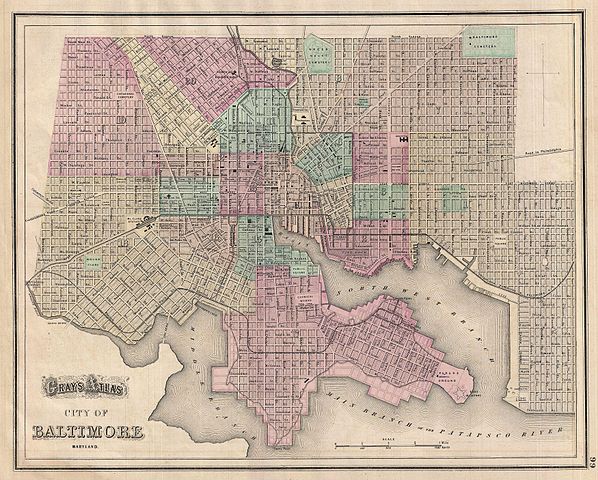

This was the origin of the term “redlining“: literal red lines on maps, drawn around majority-minority neighborhoods which were deemed ineligible for loan refinancing and federally backed mortgage insurance.

If you’d rather get your history in video form, here’s a clip from the show Adam Ruins Everything which points out that “the fact that so many suburbs are mostly white is no accident”. It’s the planned and intended result of decades of racist public policy:

New Deal-era home loans were preferentially given to white families, allowing them to build equity, and this initial advantage compounded over time. White homeowners could benefit from price appreciation in desirable neighborhoods; could build wealth and social capital when businesses moved to those desirable neighborhoods and created jobs there; could see their children benefit from living in wealthier communities that could pay for better public schools; and could pass all these advantages down when children inherited their parents’ homes and could rent them or sell them for extra income.

Meanwhile, minority families that were shut out of homeownership accrued none of these benefits. Instead, they suffered the flip side of that feedback loop: segregated neighborhoods couldn’t pay for good education or attract profitable businesses, trapping most of their residents in ghettos, leaving them at the mercy of rent-seeking landlords, and creating poverty that perpetuates itself across generations.

And that’s not to mention the blatant discrimination that still exists, like real-estate agents steering minority buyers away from desirable homes, or banks charging them higher interest rates than white buyers with the same credit score. All these effects have conspired to create a large and persistent racial wealth gap in America, one that may never close on its own if we don’t actively work to counteract it.

Image: Baltimore street map, 1874. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Other posts in this series: