The Fountainhead, part 4, chapter 13

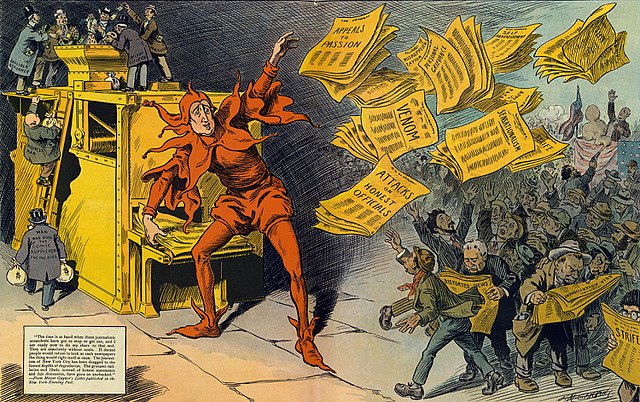

There’s a tidal wave of outrage against Howard Roark for blowing up the Cortlandt housing project. He has just one friend who’s willing to speak up in his defense. However, that friend owns a media empire:

Gail Wynand laughed. Resistance fed him and made him stronger. This was a war, and he had not engaged in a real war for years, not since the time when he laid the foundations of his empire amid cries of protest from the whole profession. He was granted the impossible, the dream of every man: the chance and intensity of youth, to be used with the wisdom of experience. A new beginning and a climax, together. I have waited and lived, he thought, for this.

His twenty-two newspapers, his magazines, his newsreels were given the order: Defend Roark. Sell Roark to the public. Stem the lynching.

I’ve observed that Ayn Rand was oblivious to the role of race in American history. The way she refers to the outcry against her white hero as a “lynching” is a particularly wince-worthy example.

Actual lynchings were a terror tactic used by a white supremacist society against people of color who violated the unwritten rules of racial hierarchy – by engaging in interracial relationships, demanding their human rights, or simply being too successful. The victims were dragged from their homes by angry mobs, beaten, tortured and brutally murdered. Usually, the mutilated body was left on display to terrify anyone else who might have thoughts about stepping out of their place.

Howard Roark has faced none of this. He was arrested by an officer of the law, allowed to go free on bail, and is living peacefully while awaiting trial. The only basis for this offensive comparison is the freeze-peach mentality that having to endure any sort of criticism or public rejection is equivalent to extrajudicial murder.

“In the filthy howling now going on all around us,” said an editorial in the Banner, signed “Gail Wynand” in big letters, “nobody seems to remember that Howard Roark surrendered himself of his own free will. If he blew up that building — did he have to remain at the scene to be arrested? But we don’t wait to discover his reasons. We have convicted him without a hearing. We want him to be guilty.”

Wynand is convinced that the public has judged Roark guilty without bothering to wait for the trial. There’s just one problem with this, namely that Roark actually is guilty, and Wynand knows it! If he’s trying to create doubt by suggesting that the real culprit wouldn’t have waited around to be arrested, this is a deliberately deceptive argument.

What’s the Objectivist position on lying and dishonesty? In Atlas Shrugged, John Galt denounces people who engage in “faking reality“, and a different section of the book claims that “There are no white lies, there is only the blackness of destruction, and a white lie is the blackest of all.” But like Rand’s supposed prohibition on initiating force, this seems to be a standard that only applies to her villains, not her heroes.

Wynand continues:

“Any illiterate maniac, any worthless moron who commits some revolting murder, gets shrieks of sympathy from us and marshals an army of humanitarian defenders. But a man of genius is guilty by definition. Granted that it is vicious injustice to condemn a man simply because he is weak and small. To what level of depravity has a society descended when it condemns a man simply because he is strong and great? Such, however, is the whole moral atmosphere of our century — the century of the second-rater.”

“Simply because he is strong and great”.

Notwithstanding what she herself wrote just one chapter previously, Ayn Rand has managed to convince herself that the public is out for Roark’s blood just because he’s so damn talented, not because he was caught red-handed at the scene of the crime. It bears not a little similarity to Rand’s real-life defense of the convicted killer William Hickman, another case where she glossed over the facts and convinced herself that the public hated someone because he was heroic and strong, rather than because of the brutal crimes he committed.

“Too little attention has been paid to the feminine angle of this case,” wrote Sally Brent in the New Frontiers. “The part played by Mrs. Gail Wynand is certainly highly dubious, to say the least. Isn’t it just the cutest coincidence that it was Mrs. Wynand who just so conveniently sent the watchman away at just the right time? And that her husband is now raising the roof to defend Mr. Roark? If we weren’t blinded by a stupid, senseless, old-fashioned sense of gallantry where a so-called beautiful woman is concerned, we wouldn’t allow that part of the case to be hushed up. If we weren’t overawed by Mrs. Wynand’s social position and the so-called prestige of her husband — who’s making an utter fool of himself — we’d ask a few question about the story that she almost lost her life in the disaster. How do we know she did? Doctors can be bought, just like anybody else, and Mr. Gail Wynand is an expert in such matters.”

It’s a surprise that Rand would permit one of her villains to write this, because again, Sally Brent is absolutely correct to accuse Dominique of being in on the plot. She’s wrong about Dominique faking her injuries, but she couldn’t have guessed that (if anything, the real story is even less plausible). But she’s right about everything else, including that Gail Wynand is an expert in deception and shouldn’t be trusted. Remember, he boasted to Dominique that he could’ve coached her to lie better!

It goes unremarked-upon by Ayn Rand that her villains are 100% correct about what they accuse the heroes of doing. This is something we also saw in Atlas Shrugged: she’s so reflexively on her heroes’ side, she gives the villains good and valid points to make, in the total confidence that it doesn’t matter because the protagonists are exempt from ordinary standards of morality and we’ll side with them anyway.

However, she does throw in one false accusation – not against Roark, but against Wynand:

“We have it from an unimpeachable source,” wrote a radical newspaper, “that Cortlandt was only the first step in a gigantic plot to blow up every housing project, every public power plant, post office and schoolhouse in the U.S.A. The conspiracy is headed by Gail Wynand — as we can see — and by other bloated capitalists of his kind, including some of our biggest moneybags.”

What a shockingly unfair accusation! Rand would never write a heroic character who secretly plotted to destroy everything built by the government… until her next book.

The Banner ran Roark’s biography, under the byline of a writer nobody had ever heard of; it was written by Gail Wynand. The Banner ran a series on famous trials in which innocent men had been convicted by the majority prejudice of the moment. The Banner ran articles on man martyred by society: Socrates, Galileo, Pasteur, the thinkers, the scientists, a long, heroic line — each a man who stood alone, the man who defied men.

I hate to belabor the point, but since Ayn Rand is trying to sweep her own plot under the rug, I guess I have to: Roark isn’t being accused because of “majority prejudice” – as in “The building blew up, let’s go find the greatest architect in New York and put him on trial for it!” – but because he was found standing over the detonator.

This echoes a similar subplot in Atlas Shrugged, where Hank Rearden is enraged by his wife suspecting him of cheating on her, even though he was cheating on her. In both novels, Rand considers it outrageous that her hero is accused of committing a crime he actually did commit. She didn’t view this as hypocrisy because she considered her protagonists exempt from the rules of morality that apply to lesser mortals.

Something else you may have noticed, but I’m not sure Rand did, is how bad Wynand’s defense of Roark is. Rather than trying to win over the people who believe Roark is guilty, he’s attacking them in the most alienating and insulting way possible. Basically, his defense is, “Why can’t you see that he’s innocent, you drooling morons?”

There’s an ironic accuracy to this chapter, in that Rand thought of herself as just like Gail Wynand: a lone hero bravely speaking the truth to an ignorant and hostile world. In fact, she was just like Gail Wynand: a strident ideologue who had no idea how to convince or persuade, who could only declare her own opinions as dogmatic truth and issue insults and denunciations of anyone who didn’t see things the same way she did.

I’m guessing Ayn Rand wouldn’t have seen the problem with defending your character this way, either. (NSFW!)

In spite of this, I think we’re supposed to believe that Gail Wynand’s strategy would have worked, except that Ellsworth Toohey had too much time to brainwash the public. The text says, “The ground had been prepared, the pillars eaten through long ago.”

And when one of Wynand’s employees frets about why the backlash against Roark is so ferocious compared to other criminals they’ve covered, Toohey gloats that there are occasions “when the issues at stake are not the ostensible facts at all” – implying that people don’t genuinely care about the destruction of a housing project, they’re just furious at him because he exerted his will in defiance of the majority.

This goes to show that, in Ayn Rand’s worldview, no one is honestly mistaken about what they’re doing. The bad guys aren’t bad because they have different priorities, but because they’re making a conscious choice to be evil and want to crush anyone who won’t conform. And in The Fountainhead, that bad-guy category includes nearly all of humanity. The way she sees it, her heroes are basically the protagonists of a zombie movie: up against a mindless horde that can’t be reasoned with.

Image credit: Wikimedia Commons

Other posts in this series: