The Fountainhead, part 4, chapter 15

Returning to New York from a business trip, Gail Wynand opens a copy of the New York Banner. To his astonishment, Ellsworth Toohey’s column is about Roark and the upcoming trial:

“In the person of Howard Roark, we must crush the forces of selfishness and antisocial individualism — the curse of our modern world — here shown to us in ultimate consequences. As mentioned at the beginning of this column, the district attorney now has in his possession a piece of evidence — we cannot disclose its nature at this moment — which proves conclusively that Roark is guilty. We, the people, shall now demand justice.”

Wynand had ordered Toohey not to write about Roark, but not only did Toohey disobey him, he somehow got it into print under Wynand’s nose.

In a fury, Wynand storms into his headquarters. His editor-in-chief Alvah Scarret is grovelingly apologetic, explaining that he was out sick and a traitorous copy editor had Toohey’s column printed despite Wynand’s standing orders:

“Who was on the copy desk?”

“It … it went through Allen and Falk.”

“Fire Harding, Allen, Falk and Toohey. Buy off Harding’s contract. But not Toohey’s. Have them all out of the building in fifteen minutes.”

(An aside: Remember the good old days when workers had contracts?)

Wynand orders all copies that have already hit the streets to be recalled. He sits at his desk and pens a furious editorial denouncing Toohey (“I am still holding on to a respect for my fellow men sufficient to let me say that Ellsworth Toohey cannot be a menace”) and asking his readers’ forgiveness for employing him. But while he’s writing it, Toohey himself walks in the door:

“I came to take my leave of absence, Mr. Wynand,” said Toohey. His face was composed; it expressed no gloating; the face of an artist who knew that overdoing was defeat and achieved the supreme of offensiveness by remaining normal. “And to tell you that I’ll be back. On this job, on this column, in this building. In the interval you will have seen the nature of the mistake you’ve made… So you were a possessive man, Mr. Wynand, and you loved your sense of property? Did you ever stop to think what it rested upon? Did you stop to secure the foundations? No, because you were a practical man. Practical men deal in bank accounts, real estate, advertising contracts and gilt-edged securities… and leave us such trivia as the theater, the movies, the radio, the schools, the book reviews and the criticism of architecture. Just a sop to keep us quiet if we care to waste our time playing with the inconsequentials of life, while you’re making money. Money is power. Is it, Mr. Wynand? So you were after power, Mr. Wynand? Power over men? You poor amateur!”

What’s truly remarkable about this passage is that, despite putting this moral in the mouth of her villain in her own book, despite explicitly spelling it out, this is a lesson that Ayn Rand herself never learned.

In Atlas Shrugged, her heroes make the exact same mistake that Gail Wynand does. They never try to defend themselves or justify their actions. They have no advertising campaigns, no marketing, no PR departments. They focus on making money and cede the marketplace of ideas entirely to their ideological enemies. And then they’re startled and angry when the public doesn’t side with them.

Rand’s distaste for the concept of persuading people, her belief that powerful capitalists should simply be able to make decrees and be obeyed, is one thing that is consistent across her books. The lesson she appears to have taken away from her own plot isn’t “It’s a bad idea to concede the debate without making an argument,” but rather, “If the public doesn’t immediately fall in line behind you without you even trying to convince them, they’re even more evil than you thought, and it’s right and just to exterminate them.”

Wynand makes a further unpleasant discovery: while he wasn’t paying attention, Toohey’s minions have infiltrated every corner of his media empire. As soon as Toohey is fired, the rest of the paper’s employees go on strike in solidarity:

Wynand had never given a thought to the Union. He paid higher wages than any other publisher and no economic demands had ever been made upon him. If his employees wished to amuse themselves by listening to speeches, he saw no reason to worry about it. Dominique had tried to warn him once: “Gail, if people want to organize for wages, hours or practical demands, it’s their proper right. But when there’s no tangible purpose, you’d better watch closely.”

…The strikers presented two demands: the reinstatement of the four men who had been discharged; a reversal of the Banner’s stand on the Cortlandt case.

This is yet another jaw-dropping statement by a Randian protagonist: Dominique says it’s the “proper right” of laborers to organize and bargain collectively for higher pay, shorter hours or better working conditions.

This goes well beyond Rand’s earlier neutrality on labor unions. It’s a positive endorsement.

Rand apparently took this stance because of her childlike naivete in the belief that abolishing all labor regulations would be good for workers. She really believed that their ruthlessly selfish capitalist bosses, if unconstrained by government or law, would pay their employees well and treat them respectfully. Needless to say, she did a sharp swerve on this. By the time she wrote Atlas, her heroes were good capitalist union-busters as you’d expect.

While his workers picket on the sidewalk outside and his circulation plummets, Gail Wynand resorts to hiring scabs to keep his business running:

He tried to hire new men. He offered extravagant salaries. The people he wanted refused to work for him. A few men answered his call, and he wished they hadn’t, though he hired them. They were men who had not been employed by a reputable newspaper for ten years… They were drunk most of the time. Some acted as if they were granting Wynand a favor. “Don’t you get huffy, Gail, old boy,” said one — and was tossed bodily down two flights of stairs. He broke an ankle and sat on the bottom landing, looking up at Wynand with an air of complete astonishment.

It just wouldn’t be an Ayn Rand book without one of her protagonists heroically throwing someone down the stairs, would it?

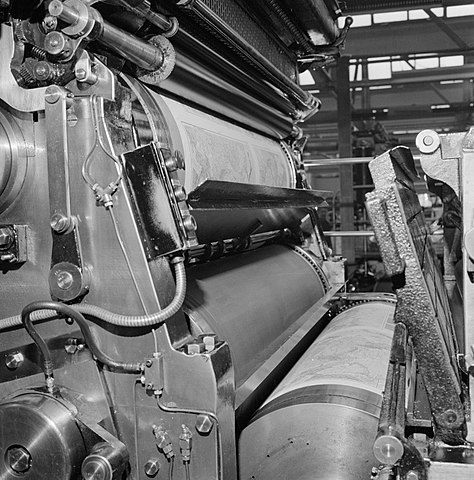

There were policemen outside, and in the halls of the building. It helped, but not much. One night acid was thrown at the main entrance. It burned the big plate glass of the ground floor windows and left leprous spots on the walls. Sand in the bearings stopped one of the presses. An obscure delicatessen owner got his shop smashed for advertising in the Banner. A great many small advertisers withdrew. Wynand delivery trucks were wrecked. One driver was killed. The striking Union of Wynand Employees issued a protest against acts of violence; the Union had not instigated them; most of its members did not know who had. The New Frontiers said something about regrettable excesses, but ascribed them to “spontaneous outbursts of justifiable popular anger.”

Obviously, Rand expects us to treat it as an outrage that union thugs are trying to intimidate Wynand through acts of violence. However, she told us in the immediately preceding passage about an equally violent act that Wynand commits against one of his own employees, and apparently she expects us to treat it as excusable. Was that also a “spontaneous outburst of justifiable anger”? Why is it OK when a capitalist does it?

Image credit: Willem van de Poll via Wikimedia Commons

Other posts in this series: