The Fountainhead, part 4, chapter 7

Peter Keating is going down in the world. His architectural firm has shrunk and laid off employees, and is still losing money. He “had lost a large part of his personal fortune in careless stock speculation” but has enough to live comfortably for the rest of his life. What really worries him is “the question mark looming beyond”.

Peter’s last major work, the March of the Centuries exhibition (the one Howard Roark refused to participate in because he couldn’t have it all to himself) was a flop, despite the fact that he and the other architects genuinely tried to collaborate:

Keating thought, with wistful bitterness, of how conscientiously they had worked, he and the seven other architects, designing those buildings. It was true that he had pushed himself forward and hogged the publicity, but he certainly had not done that as far as designing was concerned. They had worked in harmony, through conference after conference, each giving in to the others, in true collective spirit, none trying to impose his personal prejudices or selfish ideas.

As always, “cooperation” is a snarl word in Ayn Rand’s lexicon. She believed that people working together as a team inevitably makes the end product worse than any of those people would have achieved as individuals.

But this belief is contradicted by empirical evidence, specifically the “wisdom of the crowd” phenomenon: Under the right circumstances, a large group of people can have better judgment than any one individual in that group, because random errors will tend to average out. It’s ironic that she overlooked this phenomenon, because – as this article points out – it’s the major theory for what makes markets work!

Let’s get back to Peter. He’s suffered one other blow, and it’s the cruelest of all: Ellsworth Toohey, who once praised his work and secured him many prestigious commissions, has stopped returning his calls. Toohey’s columns now sing the praises of malicious, talentless hacks like Gus Webb, who are far worse architects than Peter ever was:

For once, Keating could not follow people; it was too clear, even to him, that public favor had ceased being a recognition of merit, that it had become almost a brand of shame.

Was there ever a time when public favor was a recognition of merit, in Rand’s world? It doesn’t seem so. After all, Gail Wynand spent years building up a popular and powerful media empire by pandering shamelessly to the lowest common denominator. Similarly, in Atlas Shrugged, the heroic individualist businessmen are never loved by the public. At best, they’re grudgingly tolerated, and more often they’re hated for their unapologetic devotion to profit.

Peter has no idea what his next move should be. But his business partner, Neil Dumont, does:

It was Neil Dumont who forced him to think of Toohey again. Neil spoke petulantly about the state of the world, about crying over spilt milk, change as a law of existence, adaptability, and the importance of getting in on the ground floor. Keating gathered, from a long, confused speech, that business, as they had known it, was finished, that government would take over whether they liked it or not, that the building trade was dying and the government would soon be the sole builder and they might as well get in now, if they wanted to get in at all. “Look at Gordon Prescott,” said Neil Dumont, “and what a sweet little monopoly he’s got himself in housing projects and post offices. Look at Gus Webb muscling in on the racket.”

Dumont’s speech points Peter toward the holy grail, which he’s been trying not to think about. It’s a public housing project called Cortlandt Homes:

Cortlandt Homes was a government housing project to be built in Astoria, on the shore of the East River. It was planned as a gigantic experiment in low-rent housing, to serve as model for the whole country; for the whole world. Keating had heard architects talking about it for over a year. The appropriation had been approved and the site chosen; but not the architect. Keating would not admit to himself how desperately he wanted to get Cortlandt and how little chance he had of getting it.

Reluctantly, Peter makes an appointment with Toohey – who, for once, agrees to see him – and goes there to beg for the commission. Toohey isn’t officially in charge of the selection, but Peter knows that Toohey has friends in high places (“Anywhere I look, any big name I hear — it’s one of your boys”) and is convinced that a good word from him will tip the balance.

Toohey gloats a while (“I believe we’re all equal and interchangeable. A position you hold today can be held by anybody and everybody tomorrow. Egalitarian rotation. Haven’t I always preached that to you?”), but eventually admits that there’s a small problem:

“Look, I’ll tell you the truth. We’re stuck on that damn Cortlandt. There’s a nasty little sticker involved. I’ve tried to get it for Gordon Prescott and Gus Webb — I thought it was more in their line, I didn’t think you’d be so interested. But neither of them could make the grade. Do you know the big problem in housing? Economy, Peter.

…The boys in Washington don’t want another one of those — you heard about it, a little government development where the homes cost ten thousand dollars apiece, while a private builder could have put them up for two thousand. Cortlandt is to be a model project. An example for the whole world. It must be the most brilliant, the most efficient exhibit of planning ingenuity and structural economy ever achieved anywhere. That’s what the big boys demand. Gordon and Gus couldn’t do it. They tried and were turned down.”

There’s a contradiction here which the text tries to skate over. Rand would have us believe that government projects are always wasteful and inefficient compared to the private sector. But at the same time, because it’s a government project, Cortlandt Homes genuinely has to be cheap and economical – more so than anything that’s currently on the market. This is so strict a requirement that even Toohey, with his vast web of political connections and influence, can’t get around it.

Even if it were true that government housing is more expensive than private-developer-built housing, you have to consider the externalities of the situation. Private housing only helps people who have money to pay mortgages and rent. But people need housing whether they have money to spend or not. What costs does it impose on society to let them remain homeless?

Many chronically homeless people have untreated substance-abuse or mental-health problems. Left to themselves, they bounce back and forth between emergency rooms and jails – which are two of the most expensive ways to “house” people, consuming police and medical resources. This suggests that it might actually be cheaper just to pay for affordable housing, if it helps them get their lives on track. And that’s just what a study from Charlotte, North Carolina found, where local nonprofits partnered with the municipal government to build subsidized housing for the homeless:

According to the UNCC study, that $14,000 [spent to house one person for a year] pales in comparison to the costs a chronically homeless person racks up every year to society — a stunning $39,458 in combined medical, judicial and other costs.

In a similar initiative out of Chicago, the University of Illinois Hospital paid for housing for homeless people who were heavy users of the emergency room. Some of them were faking illness just to get a warm bed or a meal for the night, while others were suffering from chronic health problems that were exacerbated by street living. Either way, paying to house them helped stabilize them and proved to be a huge cost saver:

The hospital pays $1,000 a month for patient housing. One day in the hospital can run about $3,000, a cost generally shared by the hospital, the patient, public assistance programs, and insurance companies.

What’s more, paying to house the homeless doesn’t just benefit the homeless, it protects everyone. Homeless people who live in crowded, dirty, unsanitary conditions – like Los Angeles’ Skid Row, which has been described as “a refugee camp for Americans” – are vulnerable to outbreaks of disease like typhus that can spread to the rest of society.

The idea of government committing to build housing for the poor, and sometimes even the middle class, is hardly radical or revolutionary. It goes by the name “social housing” – housing developments built and managed by local governments and paid for by municipal bonds, the same way that cities build other public amenities like libraries. This is a common arrangement around the world, and not just in Europe. For instance, nearly half of Hong Kong lives in public housing, and in Singapore, it’s 80% of people.

But in the U.S., public housing projects have an unsavory reputation. They’re widely viewed as breeding grounds for poverty, drugs, gang crime and dysfunction, and not just by conservative politicians. Why has such a straightforward, cost-effective solution that’s so widely used around the world turned out so badly here? Next week, we’ll explore that question.

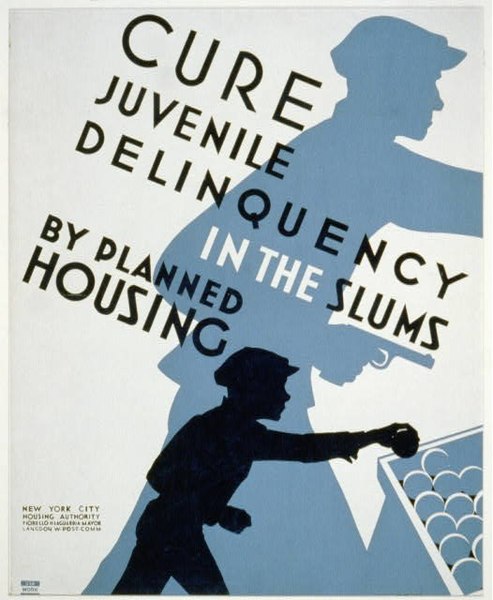

Image: “Cure juvenile delinquency in the slums by planned housing”, a Works Project Administration poster from 1936. Via Wikimedia Commons.

Other posts in this series: