The Fountainhead, part 4, chapter 12

At the start of this chapter, Roark returns to New York City. He’s been away on Gail Wynand’s yacht for three months (!), just the two of them alone together on the sea. (How on earth did they pass the time? If they didn’t have sex, that must have been a lot of monologues where they agreed with each other about capitalism.)

Back at the office, Roark accepts handshakes and greetings from his faithful employees. But when he picks up a newspaper, it stops him cold:

In the afternoon, alone at his desk, he opened a newspaper. He had not seen a newspaper for three months. He noticed an item about the construction of Cortlandt Homes. He saw the line: “Peter Keating, architect. Gordon L. Prescott and Augustus Webb, associate designers.” He sat very still.

That evening, he goes to see the site of Cortlandt Homes for himself. The first building is ready, but it’s not what he designed:

The building had the skeleton of what Roark had designed, with the remnants of ten different breeds piled on the lovely symmetry of the bones. He saw the economy of plan preserved, but the expense of incomprehensible features added; the variety of modeled masses gone, replaced by the monotony of brutish cubes; a new wing added, with a vaulted roof, bulging out of a wall like a tumor, containing a gymnasium; strings of balconies added, made of metal stripes painted a violent blue; corner windows without purpose; an angle cut off for a useless door, with a round metal awning supported by a pole, like a haberdashery in the Broadway district…

Roark’s design was altered by two of Ellsworth Toohey’s flunkies. Toohey got them added to the project using his political connections, and they proceeded to make one senseless change after another. They added balconies because they thought the tenants of Cortlandt would enjoy the fresh air, just like they used to enjoy sitting on fire escapes. A social worker angling for a job as “director of recreation” demanded they add the gymnasium for tenants’ use, and they obliged her; and so on.

The sole condition that Roark demanded of Peter Keating, in exchange for coming up with the design and letting Peter put his name on it, was that Cortlandt be built exactly as he designed it. Peter tried to hold up his end of the bargain, but he was beaten at every turn:

Keating fought. It was the kind of battle he had never entered, but he tried everything possible to him, to the honest limit of his exhausted strength. He went from office to office, arguing, threatening, pleading. But he had no influence, while his associate designers seemed to control an underground river with interlocking tributaries. The officials shrugged and referred him to someone else. No one cared about an issue of esthetics. “What’s the difference?” “It doesn’t come out of your pocket, does it?” “Who are you to have it all your way? Let the boys contribute something.”

…When Keating invoked his contract, he was told: “All right, go ahead, try to sue the government. Try it.” At times, he felt a desire to kill. There was no one to kill. Had he been granted the privilege, he could not have chosen a victim. Nobody was responsible. There was no purpose and no cause. It had just happened.

Ayn Rand takes it for granted that these changes desecrated Roark’s design for Cortlandt Homes, just as his Temple of the Human Spirit was desecrated when it was turned into a care home. But wait a minute.

Prescott and Webb made these changes because they believed, apparently sincerely, that they would improve Cortlandt Homes and make it more pleasant for the people who were going to live there. Were they right? That is, would these amenities genuinely have added to the enjoyment and appreciation of Cortlandt’s future tenants? Do they get any voice in choosing the place where they’d like to live?

We never find out, because it’s not a question Rand is interested in asking. As far as she’s concerned, her hero’s wishes are the only ones that are relevant. (The closest she comes is with her impossible pair of assertions that Roark is both incapable of understanding people and also that he designs buildings which are perfectly suited to the people who want to live in them.)

Instead, she denounces the changes on aesthetic grounds alone, using slanted and highly emotive language: “brutish cubes”, “bulging like a tumor”, “violent blue”, and so on. But, you know, two can play this game. Couldn’t one of Roark’s critics say that his original design was jagged and forbidding, like a field of thorns; or brutal and barren of human comfort, like a scorching desert; or gaunt and angular, like the hollow face and stretched flesh of a famine victim?

No one says anything like this in The Fountainhead. As with Hank Rearden’s trial in Atlas Shrugged, Rand doesn’t let both sides of the argument be heard, because then readers might find themselves agreeing with the “wrong” side. Instead, she proceeds from the premise that there’s only one objectively correct aesthetic, which is hers, and all other design styles can be evaluated and graded by how far they depart from it.

That night, Peter comes to Roark’s apartment to confess what happened. He offers to make a public statement, which Roark refuses:

Roark shook his head.

“Whatever I do, it won’t be to hurt you, Peter. I’m guilty, too. We both are.”

“You’re guilty?”

“It’s I who’ve destroyed you, Peter. From the beginning. By helping you. There are matters in which one must not ask for help nor give it. I shouldn’t have done your projects at Stanton. I shouldn’t have done the Cosmo-Slotnick Building. Nor Cortlandt. I loaded you with more than you could carry. It’s like an electric current too strong for the circuit. It blows the fuse. Now we’ll both pay for it. It will be hard on you, but it will be harder on me.”

At last, Rand admits that Roark, her supposedly flawless hero, has been acting unethically all along. But his crime isn’t that he helped Peter cheat on his assignments or win awards he didn’t deserve – the text doesn’t care about that. Instead, it’s that Roark’s designs were so good that merely being the conduit for them burned out Peter’s soul and sense of self-worth.

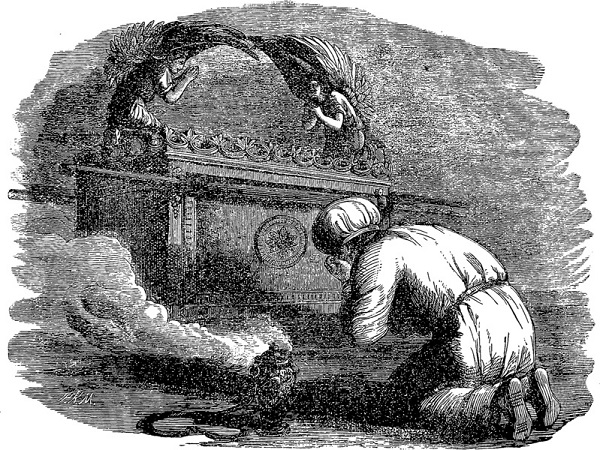

Apparently, Roark should have known better than to let the burning force of his genius come in contact with a lesser human’s body. This is like the Objectivist version of the Bible story where a man grabs the Ark of the Covenant to stop it from falling off a cart, and God strikes him dead on the spot. (I’m surprised that Roark doesn’t expect other people to take off their shoes in his presence.)

In Rand’s topsy-turvy worldview, it harms people to help them. Just sit and think about that for a minute. This is the most creative explanation yet for why her ubermensch heroes are unmoved by the plight of ordinary people starving in the gutter. It’s not that they don’t care, you see – it’s that they’re so much better than us that, even if they tried to help, they know that merely to touch lesser mortals like us would melt our faces off.

Image credit: Wikimedia Commons

Other posts in this series: