The Fountainhead, part 4, chapter 11

Roark is on Gail Wynand’s yacht, the two of them enjoying a cruise in the tropical seas. In between their romantic-yet-heterosexual interludes, they sunbathe on the deck while discussing the philosophical underpinnings of morality.

As I noted last time, a successful capitalist is by definition a second-hander in Rand’s worldview. This is an implication Rand strains to avoid, even though her own book demonstrates it. Roark is bad at business, bad at finding clients, bad at persuading clients to see things his way, bad at networking, bad at sales, bad at getting along with his colleagues. He’s only rescued from obscurity by a stroke of luck: he happens to get noticed by an uber-wealthy titan of industry who falls in love with his work. This is about as plausible as the supermarket romances where an average girl next door just happens to catch the eye of a lonely yet passionate billionaire.

And like other pairs of star-crossed lovers, while they’re together, Roark and Wynand muse on how they’re the only ones in the world who understand true happiness:

“Look at everyone around us. You’ve wondered why they suffer, why they seek happiness and never find it. If any man stopped and asked himself whether he’s ever held a truly personal desire, he’d find the answer. He’d see that all his wishes, his efforts, his dreams, his ambitions are motivated by other men. He’s not really struggling even for material wealth, but for the second-hander’s delusion — prestige. A stamp of approval, not his own. He can find no joy in the struggle and no joy when he has succeeded. He can’t say about a single thing: ‘This is what I wanted because I wanted it, not because it made my neighbors gape at me.’ Then he wonders why he’s unhappy.”

I grant that Rand wasn’t entirely wrong in her description of the second-hander mentality. There are people who think like this, who crave fame above all else and will try to secure it by fair means or foul. (For some laughs, read “The Empty Mason Jar of the Influencer Economy“, about the inept celebrity-wannabe Caroline Calloway.)

But where Rand goes off the rails is her insistence that this mentality causes every bad thing in the world:

“And isn’t that the root of every despicable action? Not selfishness, but precisely the absence of a self. Look at them. The man who cheats and lies, but preserves a respectable front. He knows himself to be dishonest, but others think he’s honest and he derives his self-respect from that, second-hand. The man who takes credit for an achievement which is not his own. He knows himself to be mediocre, but he’s great in the eyes of others. The frustrated wretch who professes love for the inferior and clings to those less endowed, in order to establish his own superiority by comparison.”

Again, I can agree that there are people who fit this template. We just heard about an unsurpassable example, the college admissions scandal busted by the FBI, in which a ring of wealthy financiers, celebrities and other elites paid bribes, cheated tests and forged applications to guarantee their children’s admission to high-powered universities. That is the second-hander mentality as Rand described it: people who want the prestige of an achievement they didn’t earn.

However, there’s an obvious counterexample to Rand’s thesis: people who commit atrocities because they believe they’re the only ones with a genuine self, and therefore the only ones with rights. In their eyes, everyone else is a non-entity that can be brushed aside, starved, enslaved or slaughtered without qualm. That’s a motivation for evil that doesn’t come from the second-hander mentality, but from its opposite. Psychopaths, racial and religious supremacists, colonizers and conquistadors, caste-system apologists and blood purists, let-them-eat-cake libertarians, and others all fit this description.

Rand anticipates this point and tries to address it, but not very convincingly:

“I think your second-handers understand this, try as they might not to admit it to themselves. Notice how they’ll accept anything except a man who stands alone. They recognize him at once. By instinct. There’s a special, insidious kind of hatred for him. They forgive criminals. They admire dictators. Crime and violence are a tie. A form of mutual dependence. They need ties. They’ve got to force their miserable little personalities on every single person they meet. The independent man kills them — because they don’t exist within him and that’s the only form of existence they know.”

Uh, what? I’m pretty sure the average mugger is unconcerned with what his victims think of him.

Rand tries to force crime and violence into her philosophical framework, but the effort fails. Street criminals and gangsters don’t commit muggings, extortion or burglaries because they want to “force their personalities” on other people, they do it because they don’t recognize the right of others to possess something they want for themselves. Similarly, domestic abusers, rapists, murderers and other sociopaths act as they do because they don’t grant any moral relevance to other people’s lives, dreams or desires, and because they believe the world exists for them to take what they wish from it.

Not coincidentally, this is also a perfect description of a Randian protagonist. Remember, in our first impression of Howard Roark, we were told that he was so magnificently indifferent to the existence of others that he doesn’t even perceive them on the street. Other characters say of him that he’d walk over corpses to do what he wants, and apparently we should treat this as praise.

If crime and violence exemplify the evil second-hander mentality, how are we to understand characters like Atlas Shrugged‘s Ragnar Danneskjold, the heroic pirate who sabotages and destroys the socialists’ regime, sinks their ships and steals their cargo? And if it’s wrong to “force your personalities” on others through violence, how are we to excuse – spoiler alert! – the upcoming scene where Roark blows up a building he designed because it wasn’t built to his exact specifications?

I know, I know: the answer is that these acts of violence are acceptable because they’re “self-defense”, an infinitely elastic term that stretches to accommodate any crime which Rand’s protagonists commit. Like many things in the Objectivist worldview, it’s a term of art; just as “individualism” means liking the same things Ayn Rand liked and “reason” means coming to the same conclusions that Rand reached.

There’s just one way in which Roark and Wynand diverge:

Afterward, when Wynand had gone below to his cabin, Roark remained alone on deck. He stood at the rail, staring out at the ocean, at nothing.

He thought: I haven’t mentioned to him the worst second-hander of all — the man who goes after power.

As I’ve mentioned before, this is Gail Wynand’s fatal flaw and the only thing that makes him less than a perfect Objectivist hero. He seeks power because he wants to dominate others, whereas the perfect man has no desire for that and only wants the freedom to do his own work in his own way.

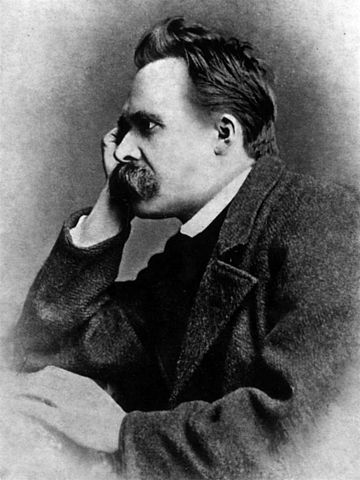

That said, this tenet of Rand’s philosophy sits uneasily beside her Nietzschean assertion that the vast majority of humankind is an ignorant rabble who don’t know what’s good for them, who have no real wishes or desires of their own, and and who instinctively despise greatness whenever they encounter it (as Roark said above about the “insidious kind of hatred” ordinary people feel for True Creators).

If you take this bleak premise as given, you have to admit it does seem reasonable for the rare individualist heroes to subjugate the masses, both for their own good and so they can’t persecute the geniuses as they otherwise would.

How else are the True Creators supposed to preserve their all-important freedom, when they’re a tiny, outnumbered minority in a hostile world? You can’t act as if other people are irrelevant when they might be coming for you with torches and pitchforks! By Rand’s own lights, couldn’t you conclude that Roark is the naive one, and Wynand is just doing what he has to to ensure the survival of great men?

Image credit: Wikimedia Commons

Other posts in this series: